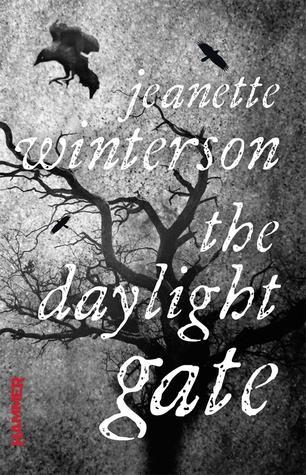

The Daylight Gate, by Jeanette Winterson

THE NORTH IS the dark place.

Hammer Films used to be a British institution. From the late 1950s through to the 1970s it produced a wide range of independent British horror cinema, much of it very good. These films were made quickly and generally on a very low budget. Many were utterly forgettable, but some were absolute classics fondly remembered to this day.

Recently Hammer has had something of a revival. The brand was bought out back in 2007 and the new owners are putting out fresh horror cinema under that label (including the excellent low key British horror movie Wake Wood, which is in the best traditions of Hammer). They’ve also launched a publishing arm, which has put out horror titles by existing horror writers and in some cases by more literary writers spreading their (presumably dark) wings.

I’m a Hammer horror fan and a Jeanette Winterson fan, so when Hammer published her The Daylight Gate they pretty much had me in mind. Applying literary fiction techniques to genre though can easily come unstuck. Some writers (and readers) assume that genre is a lesser form of writing than literary fiction, the beetle-browed Neanderthal to literary fiction’s elegant Cro-Magnon. The truth of course is that genre is simply writing within a particular tradition with particular goals. Even so, if you don’t understand the tradition, or worse yet talk down to it, you can easily write a book which literary fans will dislike because it has genre elements and which genre fans will dislike because those genre elements aren’t very good.

Jeanette Winterson though isn’t a writer who has much truck with the concept of genre, or literary categories generally. As she said in the context of her Stone Gods: “I can’t see the point of labelling a book like a pre-packed supermarket meal. There are books worth reading and books not worth reading. That’s all.” So, is The Daylight Gate worth reading?

Yes, it is (I can’t be bothered with cliffhangers within a blog, they seem so self-important).

THE PEDLAR JOHN Law was taking a short cut through that nick of Pendle Forest they call Boggart’s Hole. The afternoon was too warm for the time of year and he was hot in his winter clothes. He had to hurry. Already the light was thinning. Soon it would be dusk; the liminal hour – the Daylight Gate. He did not want to step through the light into whatever lay beyond the light.

John Law runs into some women of the Demdike clan on his journey. One asks him for some pins, and when he refuses shouts curses at him. he flees, collapses in a nearby inn where he promptly has a stroke uttering but one word, “Demdike”.

That incident, some mocking women and the collapse of an unhealthy man unwisely running through the dusk, leads to one of the most famous witch-trials in English history. The year is 1612 and the King, James 1st of England, is famously obsessed with witches. The book is fiction, but what it’s based on is real. There was a peddler by name John Law. Two women of the Demdike family did ask him for pins, he did collapse and they were later blamed. It ended in ten executions, nine women and one man. It was a pointless act of judicial barbarity, now part of England’s tourist trail.

The characters then in this novel are fictional, but not entirely so. There was a magistrate by name Roger Nowell who acted as prosecutor. There was a court clerk named Thomas Potts who wrote a detailed account of the trial that did wonders for his later career. There was an accused known commonly as mould-heels, and there was an Alice Nutter.

Alice Nutter was unusual among the accused. Where most of the supposed witches were uneducated and desperately poor, Alice Nutter was a wealthy widow. Her links to the other accused were slight, although there’s some evidence that she may have been a crypto-Catholic. Looking back all these centuries later she stands out as an oddity. It’s Alice Nutter therefore that Winterson chooses as the protagonist of her version of these terrible events.

Here Alice Nutter is that most dangerous of things, much more perilous than a witch, she’s a woman independent of the need for men. She has her own fortune made from a royal warrant granted to her by Queen Elizabeth for a magenta dye so deep and rich that none can understand how she makes it. She studied under John Dee, and her appearance belies her years for she perpetuates her youth with a lotion of Dee’s devising.

Is then Alice Nutter a witch? It’s hard to say. Her dye is a question of clever chemistry. Dee is part of the historical record so his presence proves nothing. The lotion could just be an early form of moisturiser, an unusually effective one now lost.

Alice herself is ambiguous in her beliefs about witchcraft. For her the other accused are immiserated, and so desperate for any form of power or control in their lives that they’ll take it even from a Dark Man who may or may not exist. The real crime here isn’t witchcraft, it’s oppression.

