Unlike Takao who is very much missed, Komurasaki is missed by no one. – a Yoshiwara courtesan, quoted in 1683

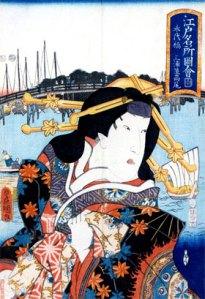

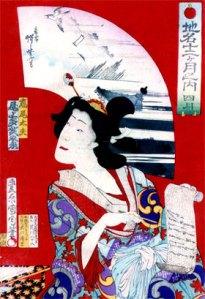

By now the regular reader should have noticed three recurring themes in my harlotographies: one of them pertains only to whores of pre-modern times; the second up to at least a century ago (though it is more pronounced in ancient stories); and the third up until the present day. Taking these in reverse order, they are as follows: the inability of amateurs to simply report biographical facts without embellishing, dramatizing and romanticizing them; the difficulty of ascertaining even numeric biographical details with any certainty; and the confusion of more than one harlot with the same name. All three principles are highly noticeable in the tale of Takao, a Japanese oiran (courtesan) who lived from 1640 to 1659; the lady in question was one of at least six courtesans (some sources say as high as eleven) with that name, and so is generally designated with the unimaginative moniker “Takao II”. Very little is known about her with any certainty other than the day of her death, December 5th, 1659; however, that didn’t stop talespinners from turning her story into one of the most popular of kabuki plays.

By now the regular reader should have noticed three recurring themes in my harlotographies: one of them pertains only to whores of pre-modern times; the second up to at least a century ago (though it is more pronounced in ancient stories); and the third up until the present day. Taking these in reverse order, they are as follows: the inability of amateurs to simply report biographical facts without embellishing, dramatizing and romanticizing them; the difficulty of ascertaining even numeric biographical details with any certainty; and the confusion of more than one harlot with the same name. All three principles are highly noticeable in the tale of Takao, a Japanese oiran (courtesan) who lived from 1640 to 1659; the lady in question was one of at least six courtesans (some sources say as high as eleven) with that name, and so is generally designated with the unimaginative moniker “Takao II”. Very little is known about her with any certainty other than the day of her death, December 5th, 1659; however, that didn’t stop talespinners from turning her story into one of the most popular of kabuki plays.

I’ve written at length about the world of the oiran, but this passage bears repeating:

Until 1617 prostitution was completely legal in Japan, but in that year the Tokugawa Shogunate issued an order restricting prostitution to certain areas on the outskirts of cities. Yujo (“women of pleasure”) were licensed and ranked according to an elaborate hierarchy, with oiran (courtesans) at the top and brothel girls (who were essentially slaves) at the bottom. These “red-light districts” were not implemented for the moralistic reasons which spurred their creation in the West, but rather to enforce taxation and keep out undesirables such as ronin (masterless samurai); prostitutes were also not allowed to leave the district except under certain rigidly-controlled circumstances. Soon the districts grew into self-contained towns which offered every kind of entertainment a man might want, all entirely run by women. Once a girl became a prostitute her birth-rank ceased to matter, and her status was determined by such factors as beauty, personality, intelligence, education and artistic skills. Even among the oiran there were ranks, of which the highest were the tayu, courtesans fit to entertain nobles…

Takao was a tayu under contract to the Great Miura, the largest brothel of the Yoshiwara district. Though we know absolutely nothing about her personality or skills, they must have been as striking as her beauty for her to achieve the position of “top girl” at the Miura house soon after her debut, and to become the most sought-after courtesan in Yoshiwara within a short time thereafter. Every contemporary source (of which there are three) say she died of tuberculosis; Takabyōbu kuda monogatari (Tales of Grumbling Otokodate) also states that several of Takao’s clients paid for her funeral even though they had failed to visit her on her deathbed. But despite “consumption” being the traditional cause of courtesan demise in Western romance, Takao’s tragic death at the peak of her success wasn’t nearly dramatic enough for kabuki; for that love, treachery and violent death needed to be added.

Enter Date Tsunamune, who had become Lord of Mutsu at the age of eighteen after the death of his father. Some of his kin, however, plotted against him and managed to trick him into visiting Yoshiwara as a means of getting him out of the way. While there he hired Takao and immediately fell in love with her, proposing to buy out her contract and marry her. This much is largely historical; Tsunamune was a real person whose did indeed face opposition from his family (and was deposed in 1660). He may indeed have visited Yoshiwara, though a letter claimed to be from Takao to him has been proven a nineteenth-century forgery. But the rest of the story as told for generations is the stuff of fiction. Naturally, Takao is supposed to have rejected his offer; some sources feel mere dislike for the man or a desire for independence after the termination of her contract are insufficient motivations for the rejection, and invent a lover who had pledged to marry her when her term of indenture was up. I’m sure y’all can guess where the story goes next: Tsunamune refused to take “no” for an answer and made the brothel owner an offer she couldn’t refuse, Takao’s weight in gold for the contract. The owner accepted, but took advantage of Tsunamune’s lust by putting iron weights into the sleeves of Takao’s robe, boosting her weight to 75 kilograms. Some storytellers say that on the boat trip from the brothel, Takao hurled herself into the river to drown, counting on the weights to take her to the bottom; others say Tsunamune caught her in the attempt and killed her with his sword instead, then dumped her body. Still another version says that Tsunamune had one of her fingers broken for every day she refused his bed, and after he had gone through both hands he had her hanged. But all of these say that her death (whether by murder or suicide) was the excuse used by Tsunamune’s uncle to remove him from power.

Enter Date Tsunamune, who had become Lord of Mutsu at the age of eighteen after the death of his father. Some of his kin, however, plotted against him and managed to trick him into visiting Yoshiwara as a means of getting him out of the way. While there he hired Takao and immediately fell in love with her, proposing to buy out her contract and marry her. This much is largely historical; Tsunamune was a real person whose did indeed face opposition from his family (and was deposed in 1660). He may indeed have visited Yoshiwara, though a letter claimed to be from Takao to him has been proven a nineteenth-century forgery. But the rest of the story as told for generations is the stuff of fiction. Naturally, Takao is supposed to have rejected his offer; some sources feel mere dislike for the man or a desire for independence after the termination of her contract are insufficient motivations for the rejection, and invent a lover who had pledged to marry her when her term of indenture was up. I’m sure y’all can guess where the story goes next: Tsunamune refused to take “no” for an answer and made the brothel owner an offer she couldn’t refuse, Takao’s weight in gold for the contract. The owner accepted, but took advantage of Tsunamune’s lust by putting iron weights into the sleeves of Takao’s robe, boosting her weight to 75 kilograms. Some storytellers say that on the boat trip from the brothel, Takao hurled herself into the river to drown, counting on the weights to take her to the bottom; others say Tsunamune caught her in the attempt and killed her with his sword instead, then dumped her body. Still another version says that Tsunamune had one of her fingers broken for every day she refused his bed, and after he had gone through both hands he had her hanged. But all of these say that her death (whether by murder or suicide) was the excuse used by Tsunamune’s uncle to remove him from power.

Co-opting the lives of sex workers to tell lurid stories of woe and tragedy is nothing new; it’s been done for centuries, perhaps millennia, and shows no signs of stopping anytime soon. But at least in the Japanese variety, the tragedy derives from the freely-chosen actions of a proud, accomplished woman in defiance of fate, rather than from the pathetic subjugation of a cookie-cutter victim stereotype. And I don’t think there’s any need to explain which I prefer.