Last month, Isobel turned three, the minimum legal age at which she could be assessed for the mobility component of Disability Living Allowance (DLA). The renewal claim form was posted to me last spring, and I submitted it only two weeks ago. The process of filling it in has been arduous, slow and depressing, and for a good reason – it’s 41 pages long.

In light of this I cannot understand how the coalition government could have forced through the Welfare Reform Bill last year with the repeated insistence that disabled people and their families were work-shy benefit scroungers. (Trade Union Congress are just the latest in a long line of people who accuse them of lying to get what they want.)

You’d have to be living with a disability, or caring as regularly for a child with a disability as I do, to be able to navigate the DLA claim form effectively. Faking it is almost impossible – indeed, the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) puts the fraud rate as just 0.5%.

All of which proves what? That disability is consistent only with its own nature – not others’ perceptions of it. It can evolve, deteriorate, go into remission or lead to complications. People with CP can play golf one day, be in a wheelchair the next.

Disability can strike at any time, and doesn’t discriminate (unlike governments). That impairment comes in many myriad forms is a reflection not of how well people lie, but how intricate the human body is as a mechanism.

So, all well and good. Right? Well, not exactly.

That DLA claim form is 41 pages long because we are living in a society that doesn’t regard people with disabilities as equal. That society was constructed primarily with non-disabled people in mind, all the way from the buildings that we live and work in, the transport we use, the food we eat, to the technology that we operate our lives with.

To someone unfamiliar with the word ‘access’, it’s hard to explain. If you were a non-disabled person working the night shift at the local supermarket and you got the bus to work without hassle, you wouldn’t be able to understand why your disabled colleague was complaining so much. And the pure and simple reason would be this: that you had full access on a plate, and for so long that you took it for granted, to the extent that you didn’t even know what ‘access’ meant – except perhaps where ‘internet’ preceded it.

A minority though we might be in today’s society, the statistics research boffins come up with (the Office for National Statistics being one) aren’t as straightforward as they’d like you to think: 8 million? 9 million? 12 million? It’s not just a matter of people being prepared to declare their impairments (or not), but also the kind of questions being asked in the forms they fill in, the language being used, and how they define disability.

Some people have a love-hate relationship with their impairments, which influence how they view themselves on a bad day. Some think they’re not worth declaring once they believe they’ve overcome them (stutterers fall into that category). Others find themselves sometimes declaring their disabilities, sometimes not – irrespective of whether they mean to or not – depending on the type of question being asked. (This has certainly been my experience as a deaf person.)

Whatever our attitudes, whatever we do to try to keep it to a minimum – ultimately it is people with disabilities and their carers who are having to deal with excess bureaucracy, thanks to the persistent ignorance that prevails in our society.

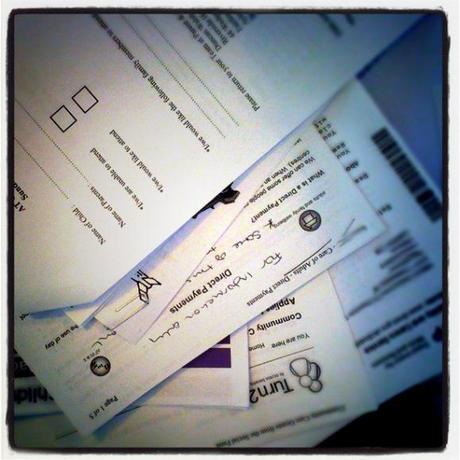

The amount of paperwork or correspondence I have had to address on Isobel’s behalf – particularly since her diagnosis – is staggering. DLA is just one aspect; I have also had to wade through oceans of paper and correspondence for direct payments, her SEN statement, emergency and care plans in childcare settings, and self-directed support. You would need a Phd to make sense of the language some of these contain.

In three years I have filled three box files with the following: clinical reports from paediatricians, neurologists, dietitians and therapists, hospital discharge papers, benefit award letters, activity goal sheets, rehab session records. Nursery registration forms and prospectuses, and papers relating to Child Benefit and Child Tax Credits make up just 10% of those files. I daren’t throw out any of it, lest I need it as evidence.

The bureaucracy that parents of non-disabled children experience is not a patch on this. It’s not right, either, all the time we spend on declaring our children’s disabilities to various authorities – despite DLA, which is meant to be our passport to the support that they need.

Just 16% of mothers with disabled children work, in contrast to 61% of other mothers. Indeed the income of families with disabled children average £15,270 – well below the UK mean of £19,968. Yet the costs of bringing up a disabled child are up to three times those of bringing up her non-disabled peers.

Even if these statistics don’t reflect the whole picture, they do clearly indicate the enormous amount of paid hours parents have to sacrifice for their disabled children. The daily care routine is just part of the story; we also have to account for hospital/therapy visits, rehab sessions, emergency stays, medical reviews and assessments.

(In Isobel’s first 18 months – when she was fitting regularly – 7-10 appointments a week was standard. They’re now down to 3-6 a week, most of which have to be accompanied by myself or Miles. Isobel’s nursery attendance this autumn is long overdue.)

We don’t need the bureaucracy as well.