Q: I’m trying to construct a family of women who have a congenital heart defect. The mother has died from it. The older sister dies as the book begins. The middle sister is suffering and her imminent death is part of the plot. (She’s 18). What I’d like to have is for her to be able to be treated by surgery, but a surgery the poor girl couldn’t afford. The youngest (12) may or may not have the problem. (I can live with either.) So far, I’ve found coarctation of the aorta but I have no clue what it means. Could the older sister simply have a worse and inoperable version?

David Corbett, author of Do They Know I’m Running?

http://www.davidcorbett.com

A: Coarctation would work as would an Atrial Septal Defect (ASD) or Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD). Each, if untreated, can lead to death over time and each can be repaired.

For the circumstance you described, I would go with the ASD. This is by definition a congenital heart problem so your two young ladies would both be born with a defect. The severity and the rate of progression and the time it takes to become inoperable are dependent upon two things–the size of the defect and time.

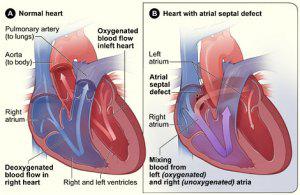

Let me explain a little bit of the physiology which is very complex but hopefully I can make it understandable. The normal circulation of the blood is divided into two separate parts. The systemic or arterial circulation is the left side of the heart and the arteries and veins throughout the body. The blood pressure in this part of the circulation is the blood pressure a doctor obtains in the office. The other half of the circulation is the right sided or pulmonary circulation. This is the circulation that goes through the lungs. So the blood is pumped from the left side by the left ventricle out to the body and returns to the right atrium through the veins. The right side of the heart, the right ventricle, pumps the blood in the lungs and it returns to the left atrium through the pulmonary veins. It’s just a large figure of eight. The two sides of the circulation are completely separate and have no communications. But in a ventricular or supple defect the two sides are exposed to one another by the defect. In a VSD the defect is in the ventricular septum which separates the left ventricle from the right ventricle. In an ASD the defect is in the atrial septum which separates the left atrium from the right atrium.

The pressure throughout the left side are much higher than are those on the right. For example the systemic systolic pressure–the one obtained when your blood pressure is taken–is typically around 120 while the pulmonary systolic pressure–the pressure in the pulmonary that carries the blood to the lungs–is typically around 30. As long as the two sides are separated there is no problem but when a defect appears the blood preferentially goes through the defect from the left side to the right side. In the case of atrial septal defect what happens is that the blood returning from the lungs into the left atrium splits. Part of it goes on to the left ventricle and is pumped out to the body as would be normally expected but part of it, driven by this pressure differential, crosses over the defect into the right side of the heart. I think you can see that as the system went on beat by beat that more blood flows through the right side and the left side simply because some of the blood destined for the left side is diverted or shunted over to the right side through the defect. So the pulmonary blood flow is elevated in either an ASD or a VSD. As the years go by this increase flow causes alterations in the blood vessels of the lungs so that they become thicker and this causes the right-sided pressure to go up.

As long as this pressure is below 40 or 50 the person does fine. From 50 to 70 or so they develop weakness and shortness of breath particularly with any activity. Once the pressures reach 80 or 90 the lung diseases severe and these individuals are typically inoperable. With pulmonary artery pressures that are normal or only slightly elevated the risk of the surgery is extremely low. When the pressures reach the 50 to 70 range the surgery is a little more risky but still is easily doable and most of these people do well. Once the pressure reaches the 80 to 100 range operations no longer work simply because if you close the defect heart failure will result in the patient will die. If not immediately fairly soon. The physiology they are way too complex to explain but suffice it to say that’s what happens.

So the bottom line is that one of your young ladies could have a defect that was smaller than her sister. This means that her sister might develop elevated pressures and severe symptoms by age 15 to 20 whereas the sister with a smaller defect may not get out of trouble till she’s in her 30s or 40s. There can be that much variation and it all depends upon the size of the defect. So this should give you a lot to work with with your two young ladies.

The standard treatment for this is open-heart surgery where a patch is sewn over the defect. This does require being put on the heart lung machine. Newer techniques where the patch is pushed through a catheter and then expanded to close the defect are now very common. This does not require opening the chest or the use of the bypass machine and is typically done in a Cardiac Cath Lab. In the former the patient is in the hospital for 5 to 7 days after surgery, while in the latter they often go home the next day. Both were expensive procedures so either would fit your requirements.