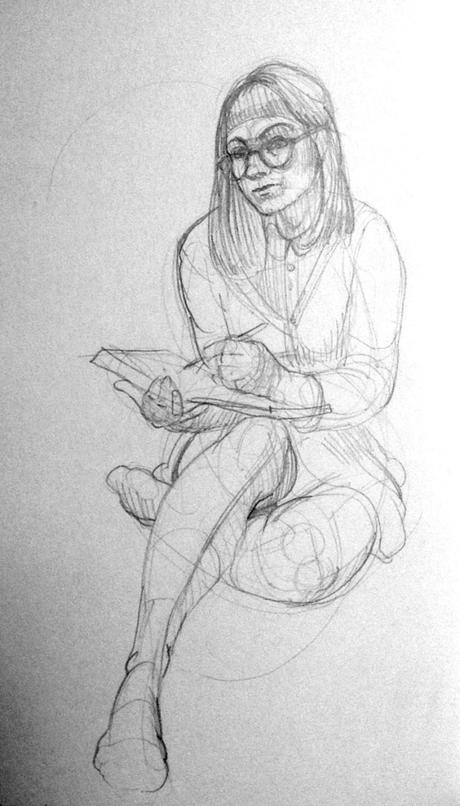

The decision (c) Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

In his eminently readable paper, ‘How I see philosophy’ (collected in the book of the same name), Friedrich Waismann urges us on to the dizzying thrill of the questions that originally brought our buzzing, inquisitive minds to philosophy. His plea perhaps grows increasingly relevant as philosophy becomes more analytically constrained, as the scientific project and its quest for order and explanation and proof creeps into all spheres of our lives, as ordinary people demand answers that ring with the clarity of science. Waismann makes a plea for the fog, for the roving unrest it stirs in us, for the rabbit holes it leads us down and the impassioned discussions it gives rise to. ‘The genius of the philosopher,’ asserts Waismann (1968: 16) ‘shows itself nowhere more strikingly than in the new kind of question he brings into the world. What distinguishes him and gives him his place is the passion of questioning.’ And yet further: ‘There is nothing like clear thinking to protect one from making discoveries’ (Waismann, 1968: 16).

This is not to decry reason and to rally behind an unthinking mental anarchy. Quite the opposite. It is to stimulate original thought, to pursue reason wherever she may lead, away from convention if she must, out of habits, disrupting prejudices (Waismann, 1968: 32). It is to remember why we started–we and our compatriots in thought, all the way back to Plato–quite simply: wonder (Waismann, 1968: 3). Waismann (1968: 16) urges us, as we flounder in the heady haze of brain-breaking wonderment, to take heart that ‘some of the greatest discoveries have even emerged from a sort of primordial fog.’ The ‘clarity neurosis’ will not furnish us with solutions, but only with the appearance of them. Clarity is reassuring, it gives us no reason to challenge the well-worn groove we circle around in, and for that very reason it extinguishes our creative spark before it gets a chance to warm up.

Waismann does not champion confusion. Rather, he sees philosophy as having a different aim than science (Waismann, 1968: 34). He reflects on a tradition grounded in Descartes and Spinoza, in which precise definitions, like quanta of knowledge, stack up—Lego-like—into tight axioms, by which we can deductively prove that the finite and infinite substances and all their attributes are none other than God himself, Q.E.D. (Spinoza, 1677). Such a logical project is admirable in its ambition, noble in its intentions. And Descartes (1997 [1637]: 7), after all, would not force his method on us (‘Es ist also nicht meine Absicht, hier die Methode zu lehren, die jeder befolgen muß, um seinen Verstand richtig zu leiten, sondern nur aufzuzeigen, wie ich versucht habe, den meinen zu leiten’—‘It is not my intention here to teach the methods that everyone must follow in order to correctly guide his reason, rather to demonstrate how I have tried to guide my own’). No, Waismann (1968: 20) does not seek confusion, but he does call for a change of outlook, defiantly declaring in the face of all this elegant reasoning that ‘insight cannot be lodged in a theorem.’

