It was one of those intensive design charettes examining the whole building early on. Lake/Flato Architects gathered the client, contractor, engineers, department heads and a student representative to collaborate on energy saving goals for the Arizona State University Polytechnic Academic District in Mesa, 30 miles southeast of Phoenix. Their challenge was to transform the decommissioned Williams Air Force Base and old army street into a friendly pedestrian campus of five new academic buildings that house labs and classrooms for sciences, engineering, math, technology and the performing arts.

Along with working within the migraine parameters of the drop dead budget, the primary consideration beat down on the stakeholders as they sipped hot coffee in the conference room: Shielding the brutal desert sun.

“The students are here in very hot months of the year so making a building that took advantage of milder climate was critical and we created a desert mall out of the old street with breezeways and big circulation spaces and lobbies that are very well shaded with cross ventilation,” recalls the firm’s co-founder, Ted Flato, adding that when it rains it rains “bucket loads” and stormwater is naturally collected in small dams in an amphitheater at the end of the mall. Flato recalls he was “hot off” of a family trip in Morocco and thought of Lyle Lovett’s lyrics to This Old Porch song about playing hide- and-seek from the hot August sun. He envisioned buildings that shaded outdoor spaces from low angle light, as well as perforated metal shading walls, windows and ceilings—materials like steel and concrete block that weather well in that harsh climate.

“So much of smart sustainability is not using fancy building systems but old ideas that have been around forever, and I thought about the streets of Marrakesh and shared photos of buildings tied together with narrow openings for the letting in the sun,” Flato says.

Thirty years earlier, the place for problem solvers to be was Yale, where student William McDonough was informed solar power had no place in architecture. It took three decades for architects to travel from Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome at Expo’67 in Montreal to the EPA’s Energy Star ratings of 1992 and the U.S. Green Building Council’s incentive-building Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program in 1998. The years between Silent Spring and Cadillac Desert witnessed the construction of some of the greatest resource-consuming buildings of all time along with an unparalleled output of greenhouse gases.

The Current Climate

Today, there’s a compelling incentive to strive for Net Zero energy, the highest possible state of grid independence. In what has emerged a second industrial revolution, architects are not just circumventing red tape but shifting the paradigm. Platinum and gold LEED certificates mounted in post-recycled, glass curtained lobbies and showcased on firm websites are badges of honor in the age of sustainability.

“LEED was devised as a reward system, a threshold to motivate both clients and architects to consider the environment,” says San Francisco healthcare architect Steve Nielsen, who attended SciArch in the '70s when the modern movement was abandoned in favor of the pursuit of creating new fanciful design. “To be truly evolutionary, architecture must have a positive effect on future generations, so it’s not just about the green building but sharing the thought process from which others can learn.”

Sustainability issues incorporated by the few during the first energy crisis were added to team planning agendas industrywide in the early 1990s, including brainstorming sessions for the greening of the White House, the Grand Canyon, and the Pentagon.

“The beauty of LEED is that to get the system going, architects are supposed to have early meetings to get input from everyone involved,” says Flato. “Not all items on the checklist are critical to making an energy-safe building and a high-rated building doesn’t mean it performs as well as it ought to and some non-rated buildings may perform better. But LEED is constantly evolving and is the best common language we have and clients are embracing it and wanting to get a good LEED grade.”

Lake/Flato clearly made the grade along with associate firm RSP Architects for the five high performance LEED Gold-rated buildings and four landscaped courtyards linked by a series of portals and arcades comprising the Arizona State University Polytechnic campus. Easily surpassing the silver rating it first sought, the project was highlighted as one of the Top Ten Green Projects of 2012 awarded by the American Institute of Architecture (AIA) in its Committee on the Environment (COTE) as featured in Dwell. This was the fourth top AIA green prize awarded to Lake Flato, a firm that has earned 43 national design awards.

It’s no accident that green pioneers Flato and his partner, David Lake, were among the minority sensitive to environmental issues in the '70s when others got lost in style, making pretty buildings but not always thoughtful ones. While the term “sustainable” was not part of their language in 1984 when they founded their firm in San Antonio, Texas, their main objective was to be connected to the outdoors in designing buildings inspired by Louis Kahn’s simple organization of service, circulation, public and private use. “Simple organization is hard to achieve but ultimately makes really great buildings,” adds Flato.

