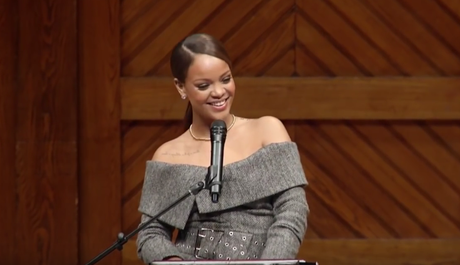

Rihanna accepting her award

On February 28, 2017, Rihanna walked up the creaky wooden steps of one of Cambridge’s storied halls to accept the Harvard Foundation’s 2017 Peter J. Gomes Humanitarian of the Year Award. While she is best known for her music, Rihanna was recognized that day for her less publicized humanitarian work—including her investment in a modernized oncology wing at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in her hometown of Bridgetown, Barbados, and establishing scholarships to support Caribbean students who want to attend college abroad, among other philanthropic efforts.

While accepting the honor, Rihanna made an impassioned plea for more people to become involved in humanitarian work for a simple reason: We should always strive to be in better service of others. While addressing an audience at one of the most selective, renowned schools in the world, the recipient boldly stated that one does not have to be immensely wealthy or hypereducated to engage in humanitarianism.

With all due respect to Rihanna, whose talent and willingness to give I fervently admire, I would have to disagree. Unfortunately, a foray into humanitarianism requires more than just the desire to help. The difference between supporting and believing in humanitarian work and actually engaging in it is that the latter requires significant financial investments that are not accessible to everyone.

In her acceptance speech, Rihanna recounted seeing a commercial that asked viewers to give small sums of money to support disadvantaged children in Africa. This was the first interaction that she had with the world of humanitarian work, she said, and it inspired her to engage in that kind of work as soon as she had the financial means to do so. I (probably along with many other viewers of her speech) could practically hear sad tunes along the lines of Sarah McLachlan croon in the background as she spoke; commercials beseeching viewers for funds for a variety of causes were omnipresent throughout my childhood. This brand of philanthropy—a large-scale, well-funded effort designed to have broad-reaching impact—is both the kind of humanitarian work with which we often see celebrities associate and, it seems, the kind that an organization like the Harvard Foundation is likely to recognize.

But approaching humanitarianism as soliciting money from major donors, who may see their donations as investments rather than gifts, is not always effective. What’s more, this approach, which seems particularly common in Western society, typically views foreign countries’ political and social values and realities as a uniform “other” in relation to themselves; there is little consideration for each country’s independent identity. This oversimplification of non-Western countries’ issues, as well as the perpetuation of the Western “savior” complex and lack of consultation with communities about their own issues, fit all too well into an established legacy of colonial infantilization of “non-progressed” countries.

One notable example of this dynamic is that of the Deworm the World initiative. This initiative raised money for the provision of deworming pills to students in “underdeveloped” countries based on a 2004 study that showed that administering these pills to 30,000 Kenyan students improved their educational outcomes. The project expanded to India, Ethiopia, and Vietnam after receiving widespread support from international organizations and corporations—but failed to commission regionally specific studies of whether the relationship between hookworm elimination and education stretched beyond the community at the center of the original study. Despite research into deworming pills not turning up any negative effects of this treatment, the issue at hand is about the proper allocation of funds towards projects that have a substantial impact on local communities. Deworm the World—now a subsection of the NGO Evidence Action—is said to have administered these pills to 17 million Indian people without any follow-up measure of test scores, school attendance, or graduation rates. The kind of internationally accrued funding collected for this project may be hemorrhaged on a program that has no further impact beyond its original mission.

The cruel irony of humanitarian work is that both money and time are necessary for any initiative to succeed, but it’s often impossible for such efforts to access both in practice. Community organizers who engage in this kind of activism are often already marginalized themselves, since many become motivated to address issues because they are plaguing their own communities. Community organizing is also not the most lucrative career—the current median starting salary is around $35,000. What’s more, the lack of state investment in social justice-oriented programs often either leaves them underfunded or results in their funds being allocated to overworked and overburdened administrators. Yet, while individual organizers as well as the organizations they work for need money, simply donating money to a cause is not a sustainable or systemic solution either. While money is (unfortunately) necessary to fight injustice, truly trying to remedy a systemic problem also requires an investment of time in the form of grant writing, calling political representatives, event organizing, canvassing, and more.

The result is a humanitarian “industry” that attracts many qualified candidates but can only support a few underpaid (or unpaid) internships and entry-level positions. These sparse opportunities then also often go to those who had the socioeconomic privilege to be groomed for this kind of career in the form of postgraduate degrees or the ability to take unpaid internships and still support themselves. This results in a space that continually excludes the very people from communities who have direct experience with many of these issues, ironically reproducing the kind of polarization of income and opportunity that humanitarian work is trying to bridge.

This brings us to the dire conclusion that marginalized people will only be able to contribute to humanitarian work should societal power be completely restructured and redistributed. Rihanna said it herself: As a child, she longed for the day that she could become wealthy and share that wealth with the people who needed it most. She also said, however, that she wished that she could tell that child that one doesn’t need an absurd amount of money to be humanitarian. Well, maybe you don’t need to expend a lot of money and/or effort to help your neighbor, but you definitely do to make substantial impact on a larger scale—to accomplish the kind of work the organizations Rihanna has partnered with do. The specific type of contribution she envisioned making—such as donating large sums of money to international organizations to be redistributed abroad—wouldn’t have been possible without her financial means, and she was not recognized by the Harvard Foundation for helping her neighbor.

I don’t doubt that Rihanna’s humanitarian work comes from a place of compassion and duty. I don’t want to devalue her work, especially since it is so difficult for women to acquire professional hyphens (such as designer-singer-philanthropist) and be taken seriously. I am not discrediting Rihanna’s contribution to Bridgetown’s administration of healthcare, to Caribbean college students or to other causes, but rather questioning how she chose to present her involvement in this work. It is important for her (and any other celebrity philanthropists) to address the unequal representations at upper levels of NGOs and transnational organizations, the lack of federal funding for community initiatives, and the ways in which efforts like the establishment of more grants and stipends for local social justice-oriented projects and expanding state support for these causes can help. Humanitarian work has its merits, but like anything worth fighting for, it remains flawed in practice. Without exercising critical inward inquiry, we will find ourselves repeating the Same Ol’ Mistakes.