Balthus

I peered into the disquieting world of Balthus last week. A collection of his works is gathered in Vienna, which seems particularly fitting to me, knowing him to be a lifelong favorite of and inspiration to Francis Giacco, who is a role model of mine and one-time inhabitant of fair Vienna. Giacco paints dreamy still-lives dappled with fractured afternoon sunlight, layering patterns upon patterns in a quietly hypnotic fashion, the arrangements comprised of treasures gathered in Europe—musical instruments, luscious woven fabrics, curious marionettes, and globes that revolve and ache with Fernweh. His predilection for Balthus filled me with extra keenness to discover some hidden secrets.

Balthus

And Balthus is shrouded in secrecy. I once encountered a book on him, a picture-heavy volume that began with an anecdote that Balthus preferred an artist statement along the lines of: ‘Balthus is a painter. No one knows anything about him.’ On reading these lines, I felt to continue reading the book would amount to painterly betrayal; I feasted only on the pictures. And when I finally met him face-to-face at this exhibition, I honoured his wishes and ignored the copious text printed on the walls of the Kunstforum. I can’t tell you anything about Balthus; I even forgot to check where he is from. But isn’t that a wonderful thing?—To talk, rather, about his paintings.

Balthus

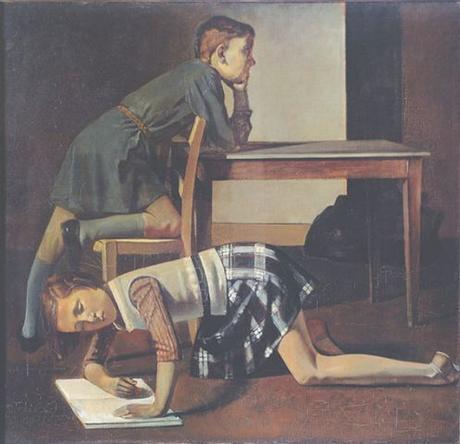

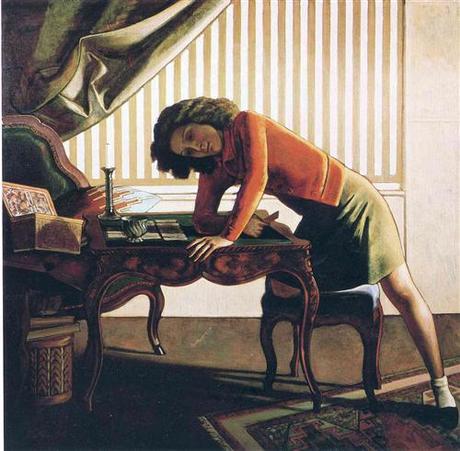

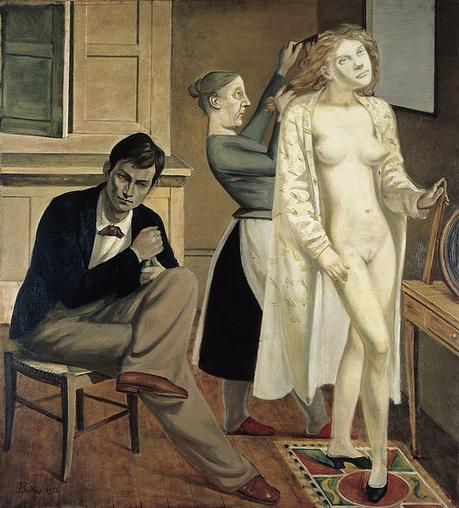

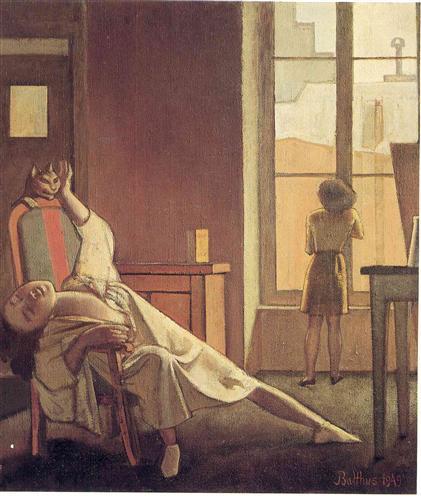

His paintings cloak the rooms in an overwhelmingly sinister atmosphere. This is surprising, given their apparent simplicity, their bold, clear, often flattened shapes, their often very plain subject matter: children loafing about, unpretentious portraits, still lives. How can such simple imagery fill one with such a sense of dread, leave one so unsettled? Perhaps it is the quiet implications: the tense and inappropriate relation of girl to boy; the gutting disinterest of men in their wives; the invitation to see just a little too far up a little girl’s dress; the huge knife thrust menacingly through the loaf of bread. And the evil cats, perched like demons above melodramatically exuberant figures. One feels oppressed in these rooms, for Balthus alone is not to blame: we are complicit in his quiet evils because we fail to avert our eyes.

Balthus

And why can’t we look away? I think it is something to do with how formally strong the paintings are. Shapes are pieced together firmly; arcs swing through figures and drive our gaze forcefully. People are reassuringly geometric: strong, balanced and mathematically pleasing. But the flatness is deceptive—foreshortened arms reveal Balthus’ understanding of space, but deliberate curvature of it. He shatters the picture plane with tables bent into conflicting perspectives; he plays with proportions and mocks our sense of sight, subduing it to his own dark purposes.

