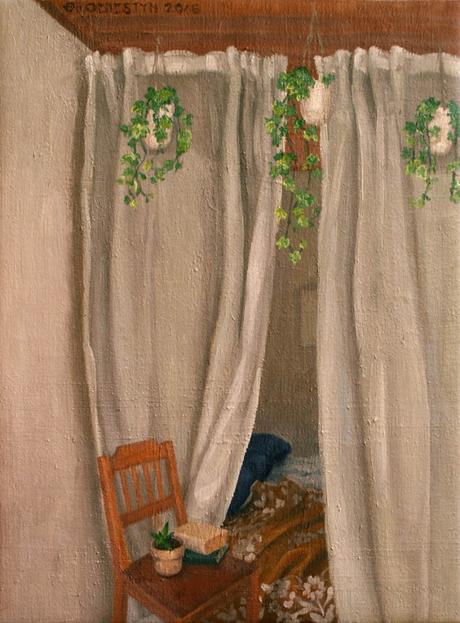

Das Bett / The bed (c) Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

Richard Wollheim’s meticulous and absorbing book Painting as an Art stands, all three hundred and fifty hefty pages of it, in opposition to explanations of meaning in painting that depend on comparisons with language. I have found some useful analogies for painting in language, but such a rigorous book leads me to consider that my preoccupation with an ill-defined ‘visual language’ disguises a deeper concern with meaning itself in painting. I have considered Susan Sontag’s (1969) argument that ‘silence’ in paintings belies an absence of meaning, and have picked up her appeals to a kind of discussion, a back and forth between painter and spectator. But perhaps it is more illuminating to be yet clearer about the type of meaning that is to be manipulated (by the artist) and found (by the spectator) in paintings, and to be strict about the distinction between painting and language.

Painting as an Art inextricably binds meaning in painting to the materials of painting. Paint itself can be transformed into a medium that can ‘be so manipulated as to give rise to meaning’ (Wollheim 1987: 7). What Wollheim (1987: 15) wants to hold on to here is the very ‘paintingness’ of a painting as integral to its meaning—that meaning must be contained within the painting, implanted in it by the artist, discoverable by the spectator, and independent of external validation or explanation.

‘Pictorial meaning,’ concedes Wollheim (1987: 22), ‘is diverse.’ From the outset, he casts aside any theory with a linguistic scent. ‘Structuralism, iconography, semiotics and various breeds of cultural relativism’ look for the kind of meaning that language has in painting. That is, they try to make sense of paintings by decoding them according to a variety of rules and conventions and symbol systems. But, argues Wollheim (1987: 22), while these sometimes influence the meaning of a painting, such codes do not lie at the heart of pictorial meaning.

And so Wollheim (1987: 22) sets out his own account of pictorial meaning, which he brands a psychological account in contradistinction to these linguistic theories. The core components of this account—and there are three—align happily with factors I have, as a painter myself, come to consider crucial in appreciating painting. Though initially uncomfortable with the term ‘psychological,’ I grow ever more convinced that it captures as fundamental something of the elusive inner, emotional machinations of the artist which a linguistic account might only add on later. Wollheim’s (1987: 22) triad of factors upon which pictorial meaning rests are:

-

The mental state of the artist

-

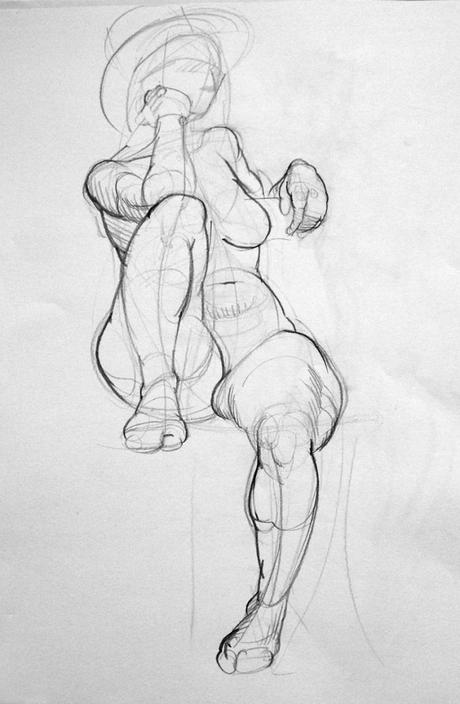

The way this causes him to mark the surface

-

The mental state that the marked surface sets up in the sensitive and informed spectator.

