I’ve been spending quite a bit of time thinking about Harold Bloom in the context of my series of posts on the Greatest Of All-Time Literary Critics, which has become, as I knew it would, mostly about the nature of the discipline, but as examined by the world of several thinkers – for neither Lévi-Strauss nor Derrida were literary critics, though they were important to the evolving discipline. Bloom may be as brilliant a thinker as academic literary criticism has seen, but it’s not at all clear to me that he has had a distinctive influence on the discipline and I rather suspect that his value as public spokesperson for literature will become heavily discounted over time. But I’ll save those arguments for my main post on Bloom.

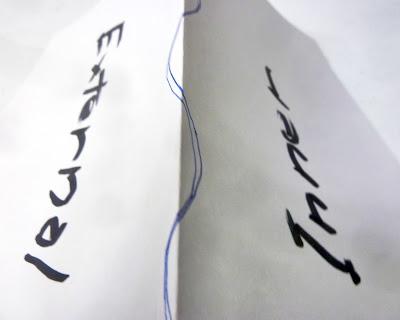

In this post I want to think about the peculiar nature of literary criticism, for thinking about Bloom has forced me once again to think about this. And I think I’ve made some progress. Consider this crude image, in which Reality is depicted as a sheet of paper with a fold in it:

To the left we have the external world, the world studied by physicists, geologists, biologists, but also economists. To the right we have the inner world, a collective world we experience, elaborate, and share through religion and the arts. Literary criticism, that double blue line in the image, exists in both worlds, rather precariously so.

That is true for all aesthetic objects. In the case of paintings, sculptures, and works of music seems to carry the meaning rather directly whereas in literary works the meaning resides in the meanings of words, which don’t exist in the physical form. Critics of music and of the plastic arts have the physical objects they can talk about. But the physical objects literary critics deal with, symbols on paper, are of little interest in themselves. Critics must instead talk about what those symbols imply and mean, and that’s tricky and deeply problematic. The problematic nature of that activity didn’t hit home until the 1960s or so, when critics realized that they weren’t reaching consensus on their interpretations. How could literary criticism be a proper intellectual discipline if critics can’t agree? I’ve already devoted two posts to this problem (René Girard prepares the way for the French invasion and Derrida deconstructs the signs while Lévi-Strauss tracks the system of myth) and so don’t intend to rehearse that material again.

In reading around in The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, but also the much earlier Anxiety of Influence, it’s clear that Bloom yearns for a criticism that is very much intertwined with the (collective) inner realm. At one point he says something to the effect that the meaning of a poem is another poem (that’s what influence is about). So the critic cannot tell us about that meaning ‘from the outside.’ Rather the critic must bath in it, if you will.

One of his last books, which I’ve not looked at, is entitled The Anatomy of Influence (playing on his own earlier book and Northrup Frye’s still earlier one). Sam Tanenhaus reviewed it in the New York Times in 2011 where he said:

The critic, his antennae sharpened, was the poet’s secret sharer or, perhaps, his unrecruited psychoanalyst. “If to imagine is to misinterpret, which makes all poems antithetical to their precursors, then to imagine after a poet is to learn his own metaphors for his acts of reading.” This erased the barrier separating critic from poet. Each, an impassioned reader, annexed the functions of the other.

For the strong misreading poet and critic, there was but one ambition, to achieve the sublime, the highest form of spiritual-aesthetic exaltation, mingled with intimations of terror, first described in antiquity by Longinus ...

That’s what Bloom seems to have been about, erasing “the barrier separating critic from poet” so that the two have “but one ambition, to achieve the sublime, the highest form of spiritual-aesthetic exaltation.”

That’s what drove Bloom to all but worship what he called “the aesthetic,” without, so far as I know, attempting to define it. The aesthetic lives in the actions of that inner world. To attempt to define it, examine and analyze it, to explain it, would be to step aside and project it into the the external world. He opens The Western Canon with these two sentences:

This book studies twenty-six writers, necessarily with a certain nostalgia, since I seek to isolate the qualities that made these authors canonical, that is, authoritative in our culture. “Aesthetic value” is sometimes regarded as a suggestion of Immanuel Kant's rather than an actuality, but that has not been my experience during a lifetime of reading.

He invokes that aesthetic many times but he never attempts to explicate it. It is self-evidently there, given in (his) experience.

For Bloom the canon, and Shakespeare above all, defines the aesthetic. That is what he is setting over against the external world. His job as critic is to dwell in the aesthetic. The extremism of his Bardolatry, in which he often compares Shakespeare to God, is an attempt to make Shakespeare as REAL as possible, and thereby make the CANON as REAL as possible. It’s an act of glorious desperation. Writing in a collection of essays about Bloom’s Shakespeare, Linda Charnes observes [1]:

One cannot help but feel that Bloom wants to be regarded not as an interpreter of Shakespeare, but as his “partner in communication,” and – most hysterically–regarded thus by Shakespeare himself.

What, in the end, though, is the point? Does reading Bloom on Shakespeare or the canon send readers back to those texts, renewed with new insight, or does it simply enmesh them in Bloom’s erudition, judgement, and mythification? Is there anything in Blooms criticism other than Bloom?

* * * * *

[1] Linda Charnes, “The 2% Solution: What Bloom Forgot,” in Christy Desmet and Robert Sawyer, eds., Harold Bloom’s Shakespeare, Palgrave, 2001, pp. 259-268.