Cross Posted from Orionmagazine.org

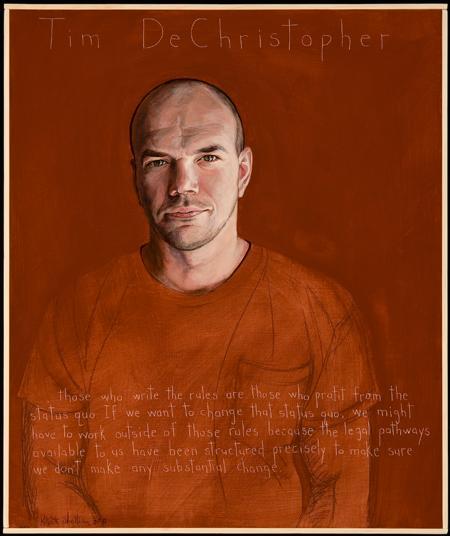

FROM THE MOMENT I HEARD about Bidder #70 raising his paddle inside a BLM auction to outbid oil and gas companies in the leasing of Utah’s public lands, I recognized Tim DeChristopher as a brave, creative citizen-activist. That was on December 19, 2008, in Salt Lake City. Since that moment, Tim has become a thoughtful, dynamic leader of his generation in the climate change movement. While many of us talk about the importance of democracy, Tim has put his body on the line and is now paying the consequences.

On March 2, 2011, Tim DeChristopher was found guilty on two felony charges for violation of the Federal Onshore Oil and Gas Leasing Reform Act and for making false statements. He refused to entertain any type of plea bargain. On July 26, 2011, he was sentenced to two years in a federal prison with a $10,000 fine, followed by three years of supervised probation. Minutes before receiving his sentence, Tim DeChristopher delivered an impassioned speech from the courtroom floor. At the end of the speech, he turned toward Judge Dee Benson, who presided over his trial, looked him in the eye, and said, “This is what love looks like.” Minutes later, he was placed in handcuffs and briskly taken away.

After several transfers from three states, he is now serving the remainder of his time in the Herlong Federal Correctional Institution in California. When I asked Tim about his thoughts concerning prison, he responded, “All these people are worrying about how to keep me out of prison, but I feel like the goal should be to get other people in prison. How do we get more people to join me?” In fact, thousands of citizens are following his lead and are choosing to commit acts of civil resistance in protest of mountaintop removal, the construction of the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline, and as participants in the ever-expanding Occupy Wall Street movement. They recognize that we can no longer look for leadership outside ourselves. And that if public opinion changes, government changes.

On May 28, 2011, Tim DeChristopher and I had a three-hour conversation in Telluride, Colorado, during the Mountainfilm Festival. We talked openly and candidly with one another as friends. No one else was in the room. We are pleased to share this conversation with the Orion community.

—TTW

TERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS: The first thing I want to say to you, Tim, is thank you. Thank you for what you’ve done for us, as an act of protest, as an act of imagination, and an act of true, civil resistance.

TIM DECHRISTOPHER: Well thank you.

TERRY: So let’s talk about your mother.

TIM: [Laughter.] Okay.

TERRY: You know, when I saw your mother, I had a better sense of who you are.

TIM: Why did you have a better sense of who I am?

TERRY: I watched her during the trial. And I imagined what it must be like for her, who loves you so much, who gave birth to you, who’s raised you—what that must have been like for her to have to sit there, not speak, you know, watch how political this was, watch your dignity, knowing what the consequences might be and, in fact, are going to be. And I never saw her waver. I mean the only person that I saw with as much composure in that courtroom as you was your mother. You couldn’t see her—she was sitting behind you—but she never wavered. Her spine was like steel.

TIM: Yeah. I think that’s definitely what I’ve gotten from her. I only have vague memories of when she was fighting the coal companies, when I was a little kid, in the early days of mountaintop removal—I don’t know if they were really my memories or stories that I’ve heard from the family. But I think a lot of my activism has been shaped by that. I remember hearing about when this coal miner stood up at this hearing and said, “My grandfather worked in the mine, my father worked in the mine, and I worked in the mine, and you people are telling us we can’t do this, and blah blah blah.” And my mom just fired right back and said, “And if you start blowing up these mountains, you will be the last generation that is ever a miner in West Virginia. You will kill the family tradition if you try to mine this way.”

TERRY: And how old were you?

TIM: I was really young. We moved away when I was eight.

TERRY: And so was this in the ’70s?

TIM: No, it was in the early ’80s.

TERRY: And you were born?

TIM: ’81.

TERRY: And what was the trigger point for your mother?

TIM: I don’t know. But then, as I got older, she got out of activism. She told me once that she pulled out of all the political stuff to focus on raising me and my sister. And I think that’s always been something that I carried with me. You know, that she had this role in the political sphere in our community, and she stepped out of that to put it into me. So I’ve always felt like I had somewhat of a greater responsibility to pull not just my own weight, but that extra weight that she put into me.

TERRY: And you were the oldest?

TIM: No, I’m the youngest. My sister’s two years older.

TERRY: And is it just the two of you?

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: And what town in West Virginia?

TIM: I was born in a town called Lost Creek. And then when I was really little we moved to West Milford.

TERRY: And has anyone in your family been in the coal industry?

TIM: My dad worked his whole career in the natural gas industry.

TERRY: So you and I have that in common.

TIM: Yep.

TERRY: In what venue? Was he laying pipe?

TIM: He was an engineer, involved in the transmission side of things. And then rose up and became a manager and an executive.

TERRY: And what would you say the ethos in your home was?

TIM: You mean like politically?

