If you’ve listened to In the Dark or watched Wrong Man on the Starz channel, you either came away convinced that Curtis Flowers didn’t kill four people in cold blood back in 1996 or you weren’t paying attention.

Actually, In the Dark hasn’t weighed in on the guilt-innocence issue (that’s not what they do), but their careful dissection of DA Doug Evans’ case against Flowers has left the case in a shambles. If, hypothetically, the In the Dark team was charged with defending Curtis in a seventh trial even an all-white jury selected entirely of Winona residents couldn’t find him guilty.

Wrong Man presented us with a small group of criminal justice professionals who started out believing that Curtis was probably the killer. By the end of the two episodes devoted to the Flowers case, they had all abandoned Curtis as a suspect.

So, if Curtis didn’t do this terrible deed, who did?

Wrong Man leans tentatively fingers Doyle Simpson as the prime suspect. As I argue in the course of the program, Simpson seemed to be bending over backwards to let the world know that a gun had been stolen from his car in the parking lot of the garment factory where he worked. So, maybe Curtis didn’t steal the gun after all. Maybe Doyle did the deed and reported his gun stolen to throw everyone off the scent.

And maybe his girlfriend, Katherine Snow, told the authorities that she saw Curtis leaning up against Doyle Simpson’s car because that’s what investigators wanted to hear. But maybe she didn’t see anyone at all.

And why did Doyle’s brother, Emmett, run from law enforcement when they came to question him on the morning of the crime? Maybe he and Doyle were co-perpetrators.

Maybe. But, just like Curtis Flowers, Doyle Simpson fails the motive test. Sure, he had worked at Tardy’s in the past. And, unlike Curtis, Doyle had more than a passing acquaintance with organized crime (a mobster once left him for dead in a field outside of New Orleans). But that doesn’t make Doyle a cold killer. Prior to his death, Doyle came across as a passive man working hard to stay out of trouble.

Whoever killed four innocent people in the Tardy Furniture store on that fateful day in 1996 was familiar with armed violence and kind of liked it. No one was going to all that trouble over the approximately $400 investigators say was in the till that morning. (Although that figure is, at best, an educated guess.)

Episode 10 of the In the Dark Podcast was largely dedicated to the strange case of Willie James Hemphill, a local bad boy with a violent streak who was continually getting cross-ways with the law. It took the In the Dark team a full year to track Hemphill down in an Indianapolis courtroom (he’s still getting into trouble).

Law enforcement clearly saw Hemphill as a prime suspect. Relatives were alarmed to see a swarm of police cars descending on their homes in search of Willie James. Afraid that he would be shot on sight if he didn’t surrender, Hemphill turned himself in at the local police station (wearing Grant Hill Fila’s, the shoes investigators had linked to a bloody footprint at the crime scene) and was immediately handcuffed and booked into the local lock-up.

If it hadn’t been for a single slip of paper in the prosecutor’s file with Willie James Hemphill’s name on it, the In the Dark squad wouldn’t have known about the man. Even so, they had to wade through a stack of rat-eaten files stored in an abandoned factory to realize he had been booked into jail.

In the Dark, episode 10, makes it clear that the prosecution committed what is called a Brady violation by failing to inform defense counsel that Hemphill had been a suspect early in the investigation. That discovery will very likely win Curtis a new trial, but it doesn’t necessarily finger the new guy as the killer.

Hemphill says he was in Memphis on the day of the murder and his alibi might check out. But his demeanor when approached by In the Dark investigative reporters was consistent with innocence. He freely admitted that he had been a suspect and even says that, although innocent, he would have made a more convincing suspect than Curtis.

Hemphill certainly sounds like a career criminal who is fully capable of committing violence; but he doesn’t come off as a psychopathic killer–and whoever did the deed at the Tardy furniture store was either a hired killer (or killers) or enjoyed killing people for kicks.

As the investigators interviewed for the Wrong Man episodes on Flowers point out, the family members of the victims should have been considered suspects until evidence suggested otherwise. That’s just standard procedure. That said, I don’t see a compelling motive, and none of these people is any more capable of pulling off an outrage on this scale than poor Curtis Flowers. It was either a paid hit on a single individual that went bad when other employees entered the room, or the awful deed was done for the hell of it.

That brings us to a theory that has been explored extensively by some of the folks currently representing Mr. Flowers, the individuals I reference as “the Birmingham boys”.

Each victim of the July 16, 1996 murders was murdered execution style—one or two bullets to the back of the head. The presence of live ammunition on the floor suggested that one of the killers was using a 380 pistol that jammed repeatedly.

Nine days later, on July 25, 1996, the bodies of two innocent people were discovered in a pawn shop in Birmingham, Alabama. Each victim had been murdered execution style—one or two bullets to the back of the head. A surveillance camera revealed that the killer was wielding a 380 pistol that jammed repeatedly.