Or, more descriptively (Wollheim 1987: 22):

‘On such an account what a painting means rests upon the experience induced in an adequately sensitive, adequately informed, spectator by looking at the surface of the painting as the intentions of the artist led him to mark it. The marked surface must be the conduit along which the mental state of the artist makes itself felt within the mind of the spectator if the result is to be that the spectator grasps the meaning of the picture.’

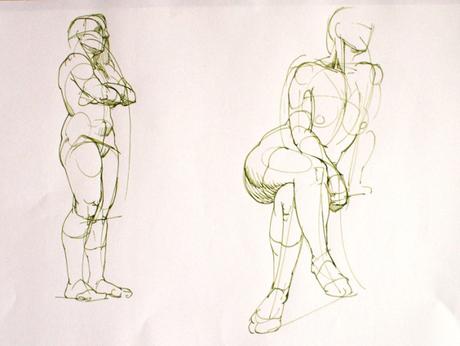

Beginning with the painter (for, as Wollheim (1987: 36) argues, ‘if we are interested in understanding either painting as such or individual paintings, we must start from the artist’) demands something substantial of the painter. It says that we expect her to embody some thought, some idea, in the paint she is carefully mixing on her palette, preparing to smear across her canvas. It does not say that we demand to know her history, her biography, her certified statement on the meaning of the painting. Wollheim (1987: 44) emphasises again and again that the information we seek should be embedded in the painting itself. Turning to the painter’s mental state is important because it demands an intention of her, not something careless, accidental, or mindless. A painting that does not embody a meaningful idea does not qualify, on Wollheim’s (1987: 13) terms, as art—and he is keen to do away with the type of painters that are not artists. This addresses Sontag’s (1969) concern for silent paintings that in fact have nothing to say to the spectator, without yet having to depend on a spectator. For the artist’s ‘major aim,’ so Wollheim (1987: 44) contends, is ‘to produce content or meaning.’

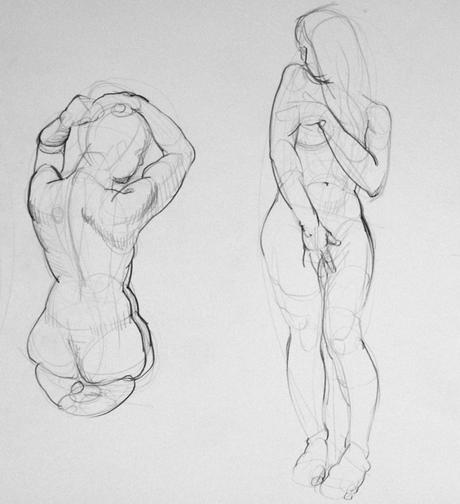

Wollheim (1987: 185) does not deny the spectator a role, but he treads very carefully where he fears that a painting might be endowed with meaning ‘after it left the hands of the artist and without any concomitant alteration to its marked surface.’ For this reason, he asks us to call to mind the posture of the artist: standing in front of her easel. This image of the artist before her work should continually remind us that the artist herself occupies ‘a multiplicity of roles:’ she must be both agent and spectator (Wollheim 1987: 43). ‘Inside each artist is a spectator upon whom the artist, the artist as agent, is dependent’ (Wollheim 1987: 43). This precise formulation captures exactly what I have observed when I have considered the self-indulgent hours an artist may pass considering her own work, without even picking up a brush: the apparent idleness that is actually a necessary (though passive) role by which the artist tests the calculated effect of her work (Wollheim 1987: 95).