TERRY: Yeah, and spiritually. You know, if there was a DeChristopher credo . . . I mean, in our family I’d say it was “work.” That was my father’s credo. That was his religion. And so it became ours.

TIM: I’d say in my family it was “knowledge,” or “logic.” It was very intellectual.

TERRY: So a typical conversation around your dinner table would be?

TIM: Around political issues. Local issues. My parents definitely identified as liberals or progressives. And I think especially when I was younger, they were rather free-thinking. But then got comfortable. As I got older.

TERRY: How so?

TIM: They started making more money.

TERRY: And how did that impact you?

TIM: Well, certainly in some good ways. I mean, they were able to help me with college and that sort of thing.

TERRY: Did you have a religion growing up?

TIM: No.

TERRY: So was there a particular spiritual tradition in your home?

TIM: No, more atheist, or humanist.

TERRY: And yet one of the things that’s been so impressive to me, Tim, is not only have you had this intellectual grounding—which you say comes out of your family—but you have had this very strong spiritual basis with the Unitarian church, with your own sense of wildness or landscape. This is a rumor, but I want to ask: I heard you were, like, a Born Again Christian?

TIM: At one point, yeah.

TERRY: Talk to me about that.

TIM: I became that way when I was eighteen. My senior year of high school. I’d always been a jock. That was my identity. And then I had this shoulder problem for a couple years, and I finally went to the doctor and he told me that I’d broken my scapula two years earlier.

TERRY: You were a wrestler.

TIM: Yeah. And I played football.

TERRY: Talk about that.

TIM: Oh, I don’t know. That’s not very interesting.

TERRY: I think it’s really interesting. You know, high school’s a big deal. It helps form you. Wrestling is a contact sport—not unlike politics. You were really good at it.

TIM: It’s combat, more than contact.

TERRY: And it’s also mental.

TIM: Mmhmm. I mean it bred a very combative mindset for me. Something that I struggled against for a while. It took me a while to recover from that.

TERRY: How so?

TIM: It taught me to look at things from a combative perspective, and a somewhat violent perspective. It was a part of myself that I really hated when I was in high school. I didn’t really like who I was.

TERRY: As a wrestler?

TIM: As a person.

TERRY: Was it anger? I mean, I’ve got three brothers. And I watched them go through adolescence. And what you do with that kind of physicality, power, strength, anger, frustration, you know what I mean?

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: I mean, was it that?

TIM: Yeah, somewhat. It was a lot of confusion around what power and respect are, that I think a lot of young males struggle with.

TERRY: And where were you living?

TIM: In Pittsburgh.

TERRY: So you’d moved at this point?

TIM: Yeah.

TERRY: And, so you’d been told by the doctors that you had a shoulder problem.

TIM: Yeah, well, basically they took an X-ray and immediately the doctor said, “You’re done. You’re never going to wrestle again.” Because I’d broken the back of my scapula that held my shoulder in place. And so it had been sliding out for two years.

TERRY: And you had to have been in a lot of pain, right?

TIM: Yeah. And all of the soft tissue in my shoulder had stretched out, so I had to have this huge reconstructive surgery; they basically replaced everything in my left shoulder. At the end of the day, for my whole high school career, I’d go to practice. That was what I did. And it was like the second day after I’d gotten this news from the doctor that after school I didn’t have anywhere to go. I just sat in the senior lounge, and there were all these people kind of wandering around, and I had no idea what these people did with their lives. Then one of my teachers, who was a younger guy, sat down next to me and started talking. And the conversation drifted to a finding-meaning-in-life kind of discussion, and then we kept talking after that, and at some point that spring, we decided to do a religion study group kind of thing with me and a few other seniors. And so we were studying religion, and we were reading the Bible, and it was just kind of an informal thing. And then at some point I accepted it. I thought I’d found answers.

TERRY: You accepted what?

TIM: I accepted Christianity. And found something more meaningful than what I had before.

TERRY: Which was?

TIM: That, you know, there was this God who pays attention, and all that stuff. And when I went to college I got involved with some Christian clubs in a small church. And then officially became a Christian after that, and was baptized and everything.

TERRY: Which church?

TIM: It was a nondenominational Christian church. It was kind of an Evangelical church.

TERRY: Was this in Arizona?

TIM: Yeah, in Tempe. It was a big part of my life there. And then, once I moved to the Ozarks and dropped out of school, I was just kind of continuing my own search. And I gradually started to see that religion was less about having the answers and more about finding those answers—that that search was more of a lifelong process than about saying, “This is it. I’m eighteen and done.” [Laughter.]

TERRY: Was there a moment, a situation?

TIM: Around the time that I was leaving Missouri, I guess, was when I first admitted to myself that I wasn’t a Christian anymore.

TERRY: And how? How did you know that?

TIM: Just looking at my own beliefs, you know, about Jesus and things like that, and saying, “I don’t believe that in any sort of literal way. I guess that makes me not a Christian anymore.”

TERRY: I think I understand what you are saying. You know, I was raised Mormon, and a belief in Jesus Christ was an important component of my upbringing—even though there are those religious scholars who say Mormonism is not a Christian religion. But for me there really was a moment. I was teaching on the reservation, steeped in Navajo stories. In doing my thesis research, I came across Marie-Louise von Franz’s book Creation Myths. Among the many creation narratives, there was the story of Changing Woman in the Navajo tradition; there was Kali in the Hindu tradition; and then there was Adam and Eve. And I remember thinking, That’s blasphemous. Those are myths, but the story of the Garden of Eden is true. And then I thought, Really? Is that so? And it led me down this path of inquiry, not so much for meaning, but for understanding: What are the stories that we tell? You know, what are the stories that move us forward culturally. What are the stories that keep us in place? What are the stories that actually perpetuate the myths of a dominant culture or the subjugation of women? In the Book of Mormon, indigenous people are referred to as “Lamanites.” Suddenly, the doctrine I had been raised with was exposed as a form of racism. Or to say that African Americans were not worthy of the priesthood . . . issues of social justice rose to the fore. And I thought, I cannot, in good conscience, believe this. I felt like the scaffolding had been knocked out from under me.

