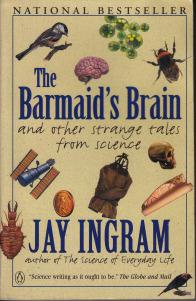

Science requires translation. Even very intelligent people in other fields of study have trouble understanding what scientists have been saying. That’s why science writers are so important. They can distill the heady knowledge that empirical method produces into a palatable tipple for the laity. Jay Ingram’s The Barmaid’s Brain is one such digestible report. As the subtitle (And Other Strange Tales from Science) indicates, this book is about the weird world of science’s often hidden charms. We all pretty much know that quantum mechanics has turned conventional wisdom on its head. We also know (courtesy of the media) that science and religion fight like cats and dogs. What we don’t see is that scientists often disagree on how to interpret data, particularly on the weird end of things. Ingram tells many such interesting tales from nature, psychology, and technology.

Science requires translation. Even very intelligent people in other fields of study have trouble understanding what scientists have been saying. That’s why science writers are so important. They can distill the heady knowledge that empirical method produces into a palatable tipple for the laity. Jay Ingram’s The Barmaid’s Brain is one such digestible report. As the subtitle (And Other Strange Tales from Science) indicates, this book is about the weird world of science’s often hidden charms. We all pretty much know that quantum mechanics has turned conventional wisdom on its head. We also know (courtesy of the media) that science and religion fight like cats and dogs. What we don’t see is that scientists often disagree on how to interpret data, particularly on the weird end of things. Ingram tells many such interesting tales from nature, psychology, and technology.

The essays in the book are loosely grouped into areas with some common theme. The psychology story that struck me as being particularly appropriate for this blog was the one about Joan of Arc. Joan, as most of us learned from history, was a prodigy. Illiterate, female, and poor, she nevertheless displayed a military genius that led her to the head of a French army trying to hold off the advances of the English. When turned over to the enemy she was treated as a witch, tried for heresy, and burned at the stake. Later she became a saint. The reason that she’s in a book of science essays is that Ingram wonders what exactly was going on when she heard voices and saw visions. Neuroscientists have devised ways of peering into the brain during religious experiences, and psychologists have constructed theories of why otherwise sane people hear voices. Joan doesn’t fit into the category that used to be called schizophrenia, nor does she appear to have been in any way insane. She was religious and her religion spoke to her.

When I was growing up, it wasn’t unusual for scientists to be believers. Nothing was wrong with believing in a god and studying the physical world. Indeed, the idea went back to Isaac Newton and other scientists of the first generation of the Enlightenment. Implications eventually led to the utter absence of deity from the world. People such as Joan were understood as sadly misled by a religion that could not be distinguished from magic. Yet Joan, as Ingram well knows, would hardly be a household name without her visions and her faith. At the end of the analysis, Joan rises from the couch still a mystery. An enigma to science, and suspect to many religious. She was, it seems to me, quintessentially human. We are all, it seems, whether saints or scientists, subject to what empirical evidence will allow us to believe. Most of the time, anyway.