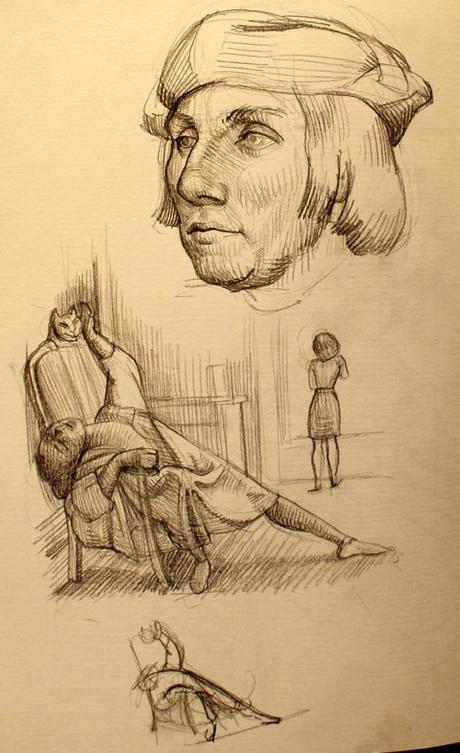

The drawing in the paintings is usually firm, calculated and assured. This confidence is beguiling. The apparent simplicity of the paintings is really supported by intelligent, knowledge-laden lines, surreptitiously used with purpose. We are enchanted by the result, but the structure beneath is carefully planned and artfully disguised. I think Balthus’ drawing, though not aiming at naturalism, is not as naive and simple as it seems. This is why the paintings strike us so forcefully.

Balthus

And then there is the paint. Balthus’ surfaces are often rough, paint viciously scrubbed on, the pock-marks gleefully disturbing the pictorial flatness. This dimension cannot be overstated when describing Balthus’ painting: otherwise low-contrast, neutral colours—as in his landscapes—which gently merge and ripple, are simultaneously hacked as if from the inside thanks to this many-layered scumbling. ‘The idea of a layered process is celebrated and the opticality of the surface is animated by a lively push and pull at the scale of the weave’ (Nelson, 2010: 156). This rough manner of applying paint works its own quiet effect on the viewer in unison with the content of the image and with the careful construction of it. Balthus gives the paint itself a voice, and it is a coarse, goading one, just as provocative as the cats and the knives and the underage girls.

Copy after Balthus with bonus Holbein

I think an important key to Balthus is the possibility of friendship with children. This is a very delicate subject, fraught with predatory dangers. And yet, on the flip side, there is some sort of violence we wreak on children when we oppress them for their rational deficiencies. Children are not fully rational, but nor are they completely ignorant, and certainly not innocent. Meeting children on a more level footing involves acknowledging their evils, and permitting them the space for self-determination. It is a desperately lonely feeling as a child to feel that you know yourself, that you have independent thoughts, and yet you are an outsider to the world of decision-making; you are an observer of your own life. And yet, perhaps this childhood solitude is just what Balthus wrenches us back to, as Rilke (1997: 41-42). writes:

‘Aber vielleicht sind das gerade die Stunden, wo die Einsamkeit wächst; denn ihr Wachsen ist schmerzhaft wie das Wachsen der Knaben und traurig wie der Anfang der Frühlinge. Aber das darf Sie nicht irre machen. Was not tut, ist doch nur dieses: Einsamkeit, große innere Einsamkeit. In-sich-Gehen und stundenlang niemandem begegnen,—das muß man erreichen können. Einsam sein, wie man als Kind einsam war, als die Erwachsenen umhergingen, mit Dingen verflochten, die wichtig und groß schienen, weil die Großen so geschäftig aussahen und weil man von ihrem Tun nichts begriff.’

(‘But perhaps these are the very hours during which solitude grows; for its growing is painful as the growing of boys and sad as the beginning of spring. But that must not confuse you. What is necessary, after all, is only this: solitude, vast inner solitude. To walk inside yourself and meet no one for hours—that is what you must be able to attain. To be solitary as you were when you were a child, when the grownups walked around involved with matters that seemed large and important because they looked so busy and because you didn’t understand a thing about what they were doing.’)

Seeing eye-to-eye with children and their simple but nonetheless penetrating sorrows is probably what is required to truly befriend them. I suspect few people really befriend children, preferring rather to look down on them, talk down to them, and consider their inferiority endearing, their companionship like that of a stupidly loveable dog. Balthus intimates that children are more like cats: crafty and guileful, if at our adult disposal. And Balthus disconcerts us by coaxing us into the secret world of childhood, inviting us to converse with children as equals. I think of Gurdweill’s unfussy interactions with children in David Vogel’s (2013 [1930]: 93-94) novel:

‘Gurdweill stood up to leave. He pinched Fritzi on his smooth, fat cheek; the baby cupped Gurdweill’s nose in his clumsy hand; and an alliance was cemented between them. … And now he had a new friend: little Fritzi!’

But perhaps such friendships are themselves a fantasy, being by definition imbalanced, and requiring some artificiality on the part of the adult. Perhaps it is this very imbalance that Balthus disquiets us with. He leaves us feeling that such friendships are, after all, unnatural, and inevitably shadowed by dread and secrecy.

Balthus

‘How do we then progress

to a ‘childlike wisdom’

in this confusing universe

of impossible electrons,

without completely

reverting back to

childhood?’

(Jacques Pienaar)

Nelson, Robert. 2010. The visual language of painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. 1997. Briefe an einen jungen Dichter / Briefe an eine unge Frau. Diogenes: Zürich.

Vogel, David. 2013 [1930]. Married life. Trans. Dalya Bilu. Scribe: Melbourne.