TIM: Well, I think the powerful thing for me was when I got to the point of looking at Christianity and the Bible as more of a painting than as a photograph . . . that there were people who had this powerful experience with something bigger than themselves, and that this was their painting of it; this was how they articulated and painted that experience. But it wasn’t a photograph. And there were other groups of people in other parts of the world that had this other powerful experience with something bigger than themselves and they painted their picture of it. And, you know, we might have the same kind of experience, or have an experience with the same thing, and paint two very different pictures of it.

TERRY: A while back I was reading Albert Schweitzer’s book on historical Jesus. Do you see Jesus as a historical figure in terms of leadership?

TIM: Yeah, I do view him as an example of a revolutionary leader.

TERRY: How?

TIM: Well, he was saying very challenging things both to the people who were following him and to the dominant culture at the time. And it led to some radical changes in the way people were living and the way people were structuring society.

TERRY: What would you view as the most radical of his teachings?

TIM: Turning the other cheek, I think, is one extremely radical thing. That, I think, is his powerful message about civil disobedience. And the other, which might be even more radical, is letting go of material wealth. That’s so radical that Christians today still can’t talk about it. I mean, he said it’s easier to pass a camel through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to get into Heaven. And he told his followers to drop what they had, to let go of their jobs, to let go of their material possessions. Even let go of their families. If they wanted to follow him, they had to let go of everything they were holding onto, all the things that brought them security in life. They had to be insecure. That’s pretty radical.

TERRY: And when you look at religious leaders, when you look at St. Francis—certainly he came to that recognition. When you look at Gandhi, certainly. Thoreau was advocating simplicity. And if you look at those two tenets you just brought up, moving from the Old Testament “eye for an eye” to the New Testament’s teachings of Christ offering the alternative action of “turning the other cheek,” you see that this idea of letting go of materialism is tied to charity and love. These are two tenets that you address frequently in your speaking, right?

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: Yesterday, weren’t you saying that rich people don’t make great activists?

TIM: Yeah. In front of a very wealthy audience.

TERRY: But people understood what you were saying. I mean, we’re all privileged, right? Especially as predominantly white Americans sitting in a film festival in Telluride, Colorado.

TIM: Yeah. I also think that’s why we’re bad activists. That’s why the climate movement is weaker in this country than in the rest of the world. Because we have more stuff. We have much higher levels of consumption, and that’s how people have been oppressed in this country, through comfort. We’ve been oppressed by consumerism. By believing that we have so much to lose.

TERRY: In John de Graaf’s film Affluenza, you see what a methodical, slow process that really was to turn American culture into a culture of debt through consumption. In the 1950s, as a country, we shunned credit cards. That was not part of the frugal mind of an American. And now, not only is our national debt skyrocketing, but our personal debt as well.

TIM: Yeah, it keeps people controlled.

TERRY: By our own appetites? By our insecurities? By whom?

TIM: By those who succeed in our current system. I think our economic model, in a big sense—our whole economic system—protects itself by making people dependent upon it. By making sure that any change, any departure from that system, is going to be hard. And it’s going to lead to hardship, both individually and on a large scale as well. We can’t change our economic system without it falling apart, without things crashing really hard. Just like as an individual you can’t let go of your job and all that stuff without crashing pretty hard.

TERRY: In personal terms, your life has been in limbo for the last two years. And that’s my word, not yours. But is it fair to say you haven’t known what your future is going to be? Because you didn’t know when you were going to go to trial, or whether you’d be convicted. How has that felt?

TIM: I think part of what empowered me to take that leap and have that insecurity was that I already felt that insecurity. I didn’t know what my future was going to be. My future was already lost.

TERRY: Coming out of college?

TIM: No. Realizing how fucked we are in our future.

TERRY: In terms of climate change.

TIM: Yeah. I met Terry Root, one of the lead authors of the IPCC report, at the Stegner Symposium at the University of Utah. She presented all the IPCC data, and I went up to her afterwards and said, “That graph that you showed, with the possible emission scenarios in the twenty-first century? It looked like the best case was that carbon peaked around 2030 and started coming back down.” She said, “Yeah, that’s right.” And I said, “But didn’t the report that you guys just put out say that if we didn’t peak by 2015 and then start coming back down that we were pretty much all screwed, and we wouldn’t even recognize the planet?” And she said, “Yeah, that’s right.” And I said: “So, what am I missing? It seems like you guys are saying there’s no way we can make it.” And she said, “You’re not missing anything. There are things we could have done in the ’80s, there are some things we could have done in the ’90s—but it’s probably too late to avoid any of the worst-case scenarios that we’re talking about.” And she literally put her hand on my shoulder and said, “I’m sorry my generation failed yours.” That was shattering to me.

TERRY: When was this?

TIM: This was in March of 2008. And I said, “You just gave a speech to four hundred people and you didn’t say anything like that. Why aren’t you telling people this?” And she said, “Oh, I don’t want to scare people into paralysis. I feel like if I told people the truth, people would just give up.” And I talked to her a couple years later, and she’s still not telling people the truth. But with me, it did the exact opposite. Once I realized that there was no hope in any sort of normal future, there’s no hope for me to have anything my parents or grandparents would have considered a normal future—of a career and a retirement and all that stuff—I realized that I have absolutely nothing to lose by fighting back. Because it was all going to be lost anyway.

