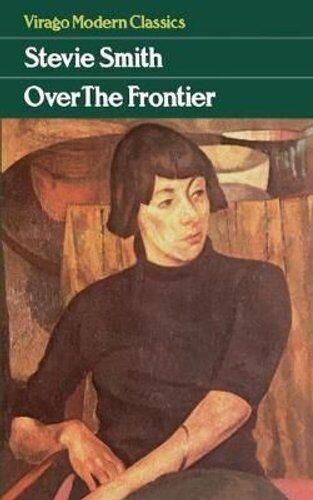

Book Review by George S: I have often enjoyed Stevie Smith’s poetry, but had never tried her fiction. This month at the Popular Fiction Reading Group we are investigating the first twenty-five titles on the Virago Modern Classics list, which offered an opportunity to find out more. I approached Over the Frontier with curiosity, and it turns out to be a very odd book indeed. Essentially, it is the stream of consciousness of a character called Pompey who is very like Stevie Smith – same job in publishing, same difficult relationship with a man, very similar aunt, same original and quirky mind.

The book is complex and allusive. It is the sequel to her first experiment in prose fiction, Novel on Yellow Paper (1936), and perhaps I might have found the first pages of this book less confusing if I had read that one – since this book cheerfully assumes that we know who Freddy (the unsatisfactory man) and various other characters are. Stevie Smith does not go in for explanations, much.

She also expects her reader to have a wide frame of reference – there are mini-essays on the art of George Grosz, or of Goya, or the difference between Spanish and Femish painters when they depict cruelty, that would mean little to those who did not know the painters. Quotations from poetry are scattered through the book, mostly uncredited. Some are by Pompey (or Stevie} but others are by Blake or various metaphysical poets. I did a fair bit of Googling to check who wrote what.

We are a popular fiction reading group, and popular fiction this isn’t. One way of reading it is as a critique of popular fiction. The book is full of what Pompey calls: ‘the thoughts that go helter-pelter through my mind’; these thoughts flit from topic to topic subversively, in a pattern very different from the way that conventional narrative prose creates an illusion of normality. A developing theme of the book is violence, increasingly impinging on everyday life in the 1930s, and Smith/Pompey imagines an ordinary book describing horrors:

It is all so carefully, so painstakingly described, to make you sick,since the writing is so dead awful, so like the magazine story that is like a good second class woman’s magazine story.

Over the Frontier is not like a good magazine story, of any class. Pompey has her own language, mocking normal discourse with nicknames and facetiousness and adding -o to any word she has become bored with. In the first half of the novel, the narrative interest is minimal, though the insights and reflections are often brilliant. Pompey’s mind keeps coming up with the unexpected; it’s less a stream of consciousness than a picturesquely undisciplined torrent of consciousness.

Pompey is deeply disturbed by cruelty, which she sees not only in human relations, and in German politics, but in the behavior of a cat towards the birds whom she has fed breadcrumbs and bacon rind:

Oh hateful cat with green deceitful eyes, coming up early in the morning from what ramshackle night of love. Away most unsympathetic of animals, away marauder.

The book can be read as response to conventional ways of writing about the subject:

There are some writers, I name no names, that make a lot of money writing about pain, pain is to them an inexhaustible fount of inspiration and a regular income.

Pompey, you might think, with her scatter-brain and her hatred of violence, is the least likely character in the world to become a secret agent – but that is what happens to her in the second half of the novel. She is taking a rest-cure in a German schloss sanatorium-hotel, and becomes increasingly involved with the calm authoritative Major Tom Satterthwaite, with whom she goes riding.

Mysterious things happen, and she is passively recruited. There is a remarkable scene where Major Tom hurriedly dresses her in a coat, and she is amazed to find that she is in uniform.

Oh Tom, only you should not have put me in this coat, yes Tom, indeed you should not. I do not like to be in uniform, to prance round and be a soldierly female, I have a sort of horror of that sort of female, that is always bouncing about and being so uniformly and so controllingly upstage and arbitrary, it does not sit well with the female, I do not like it.

What happens then is that her behavior changes to fit the uniform. She becomes a tireless messenger over the frontier – though what she is actually doing remains vague, as do the progress of the war, and the reasons for which it is being fought. She out-performs even the authoritative Tom,

I have succeeded where he has failed, and the messages that come to us are for me and not for him.

She achieves praise from the Archbishop (who seems to be the leader of their ill-defined cause).; she becomes fully a soldier, and kills her enemies:

For pride and revenge the blood flows out, and for a foolish ideology that I saw writ up so plainly to flicker upon the inspired wooden faces of the soldiers I had shot down.

She ponders ‘how frightful it was, and how amusing to be able to destroy’.

Pompey becomes aware of ‘the darkness of ferocity about me and within me’, and the book as a whole is a contemplation of how anybody – even Stevie Smith, could drift into an acceptance of brutality.

The introduction to the Virago edition suggests that the second half of the novel, with its obscure military actions in a vaguely defined war, could be read as the dream of the Pompey of the first half of the novel. But perhaps even that is to allow the book too much naturalism. I think it is a literary experiment, an improvisation discovering what happens to the Pompey way of thinking and behaving when it meets the conventions and assumptions of a John Buchan thriller, or the reality of thirties Europe.

As a literary experiment the book is fascinating; as a novel it is frustrating. And it’s definitely not popular fiction.

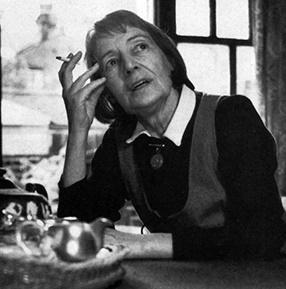

Stevie Smith (1902-1971)