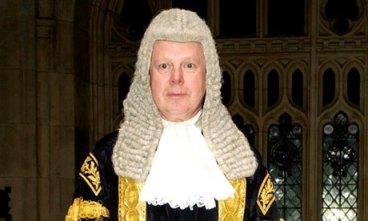

The news – although not yet officially announced – that Sir John Thomas is to succeed Lord Judge as lord chief justice of England and Wales shows how fallible some of us were in predicting that the job would go to Lady Justice Hallett.

So opens an article by Joshua Rozenberg announcing the selection of the person who is to preside over our judiciary, who will shape it and determine its future. I think he’s far too self-deprecating; if this decision shows the fallibility of anyone, it’s of the selection committee (made up of four white men and one white woman)  and the selection procedure.

and the selection procedure.

Perhaps as you read this you’ll be agreeing with a commenter under Rozenberg’s piece who wrote that, “The independent body in charge of judicial appointments seem to be serving their purpose” because ”Like with any job in any profession – the best person for it should be successful”. Now, I imagine no-one would disagree with the latter statement – but excuse me if I depart quite strongly from acquiescing with the first.

You see, no matter how much we try to dress it up as objective, as with nearly everything in life – including whether we thought sperm penetrated an egg or an egg enveloped a sperm – determining “the best person” for a job is a matter of qualitative judgment. And if there’s one thing studies of the qualitative – and often unspoken – criteria that determine hiring practices has shown, it’s that qualitative criteria discriminate against women.Why? For the very simple reason that women aren’t there already. This makes them an unknown quantity. They might want to do things differently. And who wants that?

Well, the judiciary actually. Within the selection criteria for the post of lord chief justice are the following requirements: “An understanding of the need for modernisation of the judicial system to deliver greater efficiency and effectiveness” and “Ability to lead change in encouraging a more diverse judiciary”. As you can probably imagine given the fact we’ve been given another white man to add to the list of white men, the latter is my favorite. And not just for irony klaxon purposes, but because it is simply a fact that a more diverse leadership leads to a more diverse workforce, for the reasons I discussed above. The judiciary has missed an opportunity to achieve one of its own stated criteria here.

But this is not to say that the former isn’t deeply relevant in its own way. The new lord chief justice is tasked with modernising the judicial system to deliver greater “effectiveness”. What does this mean? Presumably, given the ultimate aim of the system being, as the name suggests, to deliver justice, it means, to get better at doing that. It seems to be an admission that it’s not good enough. And they’re right. It’s not.

It’s not good enough for the, at a conservative estimate, 59,000 rape victims a year who don’t see justice. It’s not good enough for women who are still being disproportionately sentenced compared to men for non-violent crimes. It’s not good enough for women whose abusive husbands are being regularly awarded custody of children, because they are “good fathers“. These miscarriages of justice take place in the context of a legal system designed for and still largely executed by men.

Rozenberg writes that this appointment was always likely, “because, with most of the applicants being male, the chances that a woman will be the strongest candidate, judged by traditional criteria, are statistically small. Nobody wants to change those criteria.” I don’t know who the “Nobody” Rozenberg refers to is, but he doesn’t speak for me, and he doesn’t speak for the thousands of women who have been let down by the justice system. Our obsession with “merit” as if it’s some sort of objectively defined, tangible criteria that we can pick up and put down and all agree on is not only rubbish, it is an actively damaging and institutionally sexist, racist, and any other ist you care to think of, concept. Merit is culturally and socially defined. So, surprise surprise, if your culture is sexist, so will your definition of merit. Not only this, but the idea that gender is and even should be somehow irrelevant to determining merit is misguided (if I’m not being cynical). Sometimes, a woman will be the best woman for the job; this was one of those times.