TERRY: So, in other words, at that moment, it was like, “I have no expectations.”

TIM: Yeah. And it did push me into this deep period of despair.

TERRY: And what did you do with it?

TIM: Nothing. I was rather paralyzed, and it really felt like a period of mourning. I really felt like I was grieving my own future, and grieving the futures of everyone I care about.

TERRY: Did you talk to your friends about this?

TIM: Yeah, I had friends who were coming to similar conclusions. And I was able to kind of work through it, and get to a point of action. But I think it’s that period of grieving that’s missing from the climate movement.

TERRY: I would say the environmental movement.

TIM: Yeah. That denies the severity of the situation, because that grieving process is really hard. I struggle with pushing people into that period of grieving. I mean, I find myself pulling back. I see people who still have that kind of buoyancy and hopefulness. And I don’t want to shatter that, you know?

TERRY: But I think that what no one tells you is, if you go into that dark place, you do come out the other side, you know? If you can go into that darkest place, you can emerge with a sense of empathy and empowerment. But it’s not easy, and there is the real sense of danger that we may not move through our despair to a place of illumination, which for me is the taproot of action. When I was studying the Bosch painting The Garden of Earthly Delights, I was really interested in finding the brightest point in the triptych. I remember squinting at the painting and searching for the most intense point of light. To my surprise, the brightest, the most numinous point was in the right corner of Hell. That’s where the fire burned brightest. And that was something I recognized as true. My mother had just died, my grandmother had just died, my other grandmother had just died. You know, there’s a Syrian myth of going into the Underworld, and when you emerge, you come out with what they call “death eyes”—eyes turned inward. I had been given “death eyes.” I had been changed. I had a deeper sense of suffering but I also felt a deeper sense of joy. Hard to explain, but I remember someone saying to me, “Terry, you’re married to sorrow.” And I said, “No, I’m not married to sorrow, I just refuse to look away.” You stay with it—we are stronger than we know. But it isn’t easy. And you don’t have any assurance that you’re going to find your way out. And there’ve certainly been days where I’ve wondered . . .

TIM: Mmhmm. And the other powerful thing that was happening in my life in 2008 was that I was coming out of the wilderness. I mean it had always been a big part of my life growing up. All of our family vacations were in the wilderness.

TERRY: Where?

TIM: West Virginia. New Hampshire. Montana. Wyoming. Everywhere we could go. And so it always had an important influence on me. I remember when I was seventeen? Sixteen? I was struggling with all this teenage angst, and being overwhelmed with the world, and I had this feeling that I just wanted things tostop for a while so that I could catch up. And I told my mom at one point that I was going to pretend that I was crazy and get myself checked into a mental institution so that I could spend a few weeks where people wouldn’t expect me to do anything other than just stare out the window and drool. And she convinced me that that was a bad idea [laughter], with some potentially long-term consequences—like a lobotomy. And she said, “You need to go to the wilderness.”

TERRY: Wow.

TIM: We were living in Pittsburgh at the time, and she sent me down to West Virginia, to the Otter Creek Wilderness, in the Monongahela National Forest, which was a place that I’d been to several times. And I spent eight days alone there. And it was a really powerful experience that led to my formation as an individual. I mean, it was the first time that I ever experienced myself without any other influences. Without any cultural influences, any influences from other people. And it was terrifying to experience that—I mean I really thought I was actually going crazy at that point. But it allowed me to develop that individual identity of who I was without anyone else around. And then it continued to play a bigger role in my life once I went to college. I started an outdoor recreation and conservation group my freshman year. And I spent every weekend out in the desert somewhere in Arizona. Then I dropped out after two years to go work with kids in the wilderness, in the Ozarks. And did that for three years, and then came to Utah to work for a more intense wilderness therapy program—with troubled teens. And during that time I was fully into the wilderness. Especially when I moved to Utah, I was out there all the time. That was where I lived. And I did feel like I had escaped, in a lot of ways. I felt free, I felt like whatever shit was going on in the world didn’t affect me. I didn’t watch the news, I didn’t know what was going on in the world. And I didn’t think it mattered to me.

TERRY: And what effect would you say the Utah wilderness had on you as a young man?

TIM: Well, it put me in perspective. I think especially the western landscapes have done that for me because they’re so big and so open. You know, when you spend all your time in a little room, you feel very big and very important, and everything that happens to you is a big deal. And when you’re out in the desert, you see that you’re really small. And that’s a very liberating sense—of being very small. Every little thing that happens to you isn’t that big a deal. Going to prison for a few years—it’s not that big a deal. But also just my views on how to live, and what actually makes me happy; how to form a little community out there with a few people; how human actions really work when there isn’t a TV telling us what to do—that all formed out there. And I think that’s part of why some people fight against wilderness, fight to extinguish all of it. I mean, I think there’s definitely a lot of folks who don’t understand it, and have never experienced it. But I think some of the opponents of wilderness really do understand it. They understand . . .

TERRY: Its power.