We must, argues Wollheim (1987: 96) take care to recognize that the artist hypothetically, not categorically, imagines a spectator when she herself steps into the role of spectator. She does not necessarily paint with a specific spectator in mind, nor even approach her work with the attitude that another spectator will ever approach the painting. This further distinguishes painting from language, in Wollheim’s eyes. A painting may or may not be a form of communication, but it is not inherently a mode of communication. ‘Necessarily communication either is addressed to an identifiable audience … or is undertaken in the hope that an audience will materialise’ (1987: 96). I am not thoroughly persuaded on this point. A writer may similarly write for themselves, or for no one, in precisely the medium of language. Reams of private notes or sketches can be records addressed precisely to their creator in her role as spectator. The artist’s multiple roles seem, rather, to enable the possibility of an internal conversation.

It is through marking the surface, intentionally applying paint, that the artist attempts to give form to and perhaps eventually to convey her thoughts. Among the artist’s intentions, Wollheim (1987: 86) lists ‘thoughts, beliefs, memories, and, in particular, emotions and feelings, that the artist had and that specifically caused him to paint as he did.’ The key is that there ought always be a connection between the marks set down and the inner, mental state of the artist. For Wollheim, this connection is never one of direct transcription, as in language, but there is always a correspondence.

But more than this: the artist also intends that ‘a spectator should see something in [the marked surface]’ (Wollheim 1987: 101). This particular intention is what Wollheim calls respresentation. He (Wollheim 1987: 101) here finds room to introduce a standard of correctness and incorrectness: Since the artist had something in mind, and tried to put it down, a spectator might understand that intention correctly or incorrectly. Of course, spectators bring all sorts of personal musings to a painting, and there is a case to be made for reverie, but these wayward, subjective reflections can never comprise the core meaning of a painting. The artist’s intention can be grasped or misunderstood, or partially recognised. But respect for the artist’s intention is crucial if we are to salvage painting from the meaningless mire of subjectivity. Our personal reflections ought only augment the artist’s original idea.

The second important point here is that the spectator should discover this idea in the marked surface. We move smoothly from the intentions of the artist to the response of the spectator via the uncomplicated physicality of paint itself. We spot a glimmer of hope that ‘the sensuous and the meaningful can here for once be fused into an indissoluble unit,’ as Ernst Gombrich (1996: 453) writes of the Greek awakening to the expressiveness of the human form. The spectator can expect to discover, with enough patience and attention, what the artist hoped to convey, by viewing the picture itself. The painting reveals, after all, the way in which the artist worked. If we acknowledged this, rather than fumbling for written explanations of paintings, we would come a long way in restoring dignity to painting as a carrier of meaning.

The spectator, in turn, must bring something to the painting in order to grasp its meaning, though not in the sense of permitting a plurality of meanings, nor in the institution-dependent sense of being thoroughly educated in art history or appealing to authorities. The ‘sensitive’ and ‘informed’ spectator brings, rather, certain fundamental perceptual capacities, on Wollheim’s (1987: 45) account, and there are three:

-

Seeing-in

-

Expressive perception

-

The capacity to experience visual delight.

Wollheim is a delightfully thorough writer: he is strict on his terms and takes the time to develop each of them fully, probing their weak spots and plugging them with logically necessary qualifications. One must not be deterred by his terms: though precise, they are not as difficult as their rigidity makes them appear. I am so taken with his explanations of the above three capacities that I intend to devote far more attention to them in dedicated essays. For now, let us introduce them, keeping his broader system in view.