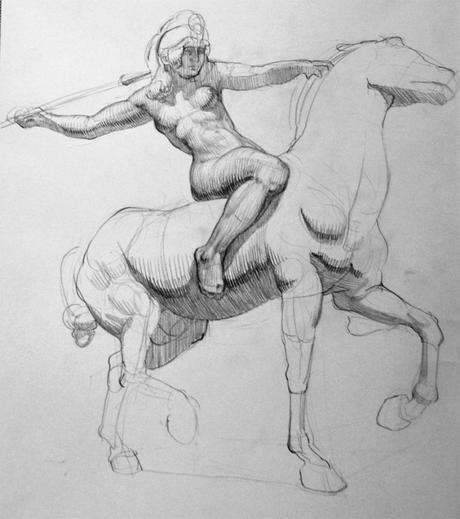

Franz von Stuck, Amazone (copy after sculpture)

Insight! When we had hoped for answers and airtight proofs, Waismann leads us back to the questions in order redefine the essence and purpose of philosophy. And the essential feature, he (Waismann, 1968: 32) argues, is vision. A philosopher is not a builder of systems, but an agile thinker who cannot help but challenge our accepted modes of thought. She takes nothing for granted, and takes everything in with the same open-eyed amazement as a child, with the same persistent ‘why’ dogging every new piece of knowledge she encounters. She keeps a level head in that primordial fog, and, says Waismann (1968: 10), if she reframes the troubling question she might just ‘dissolve’ rather than ‘solve’ it. But this, he adds, would be a meagre and negative task for philosophy, to simply dispel fogs. No, the positive task for philosophy, he (Waismann, 1968: 21) argues, ‘what is essential in philosophy, is the breaking through to a deeper insight.’ And the purpose, far from satisfying us, is to keep us ruffled and amazed: ‘to open our eyes’ (Waismann, 1968: 21).

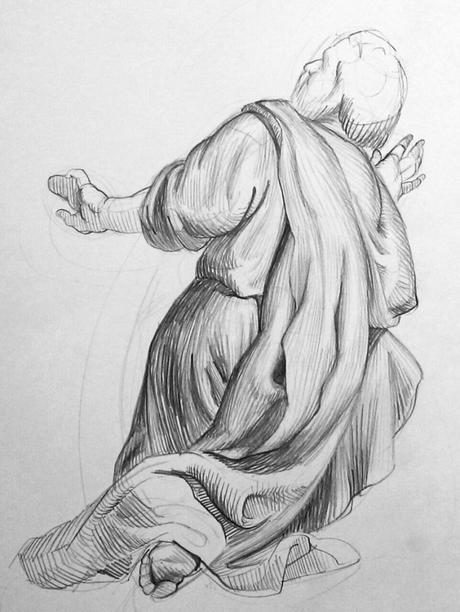

Rubens, Venusfest

What Waismann calls for is an attentive outlook that is willing to look at things sideways, to chew them over backwards, and to act in a creative manner. A search for answers already makes a fatal assumption. I am reminded of the notoriously inquisitive physicist, Dr Jacques Pienaar, who guilelessly prefaces his papers with such opening statements as, ‘In order to solve the problem of quantum gravity, we first need to pose the problem.’ This is the hallmark of the born philosopher: ‘the passion of questioning’ is in his blood. He navigates the fog not in order to obscure, not in order to destroy, but because of an insatiable sense of wonder backed up by the courage to cast a discerning eye over all intellectual territory. Emerson’s (1847: ‘Self-reliance’) words echo in Waismann’s: ‘Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist. He who would gather immortal palms must not be hindered by the name of goodness, but must explore if it be goodness. Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.’

What is compelling about Waismann’s view is that is recaptures the philosophical spirit, it reminds us why we started. It reassures us in our hours of solitude, when we are trapped deep in a problem—a snare which we nonetheless find energising. It reassures us when, at our desks, in our libraries, we struggle to formulate our nascent insights into accepted parlance. It reassures us that we are on the right course, so long as we are asking the questions that stir us the most: ‘You don’t choose a puzzle, you are shocked into it’ (Waismann, 1968: 37). It rings in tune with our restless, roving minds.

‘The heart’s unrest is not to be stilled by logic.’

(Waismann, 1968: 13).

Descartes, René. 1997 [1637]. Von der Methode des richtigen Vernunftsgebrauchs und der wissenschaftlichen Forschung. Übs.: Lüder Gäbe. Felix Meiner: Hamburg.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. 1847. Essays: First Series. http://www.emersoncentral.com/essays1.htm.

Pienaar, Jacques L. 2016. The Relativity Principle in Quantum Mechanics. http://perimeterinstitute.ca/videos/relativity-principle-quantum-mechanics.

Spinoza, Baruch de. [1677]. Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata. („Ethik, nach geometrischer Methode dargestellt“).

Waismann, Friedrich. 1968. How I See Philosophy. Ed. R Harré. Macmillan: London.