TIM: That it’s a place where people can think freely. Tyranny can never be complete as long as there’s wilderness. But eventually I wanted to come back. And that’s where I see one of those lessons of Jesus going out to the wilderness for a long time and then coming back and being an activist. What I experienced when I came out of the wilderness and went back to school was just outrage with society. And complete intolerance for the world. Just constantly saying, “How the hell could people live this way? How the hell could people accept this as being okay?” So many things about our society, I just kept looking at them after being in the wilderness for so long and saying, “How the hell could people accept this? This is outrageous.” And I think that’s one of the things that the wilderness does for us, you know, it allows us to live the way we actually want to live for a while. It puts things in the perspective of, “Wait, this isn’t inevitable. It doesn’t actually have to be this way. And this isn’t the way I want to live. It’s not okay.” I think activism at its best is refusing to accept things. Saying that this is unacceptable. And I felt that so strongly sitting there at the auction, watching parcels go for eight or ten dollars an acre. I mean that’s why I first started bidding—just to drive up the prices—because I had this overwhelming sense that this is not acceptable.

TERRY: I remember having a conversation with Breyten Breytenbach, who wrote The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist, who spent time in prison in South Africa for being anti-apartheid. We were in a bus driving to Mexico City, and he said to me, “You Americans, you’ve mastered the art of living with the unacceptable.” And that haunted me. For decades, his statement has haunted me. From that point forward, I’ve kept thinking about what is unacceptable. And that’s what I hear you saying: that it was unacceptable from your standpoint that these public lands, these wild places that you knew by name and in a very physical, spiritual way, were being sold for eight dollars an acre.

TIM: Mmhmm. There’s so much acceptance. And, I don’t know, I think tolerance is the enemy of activism.

TERRY: That’s interesting. Because if you talk about empathy, and turning the other cheek, then tolerance takes on another definition. Doesn’t it?

TIM: I don’t know. I wouldn’t consider turning the other cheek “tolerating violence.”

TERRY: What’s the difference between tolerance and compassion? I don’t mean tolerating a situation, but really practicing tolerance.

TIM: The compassion actively works to undermine injustice and violence. For me, that’s kind of the misinterpretation of the whole turn-the-other-cheek thing, that it’s about tolerating the violence. I mean, to me it’s about actively ending the violence. It’s the most effective weapon we have against violence: turning the other cheek.

TERRY: But what about racial intolerance? Or intolerance of another species, like prairie dogs—if you turn that word around?

TIM: Yeah, but if you’re tolerating prairie dogs, it’s because you don’t like prairie dogs. I mean, I don’t like the idea of toleratingother races. I don’t like the idea that it’s something we put up with. The idea of tolerating different people, to me, is not something that I’m comfortable with—and when I look at the modern environmental movement, to bring it back to that, I think it’s defined by what we accept. By what we speak out against, but ultimately accept. You know, we’ll sign a petition, or even do an action, or even get arrested for a day, but ultimately we’re gonna go back to our normal lives. Ultimately we’re going to keep participating in this system.

TERRY: You know, it was interesting, I was listening to Robert Pinsky speak, and he was talking about the word medium. Like, what is the writer’s medium, what is the poet’s medium? And he was saying that a poet’s medium is his body, or her body. And thatmedium is “in between.” So that immediacy is “nothing in between.” And I hadn’t thought about that . . . that there are so many words where we don’t know what the root is, and knowing that could help inform our discussions. You know, what is an activist’s medium? I mean, what would you say your medium is? If a poet’s medium is his or her body—because it’s voice, it’s breath, it’s animating language, it’s sound—what would an activist’s medium be?

TIM: I would say it’s the same as a poet. I would say it’s my body or my life. It’s that which I use to reach other people. It’s the interaction between me and society.

TERRY: I mean, you are laying your body down. You sat your body down, right? In the auction.

TIM: I raised it up. [Laughter.]

TERRY: So tell me about that moment when you picked up the paddle and then started winning. You know, when you were bidding them up, but you weren’t really bidding to win. At the trial, Agent Love was saying, “And, if you looked, he was looking over his shoulder! Here’s the photograph that shows there was a deep conspiracy as he kept looking into his bag, you know, looking to see who else was in the room.”

TIM: Well, so many of the things he brought up were to try to frame me as, like, this shady character.

TERRY: And a medium for a bigger interest, right?

TIM: Yeah. Like the fact that I was looking over my shoulder, and they have this photograph. I remember that moment so clearly. I was amazed when I first saw that picture—I could see by the look on my face that that’s when I was looking at Krista [Bowers], who was on the other side of the room. And she was crying.

TERRY: And you knew her through the Unitarian church?

TIM: Yeah. And it was so clear to me that she was overwhelmed by the heartlessness of this whole scenario. And, you know, when you see a woman crying you feel like you have to do something about changing the situation that’s causing that.

TERRY: Was it really just an act of chivalry? Or when you saw her tears, were they really your tears too?

TIM: She was clearly feeling it as sadness. But for me, it was going into outrage. I was turning it more outward, where she was turning it inward—but the depth of her emotion justified the depth of my own emotion, and was something that pushed me to act. When Agent Love—

TERRY: Not to be confused with Bishop Love, from Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang . . .

TIM: Exactly. No, but when Agent Love was talking about how I was looking at my phone, he said that I was sending text messages. But I’d never even sent a text message at that point. What I was doing, once I was winning parcels, was pulling a phone number out of my phone and writing it down on the back of a business card and handing it to my roommate, who was sitting next to me, and saying, “You need to go call my friend Michael and tell him that I need help.”

TERRY: Paying for these.

TIM: Yeah. [Laughing.]

TERRY: Did you think about the consequences?

TIM: Yeah.

TERRY: And it was worth it.

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: So you were there because of the wilderness. Was climate change part of it? Or did it become a larger issue afterward? Because I’m interested in how stories change, evolve.