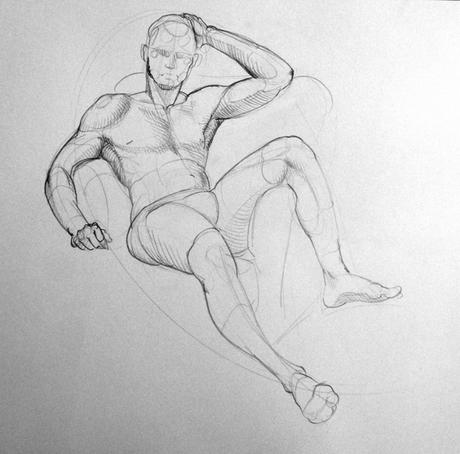

By seeing-in, or twofoldness, Wollheim (1987: 46) means the very remarkable yet familiar experience of being aware of a surface but at the same time seeing something in it. This is, I contend, one of the most important aspects of a painting: it is not merely an image, nor do we desire to be completely drawn into some illusion of reality. The physicality of paintings stands ever at the fore. The very paint is seductive and never quite escapes our view, whatever image we see. Wollheim (1987: 46; 71) calls seeing-in a ‘distinct kind of perception’ upon which representation depends. The spectator, then, should notice both the paint and what is represented in paint, and see that both play a role in the meaning of a painting.

Emotion, that slippery aspect that ever eludes language but seems to be the particular strength—and perhaps even point of—art, enters with expressive perception. We know from experience that we are able to look at a painting and see it as depicting an emotion, and it is simply this ‘species of seeing’ that Wollheim (1987: 80) wants to capture with this term. He (Wollheim 1987:80) believes that because it is a genuine species of seeing, ‘it is capable of grounding a distinctive variety of pictorial meaning.’ What is attractive about this account is that it tries to establish the emotional content of a painting as a credible part of the meaning of the painting. The spectator must be attentive to it, and able to follow the painter’s cues, which may be far more complex than symbols.

The artist relies on the sensitive and informed spectator to bring a certain ‘cognitive stock’ to the painting in order to uncover its meaning, particularly some information about how it came to be made. But, Wollheim (1987: 89) emphasises, this information should be embedded by the artist in the painting itself. ‘What is invariably irrelevant,’ he (Wollheim 1987: 95) writes, ‘is some rule or convention that takes us from what is perceptible to some hidden meaning: in the way in which, say, a rule of language would.’ This information only gives itself up slowly, with long and attentive deliberation, and perhaps a familiarity with the larger body of the artist’s work. ‘Often careful, sensitive, and generally informed, scrutiny of the painting will extract from it the very information that is needed to understand it’ (Wollheim 1987: 89).

Lastly, the artist demands of the spectator the ability to experience pleasure in his encounter with art. Pleasure does not simply come from subject matter, Wollheim (1987: 98-99) argues, but rather from the way the artist carefully controls the spectator’s propensity to see the emotional character she has laid over an otherwise recognisable, and perhaps utterly ordinary image. Without the capacity for visual delight—which the artist is bursting to transmit—the spectator would remain unmoved by painting; an impenetrable barrier would ever stand between him and the appreciation of paintings, their meaning would ever elude him.

Wollheim’s Painting as an Art is dense but rewarding: his search for meaning within the painting itself, driven by the intention of an artist with something to express, not only restores dignity to the distinctly visual nature of painting, but does so without recourse to language or its associated symbols, conventions and syntaxes, which he considers an unfortunate and ‘ill-considered analogy’ (Wollheim 1987: 181). Ever reminding us of the limitations of such an analogy, Wollheim offers instead a persuasively thorough conception of meaning in painting that I find well worth deeper consideration. This continual return to the painting itself is just the sort of philosophical system that seems to allow for a breed of objectivity to surface. And this is a path through the murky forest of aesthetics which I should like to go down.

Gombrich, E. H., and Richard Woodfield. 1996. The Essential Gombrich: Selected Writings on Art and Culture. London: Phaidon Press.

Sontag, Susan. 1969. ‘The aesthetics of silence.’ In Styles of radical will.

Wollheim, Richard. 1987. Painting as an Art. 1. publ. London: Thames and Hudson.