The employment of modern logic when building new green machines is apparent in most significant sustainable buildings of recent years.

Projects of Note

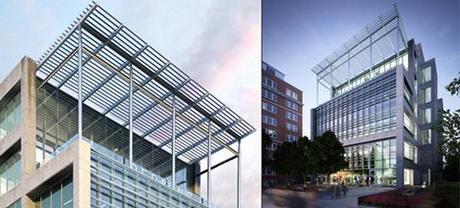

Perkins+Will for 1315 Peachtree Street in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo via Perkins+Will

Perkins+ Will for 1315 Peachtree Street in Atlanta, a civic-focused adaptive reuse of 1986 structure into a living lab and education tool for sustainable design, retaining much structure while optimizing exterior glazing, HVAC, water and lighting;

BDIM’s Iowa Utilities Board Office of Consumer Advocate Office Building in Des Moines. Photo via Baker Group

BDIM’s Iowa Utilities Board Office of Consumer Advocate Office Building in Des Moines on six acres of former landfill, capturing 100% of the stormwater from the average rainfall and using thermal mass capturing free heating and modulating temperatures with 68% energy savings in the first year;

Hennebery Eddy Architects for the Portland Community College (PCC) Newberg Center. Photo via Inhabitat

And Hennebery Eddy Architects for the Portland Community College (PCC) Newberg Center, the first net zero energy, higher education building in the state supporting the school’s mission to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050, reducing water use by 49.2% through low-flow faucets and toilets, a weather-based system reducing irrigation water 50% and taking advantage of the NW climate by incorporating ventilation and passive cooling via ventilation stacks organizing the circulation spine.

Newberg Center in Portland, Oregon. Photo via ECOBUILDING Pulse

Portland’s Newberg Center is yet another example of architects tapping both old strategies and new processes to achieve green. “An old barn in this region would have cupolas on the roof to allow heat to escape and we have a similar concept with ventilation stacks to let heat move out with natural ventilation, mixed with new technology to monitor the C02 in the classroom to determine if more fresh air is needed and using a mechanical system to provide that,” says Erica Dunn, an associate at Hennebery Eddy who led the two year project.

Dunn admits reaching net zero is a tall order requiring an intense integrate process which boosted her knowledge of mechanical and electrical engineering functions to achieve designs such as a patterned glass curtain wall with movement framing the mountains in the entryway and vacancy centers for smart lights that shut off automatically when occupants leave a room. “It’s about combining passive systems with highly efficient mechanical and electric systems that help the building perform as efficiently as possible,” she says.

Genius Building

Beyond the smart building in reflecting architecture’s accelerated I.Q. is the genius building. It doesn’t merely react to conditions, but learns from the environment and predicts those conditions to adjust and passively cool, heat and light a space rather than using energy. Such genius is exemplified by NASA’s first sustainable space station on earth by William McDonough + Partners. One of the most densely instrumented buildings in the world, it is already in use by Lawrence Labs as a test bed for technology systems and integrated predictive building controls such as Nano sensors to monitor surfaces.

“If we show by example this can be done then people have models and this is why the sustainable NASA base has so much value,” says David Johnson, AIA, founding member of the firm’s San Francisco studio. Johnson says his colleague McDonough has provided tremendous leadership since teaming with German chemist Michael Braungart in 2002 on the Cradle to Cradle design theory.

The firm, with offices in Charlottesville, Va. and San Francisco, has helped create an industrywide standard by pushing the envelope with international projects such as the NASA Sustainability Base, the UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay, Park 20/20 work and recreation complex in The Netherlands and the ongoing master plan for consolidating operations of San Francisco’s Recology trash disposal by increasing the diversion of material from landfills from the current 80% to zero waste.

Green Is Healthy

A healthier outcome for future generations was also at the core of the new UCSF Mission Bay hospital for treating women and children with cancer as architects from McDonough and Anshen &Allen worked at a high level with DPR Contractors to achieve the client’s stated goals for healthcare reform: Improving the physical facility to cut costs and improve patient outcome rather than focusing on operations.