TIM: It was much more climate change than the wilderness. For me, the wilderness was the third most important issue. The first was climate change, the second was the attack on our democracy, and the fact that people were locked out of the decision-making process with this. And, you know, something I realized last year, when I was on a panel with Dave Forman and Katie Lee, and they were talking about their motivations for protecting wilderness, doing this for the coyote, and all that stuff. And I realized that I was coming from a completely different place than them. I would never go to jail to protect animals or plants or wilderness. For me, it’s about the people. And even my value of wilderness is about what it brings to people. I have a very anthropocentric worldview.

TERRY: And do you think that goes back to your basic spiritual perspective that set you out on this path with Christianity?

TIM: I don’t know. I don’t think so.

TERRY: Because that is a much more human-centered philosophical starting point.

TIM: Yeah. Well, I think it goes beyond that. I think it’s just what I’ve learned to value in my life. I’ve spent a lot of time with people, and I’ve spent a lot of time with animals and the wilderness, and it’s the people that I really value, at a totally different level than anything else. And that’s when I started wondering whether I was actually an environmentalist. [Laughter.]

TERRY: Again, we go back to language. What does an environmentalist mean, anyway? What does a Christian mean? What does an activist mean? I mean, if we took away all these loaded words, or even stopped using war terminology . . . I’m aware of the aggression of language, of “fighting” or “combating” or “war.” How do we take the violence out of our language? How do we become less oppositional and more inclusive in how we talk about these issues? I don’t know. This is what I struggle with. Because I would say that your approach is confrontational.

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: And yet, you’re asking that we sing songs. That it not be confrontational.

TIM: No. That it be more effective confrontation. That it be stronger confrontation than what violence can do.

TERRY: But the organization that you and Ashley [Anderson] began—Peaceful Uprising—I love those two words because they’re paradoxical, right?

TIM: Are they?

TERRY: Well, what I hear you saying in Peaceful Uprising is, “We will create an uprising, but it will be peaceful.” You know, “We will create a confrontational presence, but we will do it singing.”

TIM: Yeah. And I think that’s a strategic decision, rather than a moral one.

TERRY: How so?

TIM: I mean, my commitment to a nonviolent movement ultimately comes down to the fact that it’s more effective.

TERRY: And how did you come to know that?

TIM: I think the reality of the climate crisis—and all the other crises facing us as humanity today—justify the strongest possible tactics in response. Demand the strongest possible tactics. And I think that requires nonviolent resistance.

TERRY: Is violence ever justified?

TIM: Well, it’s justified. But that doesn’t mean it makes sense. I mean, if you’re talking moral justification, yeah—to prevent the collapse of our civilization, and the deaths and suffering of billions of people, it’s morally justified. But violence is the game that the United States government is the best in the world at. That’s their territory.

TERRY: And when you talk about growing up, it was your own confrontation with the violent part of yourself that was most problematic for you.

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: And so, you’ve had to figure out how to use that anger or rage constructively.

TIM: Yeah, I mean that’s something I struggle with: the common liberal mindset that says, “Oh, we don’t want those negative emotions like anger and outrage and fear.” To me that doesn’t make sense—that those are negative emotions.

TERRY: In the same way we don’t want to grieve.

TIM: Those are real emotions. Those are part of human nature. We evolved with those emotions for a reason. Because all the people who were threatened, and didn’t feel fear, or whose children were threatened, and they didn’t feel outrage—those people all died off. And now that we’re facing these very real threats to ourselves and our children, if we don’t feel and find a way to constructively use anger and outrage and fear—

TERRY: And indignation.

TIM: —we should expect to meet the same fate as all those dead-end roads of human evolution.

TERRY: But if it’s true, what Terry Root first told you—that there is no hope—then what’s the point?

TIM: Well there’s no hope in avoiding collapse. If you look at the worst-case consequences of climate change, those pretty much mean the collapse of our industrial civilization. But that doesn’t mean the end of everything. It means that we’re going to be living through the most rapid and intense period of change that humanity has ever faced. And that’s certainly not hopeless. It means we’re going to have to build another world in the ashes of this one. And it could very easily be a better world. I have a lot of hope in my generation’s ability to build a better world in the ashes of this one. And I have very little doubt that we’ll have to. The nice thing about that is that this culture hasn’t led to happiness anyway, it hasn’t satisfied our human needs. So there’s a lot of room for improvement.

TERRY: How has this experience—these past two years—changed you?

TIM: [Sighing.] It’s made me worry less.

TERRY: Why?

TIM: It’s somewhat comforting knowing that things are going to fall apart, because it does give us that opportunity to drastically change things.

TERRY: I’ve watched you, you know, from afar. And when we were at the Glen Canyon Institute’s David Brower celebration in 2010, I looked at you, and I was so happy because it was like there was a lightness about you. Before, I felt like you were carrying the weight of the world on your shoulders—and you have broad shoulders—but there was something in your eyes, there was a light in your eyes I had not seen before. And I remember saying, “Something’s different.” And you were saying that rather than being the one who was inspiring, you were being inspired. And rather than being the one who was carrying this cause, it was carrying you. Can you talk about that? Because I think that’s instructive for all of us.

TIM: I think letting go of that burden had a lot to do with embracing how good this whole thing has felt. It’s been so liberating and empowering.

TERRY: To you, personally?

TIM: Yeah. I went into this thinking, It’s worth sacrificing my freedom for this.

TERRY: And you did it alone. It’s not like you had a movement behind you, or the support group that you have now.

TIM: Right. But I feel like I did the opposite. I thought I was sacrificing my freedom, but instead I was grabbing onto my freedom and refusing to let go of it for the first time, you know? Finally accepting that I wasn’t this helpless victim of society, and couldn’t do anything to shape my own future, you know, that I didn’t have that freedom to steer the course of my life. Finally I said, “I have the freedom to change this situation. I’m that powerful.” And that’s been a wonderful feeling that I’ve held onto since then.

