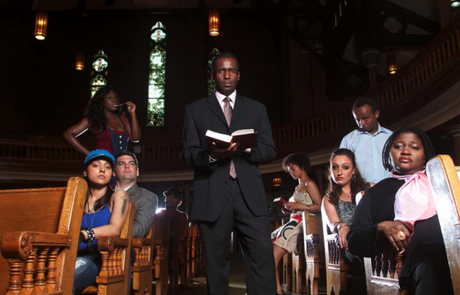

Photo from expect.org/awake. Credit: Steve Carty

“Cain!” roared the pastor, his voice thundering throughout the church.

“Where is your brother?”

The audience shuffled. The pews creaked. We all knew Cain had murdered Abel — but in that moment, not even God could force a confession.

“I don’t know,” came the flippant reply. “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

The words ignited something in me that they never have before. I’ve listened to the story of Cain and Abel many times but yesterday, in the context of a eulogy, I heard it.

This despite the fact that the whole funeral was staged. The sermon was the backbone of a play called AWAKE, which premiered at the Toronto Fringe Festival this year. The audience had gathered to mourn the loss of all of the young men who have fallen to gang violence, especially in St. Jamestown and Rexdale.

The playwrights call it “docu-theatre” – The eulogy had originally been delivered at the real funeral of 19-year-old Justin Shephard. The script was made up of verbatim excerpts from actual interviews with community members: mourning mothers, shaken friends, hardened police officers, youth from “at-risk” communities. People like me.

The altar was a stage for gospel, dance hall, spoken word, flashing lights, and a symbolic casket.

Nadia Beckles, played by Beryl Bain, spoke of her son Amon. In 2005, the 18-year-old was gunned down at a funeral for his best friend. After the shooting, his mother ran out of the church and knelt by him, covering his wounds with her hands.

Then, in one of the most poignant moments of the play, she looks up in disbelief as police arrive and ask attendees if they know the victim.

She watches his friends turn away. They say they don’t know Amon.

Where is your brother?

The Silence

A group of young men in the audience talked throughout the entire play, and I smiled to myself. Some people may have thought they were rude — and maybe they were — but their presence made me feel like I was home in Rexdale. To understand why, you only have to ride the Finch bus after the school bell rings, try to find a quiet corner at Albion library, or watch a movie at Rainbow in Woodbine mall. The buzz is everywhere.

Peyson Rock. Credit: Steve Carty

When the silence happens, it’s deafening. Something is usually wrong.

It’s the code, says Lauren Brotman on stage.

As “Smokey,” she recalls the number of stitches she needed on her face after her ex beat her up (six, no … seven). She was furious, but didn’t snitch. There are many complicated reasons for this, too many to list here, but the code is why Amon’s friends turned away. It’s why, as a reporter, I am used to writing “no witnesses have come forward” or “police say residents have been uncooperative.”

On stage, the pastor looks into the light.

“We are not all evil. We are not all guilty — but we are all responsible.”

The Story

To get to the story, playwrights Laura Mullin and Chris Tolley had to crack the code. They had to tap into that small part of every witness that feels responsible.

The pair stood, a bit shy, during the Q & A after the play. A man asked them why they’d been moved to write the piece. They started by admitting they were not from ”at risk” neighbourhoods as the man let out a knowing laugh.

Their answer, if I make take allowances, is that they wanted to see if that silence could be broken, like bread among family, and shared.

“It was hard to get people to start talking, but once they did, they couldn’t stop,” said Mullin.

But after so many in-depth interviews, how were they supposed to make characters, and not caricatures? Which threads were they to cut? St. Jamestown, Rexdale … these neighbourhoods are the definition of diversity. How could they do them justice?

Tolley spoke of a living room blanketed in interview transcriptions, of cultures within cultures they simply could not fit in. They couldn’t include immigration stories and other important neighbourhood nuances. Because I know Rexdale, and because I know reporting, I can appreciate the difficulty of their work.

But in the end, I believe they created something worth seeing.

They managed to tell a story that outsiders could appreciate and insiders could recognize — like bridging the gap between Jane Creba and Justin Shephard for an audience that could be coming from either side.

The Sincerity

At first, I cringed at the pastor’s words. They seemed theatrical, contrived — which would have made sense if they were written for the purposes of the play.

But then I looked at my church-going mother, who sat beside me in the dark church, and noticed that her eyes were sparkling.

He was preaching to his choir.

At one point, I tuned into conversation of the young men that wouldn’t shut up. They laughed when Knowledge (played by Peyson Rock), entered the room with his back to the wall. At all times, he explained, he needs to know exactly who is behind him.

At that, one guy blurted out: “truth.”

The play, I realized, is made up of many languages and no one speaks all of them fluently. Each actor, like each person, performed many roles — sometimes roles as disconnected as your street name and your given name. It’s up to us to make the connections.

If you’re in Toronto, I recommend you catch this play before the end of the Fringe Festival — especially if you feel nothing when you hear of these deaths.

Then go home and ask yourself: Where is your brother?

AWAKE, at the Toronto Fringe Festival

July 6-10 and 12 – 17

8:00 p.m. every night.

The Walmer Baptist Church

88 Lowther Avenue

Door: $11

Advance $10

Advance Ticket Sales: (416) 966-1062

or www.fringetoronto.com