“We looked at removing carcinogens, antigen disruptors and toxic materials used in small quantities from the patients’ space,” says Johnson. “Taking known carcinogens out of cancer wards was a novel thought in the competition for the project.”

Prior practices in sustainable healthcare ignored the hospital structure as a critical factor. This piece was added by Derek Parker and the Fable Hospital 2.0, an imaginary amalgam of design innovations published in 2004. It linked evidence-based medicine and evidence-based design, showing green building innovations may cost more in the beginning but soon reduce costs and increase revenues, music to the ears of boards and CEO’s. “The punch line is everything we know that can improve patient outcome has a payback period of seven years, and if you are building a 50-year hospital, it’s a no brainer,” Johnson adds.

The payback in energy savings has crossed over to residential design, where homeowners have made the leap from lowering utility bills with solar panels to supporting cutting edge net-zero designs such as the Full Plane Houses debuting in Oregon and Seattle.

Accessible Sustainability

A rendering of the JRA Green House in Portland, Oregon by the firm Departure.

The 1,950 square-foot Portland-based JRA Green House by the firm Departure achieves net-zero water usage through an 11,000 gallon potable water cistern underneath the carport. Other forward features include composting toilets, stormwater catchment, and complete gray water processing, along with innovative landscaping. A double-wall system filled with nearly 12 inches of cellulose insulation is supported by a five-kilowatt photovoltaic system, greatly reducing energy needs.

All of the options, including FSC-certified lumber and plywood sourced by Sustainable Norwest Wood, forge a house with ideally more energy production than consumption. Its owner, James Arnold, says these homes can be built at or below typical custom home costs by adhering stringently to an integrated design process and securing energy incentives. Portland architect Erica Dunn, a recent visitor to the Full Plane home, agrees that getting sub-contractors on board early on makes it possible to realize the vision.

“Primarily what you see in residential is the mechanical and electrical systems design-built by sub-contractors, and you need to select a contractor to get those people invested and to the table early in the design process,” says Dunn. “This way they can understand that with sustainable buildings you are using systems some have never used before and discussing how they work as complete rather than isolated systems means you can install them at a better rate and meet the client’s budget.”

When it comes to budget, the HOUZE zero-energy homes in the historic district of Houston are marketed as affordable alternative living, a concept defying the notion that only the super-rich can finance sophisticated green projects gracing the covers of magazines. Powered by 100% clean natural gas and game changing Power Cells, the passive homes are custom built with the buyer selecting the design and lot and getting pre-approved for financing.

Similar projects are being developed as green case studies in Rainier Vista, a mixed-income housing development in Seattle. A four-home micro-community by Dwell Development (which will grow to 15 units) exemplifies 5-star green building and design at an accessible price point. The units ranging from 1,350 to 1,850 square feet flaunt all of the sexy features of million dollar designs at less than half the cost: rain barrels, rooftop gardens, heat recovery ventilators, triple pane windows, whole home radiant systems, pine flooring recycled from telephone poles, recycled glass countertops and factory framed wall panels to reduce waste.

These affordable passive homes have the power to alter the image of the U.S. as a zealous energy hog, devouring about 40 percent of the world’s total energy, 25 percent of its wood harvest and 16 percent of its water. Since erecting and demolishing structures accounts for some 40 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas creation, sustainable architecture is doing its part to slow global climate change, rejecting hungry mechanical systems of the past and embracing design theory and literature produced by a growing, anti-consumption movement linking buildings and the ambient environment.

The Road Ahead

“I’m glad green is hip and cool because it needs to be popular for us to be healthy,” says Flato, adding architects typically eschew popular trends. “People are sharing materials and a million things we didn’t have before.”

That sharing to achieve sustainable design goals is now essential to any project, according to Dunn. “We have a wide range of projects and clients but it is a non-negotiable item no matter the type or scale.”

Johnson warns architects who still have much to discover must address global issues with all of the vigor they have.

“As we sit in the San Francisco urban environment reading literature that is globally significant and head towards a population of nine billion, we imagine a world of ten billion and think about the urbanization and rising of the middle class in the developing world and how do we use our resources effectively for that many people?” he ponders. “We’ve just started. We’re just learning. This is forever.”