TERRY: Are you surprised by this?

TIM: Yeah. And I think that’s where some of that lightness has come from. And also seeing that it’s having an impact. That it’s firing some other people up, that it’s embarrassing the government. I mean, one of the great things about the trial was seeing how vulnerable the U.S. attorney felt. He was freaking out all the time. And he was terrified. I mean, the government was terrified just that people showed up for the trial. They were terrified by the fact that all these other people are worrying about how to keep me out of prison—

TERRY: I’m one of them.

TIM: [Laughs.] I feel like the goal should be to get other people in prison. How do we get more people to join me? Because that’s where the liberation is, that’s where the effectiveness is.

TERRY: Is that the only alternative?

TIM: No. [Pause.] But it’s one that feels good.

TERRY: For you.

TIM: Yeah.

TERRY: So what are some of the alternatives for those who maybe don’t have that option. Maybe they’ve got children. You know what I’m saying?

TIM: Well, everybody has a reason why they can’t.

TERRY: But I was aware when I was arrested in front of the White House, protesting during the buildup to the Iraq war, that when I looked around, it was a lot easier for me to be arrested than others, you know? I didn’t have a traditional job, I didn’t have children. I mean, some people have more at stake than others. And you’re right, there’s every reason not to. But I’m just playing devil’s advocate. Civil disobedience is one path. It’s a path I’ve personally chosen at times—certainly not with the stakes as high as they are for you. But it’s an act that I powerfully support and believe in and have subscribed to. But what about other alternatives?

TIM: If people aren’t willing to go to jail, there are alternatives in which they can be powerful and effective. But if people feel they’ve got too much to lose—they’ve got all this other stuff in their life, and they might be risking their job, or their reputation, and things like that—I don’t think they can be powerful in other ways.

TERRY: So you can’t be powerful as an organizer or as a support person behind the scene? Or as a teacher or educator?

TIM: You can, but I don’t think people are going to realize their power as revolutionaries if they feel like they’ve got all this stuff to lose.

TERRY: If there’s only one way—which is arrest—then I would argue that you sound like a true believer.

TIM: No, I’m not saying that’s the only way. I’m saying that thewillingness for that is what’s necessary. That willingness to not hold back, to not be safe. People can do it without getting arrested. But people can’t be powerful if their first concern is staying safe.

TERRY: Okay. So that’s different than being arrested.

TIM: Yeah. I’m just using that as an example of that level of risk.

TERRY: What I hear you saying is breaking set with the status quo, pushing the boundaries of whatever venue we choose to be active in.

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: Because I think what is killing us is the level of comfort, this of complacency. What you have said repeatedly is one person can make a difference, we are powerful, we can disrupt the status quo, right? Even at a multimillion-dollar oil and gas auction. And if the government isn’t going to do it for us, if our nonprofits aren’t going to do it, if the environmental movement isn’t going to do it, who’s going to do it? We can no longer look for leadership beyond ourselves.

TIM: Yeah, exactly. And I think our current power structures only have power over us because of what they can take away from us. That’s where their power comes from—their ability to take things away. And so if we have a lot that we’re afraid of losing, or that we’re not willing to lose, they have a lot of power over us.

TERRY: And that goes back to your own sovereignty of soul—of really knowing who you are, knowing what your intention is, and having the strength to go forward. That’s why I was so interested in what led you up to that moment, because in a way, your whole life prepares you for that moment, when you look your divine soul in the face and say, “Okay, do I have it in me to act now?”

TIM: Mmhmm.

TERRY: Because, for most of us, it’s not a planned thing—there is no choice to be made. It’s just, this is the next step that you take, because everything prior to that moment has prepared you for that, you know? Mardy Murie once said, “Don’t worry about your future. There’s just usually enough light shining to show you the next step you’re going to take.” And then, when that perfect alliance comes, when your spirit is aligned with your destiny, then an action occurs that’s revolutionary.

TIM: Something that I’ve related to through this is the Annie Dillard quote, “Sometimes you jump off the cliff first, and build your wings on the way down.” That’s how I felt in this whole process. First I didn’t know what I was going to do at the auction, but I knew I was going to disrupt it. And then, after disrupting it, I had no idea who was going to support me and how that was going to play out. And no idea whether or not I could handle that role. I mean, I can’t say I even had any understanding or expectation that it would put me in this kind of role. But even to the extent that I knew it would put me in some kind of role, I had no idea whether or not I could handle it.

TERRY: And how are you?

TIM: I feel like I’m perfectly suited for this.

TERRY: [Laughter.] I love your honesty! I mean, it appears so. Is that a surprise?

TIM: Yeah. I’d never given a public speech before this. And now I feel like I can just roll right into it any time. And people are responding when I speak. I mean, I had no idea that that would be the case. And I don’t even know that it ever would have been. I don’t know if any of these skills or abilities ever would have been developed had it not been for the necessity of the situation.

TERRY: And that’s where I would go back to intention. I think your intention was really pure. You didn’t know what the outcome was going to be. It feels like you just keep moving. And when we talk about a movement, I think you’re really showing us what that movement looks like. And I don’t even like the word movement. For me, it’s: how do we build community around these issues?

TIM: Yeah. I mean I gave a whole speech about that last fall, about the difference between a climate lobby and a climate movement. I talked about the need to build a genuine climate movement. But I like the idea of a community that supports people. I feel like that’s what we’re building with Peaceful Uprising.