Winona, Mississippi lies three hours west of Birmingham on Highway 82. Steven McKenzie, the driver of the getaway car in the pawn shop murders, was arrested on August 1 in his hometown of Boston, Massachusetts. The shooter, Marcus Presley (16) and his accomplice, Lasamuel Gamble (18) were arrested in Norfolk, Virginia on August 9, 1996 after two weeks on the run.

That same day, Horace Wayne Miller, a lieutenant with the Mississippi Highway patrol, asked Norfolk officials to keep him apprised of their investigation.

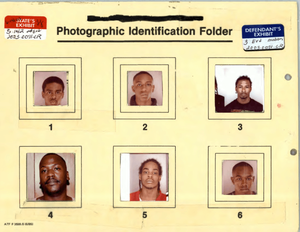

Two weeks later, a picture of Marcus Presley, the shooter in the Birmingham murders, was included in a photo array shown to Porky Collins, a witness in the Winona, Mississippi case.

On November 16, 2015, Marcus Presley signed an affidavit claiming that Lasamuel Gamble and Steven McKenzie (the driver of the getaway car) had been in Mississippi the day of the Winona murders and had returned with several hundred dollars in their pockets after claiming to have “hit a lick” (committed a crime).

A shoeprint in a pool of blood found in the Winona furniture store was found to be from a Grant Hill Fila shoe—the footwear Gamble, McKenzie (and just about every other young man in America) was wearing while in Mississippi.

Can Marcus Presley’s affidavit be trusted? Yes and no.

Courtroom testimony shows that Presley was the shooter in the pawn shop murders in Birmingham even though, prior to being shown video of the crime, he insisted that Gamble had been the gunman. If Gamble and McKenzie were in Mississippi the day of the Winona murders it’s very possible that Presley was with them.

Between June 19th, 1996 and June 30th of that year, Presley was involved in five robberies at gunpoint. In the course of these crimes, one employee was shot in the leg and another in the back (both survived) and Presley was the shooter in both cases.

Presley and Gamble did four of the June heists together and one crime was perpetrated by Presley alone. Although Presley was only sixteen, he seems to have been the driving force behind these crimes. Gamble never discharged his weapon.

Presley and Gamble had developed a simple modus operandi. Store employees were threatened with death and forced to lie on the floor. While Presley drove the action, Gamble kept his gun trained on the scene in case anyone tried to flee. After the second stick up, the two men argued about whether they should have killed the witness.

Evidence suggests that Marcus Presley was a psychopath who enjoyed random violence for its own sake.

Presley and Gamble made three runs to Boston during the summer of 1996: once after their June crime spree, once after the pawn shop murders and once immediately after the furniture store murders in Winona. Their pattern was to spend a week or so lying low before going on another rampage. The two men had family in both Boston and Norfolk.

District Attorney Doug Evans argues that Flowers, enraged with losing his job, stole a gun out of a parked car at the Angelica garment factory, cooled his heels at home for an hour or so, then marched to the furniture store with murder in his eye, did the foul deed, and raced home.

But how could a single person (especially a man like Curtis Flowers) dispatch four victims with a bullet to the back of the head? The crime had a random and senseless quality to it. It takes no imagination at all to imagine Marcus Presley committing a crime like that–we have the video from the pawn shop.

Curtis Flowers was raised in a loving home by a gospel-singing father and a mother known for her culinary and entrepreneurial abilities. Marcus Presley and Lasamuel Gamble weren’t raised at all. Both men bounced from one traumatic living arrangement to another with no respite. Whoever killed the four victims in Winona was beset by demons. Curtis Flowers, as any prison guard who has ever worked with him can tell you, has no demons.

So, if I am forced to pick an alternative perpetrator in this awful case I would lean toward the Birmingham Boys, Presley in particular.

But it isn’t necessary to prove a case against any of these people; the real scandal is that the existence of alternative suspects was systematically withheld from defense counsel.

And why didn’t DA Doug Evans even consider the Presley-Gamble connection?

By the time Presley and Gamble were arrested, Doug Evans wasn’t interested in alternative scenarios; he “knew” Curtis was the killer.

Then why haven’t the defense attorneys who have represented Mr. Flowers through six trials present Presley and Gamble as an alternative theory of the crime?

Because Mr. Evans didn’t tell them about the Alabama connection. It was his legal obligation, but it’s easy to see why he didn’t. Evans didn’t want jurors comparing his tortured theory with a simple and sensible alternative.

In other words, Evans committed two egregious Brady violations that will, in the days that lie ahead, force the courts to grant a new trial and, just as likely, insist that Doug Evans recuse himself from this case.

That might not be so if the whole world wasn’t watching, but it is. Sure, once In the Dark is over the heat will diminish slightly. But if Curtis Flowers doesn’t get relief in the face of these well-publicized facts there will be hell to pay. Injustice flourishes in the darkness, and the sun is now blazing in the heavens (at least for Curtis Flowers).