“‘Popery witchery, witchery popery’” cries Thomas Potts, “a proud little cockerel of a man; all feathers and no fight.” As the machinery of justice cranks into life it pulls in a wider circle of people. The desperate settle debts through accusations, hoping to help themselves by hurting others or at least to settle a few scores on their way down:

‘I will testify against them all.’ Constable Hargreaves refilled the tankards. ‘And what of Mistress Nutter?’ Jem took his beer and drained it off. ‘I will say to Magistrate Nowell that she promised to lead us and to blow up the gaol at Lancaster and free Old Demdike.’ He started to laugh – high, hysterical. They were laughing with him. He wasn’t alone and outside any more. Not cold or hungry or afraid. He would be safe now.

Alice Nutter believes herself above all this, protected by her wealth and position, and of course by her relative innocence. That’s unwise. She’s bisexual, tending towards a preference for women (this is a Winterson novel after all). She engages with men as equals, enjoys conversation with Roger Nowell who likes her but is all too aware that if he doesn’t comply with her prosecution his own reluctance could land him in the dock right next to her.

So, an intelligent woman able to see the contradictions of the society around her and unable to hide her own separation from it. Put that way it could be a description of Winterson’s first novel, Oranges are not the Only Fruit. It’s easy to see why Winterson found this story interesting, why she thought there was a book inside it. This isn’t though a historical novel (Winterson doesn’t write those), it’s a horror novel.

The horror here isn’t simply supernatural. This book includes graphic scenes of child abuse, rape, torture and relentless human degradation. This is a novel where two of the accused are slightly better off than the others because they’re young enough for their jailor to want to rape them, and so to let them out of the communal cell for a little while and to wash before he sets to. That’s horror, perhaps too much so. The horror genre is generally a comforting one because it’s terrors aren’t real, but there’s nothing reassuring in unjust imprisonment, brutality and sexual exploitation.

There are scenes too of witchcraft – because most of the accused here believe themselves to be witches, whether they really are or not. One particularly grisly sequence involves an attempt to animate a skull by sewing a dismembered tongue into it so as to summon imagined supernatural aid. In the main there’s no evidence it works, but Alice Nutter is again an exception. It’s not clear cut, but there’s some suggestion that during her time with Dee she may have been involved with matters beyond this world, and that this may be part of her present undoing.

‘Elizabeth has betrayed you. She sold her Soul to enjoy her wealth and power for a fixed time. Now, unless there is a substitute for her Soul, she will lose everything. You are the substitute.’ ‘I do not believe in those things.’ ‘It does not matter what you believe. Believe what is.’

If ever there were a writer comfortable with ambiguity it’s Winterson. Here the real and the unreal meet, but the unreal is a manifestation of the real. Some of the witchcraft is plainly superstition, but it’s uncertain if it all is. If magic exists though its expression is merely a reflection of wider social forces. Witchcraft is attractive because women born without power have few other options. Alice is dangerous not because she doesn’t grow old as other women do but because she thinks for herself. For once the old cliche is true, it doesn’t matter whether what the characters believe is real, all that matters is that they believe it’s real.

The book’s not without problems. There are inherent tensions in depicting real life horror and the supernatural in the same work, and as noted above it’s hard to care about the machinations of the Black Man when you’ve been reading about a serial child abuser a few pages previously. Possible horror, well written, makes it hard to care about impossible horror.

Winterson also overdoes some motifs, particularly the phrase “the daylight gate” which is frankly overused and so becomes rather tedious and the meanings of which are exhaustively spelled out for the reader. There’s a sense too that Winterson just plain crowds too much in, with John Dee entering the tale, and an encounter with Shakespeare, plus a wandering emasculated Jesuit priest (it’s telling that Alice Nutter’s only male romantic interest doesn’t have a penis). For a fairly short novel it’s dense to the point of overflowing, and it’s not as if the trial itself hasn’t already got a rich cast of characters and incident. The book doesn’t need to feel as if everyone of any note in Jacobean Britain is wandering through its pages.

It’s not then an unqualified success. Winterson is combining two forms that don’t easily sit together, and the results don’t always gel. She avoids though the main traps of this sort of exercise, she doesn’t patronise the genre, she doesn’t give the impression she thinks she’s slumming it, the concerns she explores here are concerns she’s explored before in other works and that genuinely interest her.

Ultimately it’s what it says on the cover – a Jeanette Winterson novel. It’s not her best and it’s probably not for those of her fans who don’t also like the odd slice of the macabre, but if like me you’re the target audience for a Jeanette Winterson Hammer horror novel then that’s precisely what this is. Like the Hammer classics of the 1970s it sometimes doesn’t quite convince, and sometimes you can see how the effects work, but for all that it’s still well made and a lot of fun.

Recent evidence by the way points to the Neanderthals being as intelligent and sophisticated as we are, which makes the analogy I used early on in this piece very unfair to Neanderthals. Sorry Neanderthals, and sorry about that whole driving you extinct thing too. Mistakes were made. As a final aside also I can’t write this review and not mention the (utterly unconnected save for subject matter) album 1612 Underture by the Eccentronic Research Council with Maxine Peake – easily the best electronic music feminist satire on the treatment of the Pendle witches out there.

Filed under: Horror Fiction, Winterson, Jeanette Tagged: Hammer Films, Jeanette Winterson, Pendle Witches