TERRY: Each person has a role to play, according to what they do best. I love that you said, “I’m perfectly suited for this.” There are other people that aren’t.

TIM: Yeah.

TERRY: And so, I think for each of us to find our own path in the name of community, you know, if each of us finds our own niche, with our own gifts, each in our own way and our own time, change can occur. Radical change. And for me, Tim, this is how you have inspired me: We all need to take that next step, whatever that looks like, for the integrity of our own lives. And when I asked you, “How can I support you?” you said, “Join me. Get arrested.” But it’s easy to get arrested, really. I’ve done it more times than I can count. That’s not my risk, at this point, as a fifty-five-year-old person. But the challenge that I heard was: What’s the most uncomfortable thing you can do—the greatest risk, with the most at stake? And I can’t answer that right now. But I’m going to be thinking about that, and figuring out what that next step is for me both as a writer and a person.

TIM: I think what I was really trying to get across was the idea of not backing down. Because it’s important to make sure that the government doesn’t win in their quest to intimidate people into obedience. They’re trying to make an example out of me to scare other people into obedience. I mean, they’re looking for people to back down.

TERRY: Right. And I think democracy requires participation. Democracy also requires numbers. It is about showing up. And we do need leadership. And I think what your actions say to us as your community is, “How are we going to respond so you are not forgotten? So that this isn’t in vain?” And I think that brings up another question: we know what we’re against, but what are we for? Our friend Ben Cromwell asked this question. What are youfor? What do you love?

TIM: I’m for a humane world. A world that values humanity. I’m for a world where we meet our emotional needs not through the consumption of material goods, but through human relationships. A world where we measure our progress not through how much stuff we produce, but through our quality of life—whether or not we’re actually promoting a higher quality of life for human beings. I don’t think we have that in any shape or form now. I mean, we have a world where, in order to place a value on human beings, we monetize it—and say that the value of a human life is $3 million if you’re an American, $100,000 if you’re an Indian, or something like that. And I’m for a world where we would say that money has value because it can make human lives better, rather than saying that money is the thing with value.

TERRY: I think about the boulder that hit the child in Virginia. What was that child’s life worth—$14,000? The life of a pelican. What was it—$233? A being that has existed for 60 million years. What do you love?

TIM: I love people. [Very long pause.] I think that’s it.

TERRY: I think that’s why people are inspired. Because I think they feel that from you. And I really feel if we’re motivated by love, it’s a very different response. Here’s an idea that I want to know what you think of: Laurance Rockefeller, as you know, came from a family of great privilege, and he was a conservationist. And in his nineties, he informed his family that the JY Ranch—the piece of land in Grand Teton National Park that his father, John D. Rockefeller, set aside for his family—would be returned to the American people. This was a vow he had made to his father. And he was going to “rewild it”—remove the dozens of cabins from the land and place them elsewhere. Well, you can imagine the response from his family. Shocked. Heartsick. Not pleased. But he did it anyway, and he did it with great spiritual resolve and intention. He died shortly after. I was asked to write about this story, so I wanted to visit his office to see what he looked out at when he was working in New York. Everything had been cleared out, except for scales and Buddhas. That was all that was in there. I was so struck by that. And his secretary said, “I think you would be interested in this piece of writing.” And she disappeared and she came back, and this is what she handed me: [Reading] “I love the concept of unity and diversity. Most decisions are based on a tiny difference. People say, ‘This was right, that was wrong’; the difference was a feather. I keep scales wherever I am to remind me of that. They’re a symbol of my awareness. Of the distortion most people have of what is better and what is not.” How would you respond to that? The key sentence, I think, is, “The difference was a feather.”

TIM: Yeah, the difference is a feather. I guess that’s why I believe that we can be powerful as individuals. Why we actually can make a difference. The status quo is this balance that we have right now. And if we shift ourselves, we shift that scale. I remember one of the big things that pushed me over the edge before the auction was Naomi Klein’s speech that she gave at Bioneers in November of 2008. She was talking about Obama, and talking about where he was at with climate change, and the things he was throwing out there as campaign promises, you know, the best things he was offering. And she was talking about how that’s nowhere near enough. That even his pie-in-the-sky campaign promises were not enough. And she talked about how, ultimately, Obama was a centrist. That he found the center and he went there. And that that’s where his power came from. She said, “And that’s not gonna change.” And so if the center is not good enough for our survival, and if Obama is a centrist, and will always be a centrist, then our job is to move the center. And that’s what she ended the speech with: “Our job is to move the center.” And it was so powerful that we actually got the video as soon as we could and replayed it at the Unitarian church in Salt Lake, and had this event one evening where we played that speech and then broke up into groups and talked about what it meant to move the center. And what I came away from that with was the realization that you can’t move the center from the center. That if you want to shift the balance—if you want to tilt that scale—you have to go to the edge and push. You have to go beyond what people consider to be reasonable, and push.

TERRY: I think that’s so true.

TIM: And that’s what I thought I was doing at the auction—doing something unreasonable.

TERRY: Rather than just standing outside with placards, you came inside.

TIM: To make the people standing outside with placards look reasonable.

TERRY: Which was Earth First!’s tactic early on, right?

TIM: Yeah.

TERRY: You know, with Breyten Breytenbach, going back to that comment, “You Americans have mastered the art of living with the unacceptable,” my next question to him was, “So what do we do?” And he said, “Support people on the margins.” Because it’s from the margins that the center is moved.

TIM: Yeah, that margin—that’s the feather. I mean, with climate change, the center is this balancing point between the climate scientists on one side saying, “This is what needs to be done,” and ExxonMobil on the other. And so the center is always going to be less than what’s required for our survival.