The Rokeby Venus (1648-51), by Velázquez

The Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, has put on a remarkable Velázquez show that has afforded me a much deeper understanding of this Spanish heavyweight. I know that painters are supposed to adore him by default, but despite the Queensland Art Gallery’s efforts a few years ago, I have come quite late to this party. I stand by the view that it’s best to keep quiet about things you don’t understand, and to take as long as you need to come to terms with something on your own. You don’t have to fake it!

Natürlich, the former imperial seat of Vienna has much cultural clout and is presumably more trustworthy around nice things than that convict island somewhere well across the seas, such that the Prado, Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie and London’s National Gallery among many others across the world have graciously loaned some seriously significant works to our fair city and her already impressive stock of Velázquezes, making for an achingly spectacular exhibition.

Gloriette, Wien

One might lament that a roughly chronological exhibition is somewhat unimaginative, but the progression rather wonderfully traces Velázquez’s artistic growth. Each dimmed and solemn room is a cluster of works from distinctive times and places in the painter’s life, a fact that is obvious without needing reference to a guide book or captions. The first room is respectfully darkened, its rich wine-red walls closing in on you, that woody, furniture-polish scent of the Kunsthistorisches filling the air like incense. A serious reverence hushes this room, which is hung with saints and peasants: Velázquez’s earliest works from his native Seville. These paintings feel as if they emerged from the hot earth itself: warm and deep oranges and browns, as earthy as one imagines Spain to be. The saints sit steadfastly in their voluminous, course robes, complex godly thoughts straining their faces, their gnarled hands like roots from the ground, painted with love and precision. Sweet and lavishly-coloured egg-shaped Marys look down graciously from turbulent clouds, stars lacing their heads, and their hands gracefully prayerful. The painterly precision of these paintings is delicious.

The three musicians (1617-18), by Velázquez

But the most heart-warming picture is the Three musicians (1617-18), who normally live in Berlin, painted when Velázquez was only eighteen years old. One hears Velázquez bursting, like his compatriot Dalí many centuries later, ‘Hurry up and grow old—you are horribly “green,” horribly “bitter.” How, before I reached maturity, could I rid myself of that dreamy and puerile infirmity of adolescence?’ This painting has the colouring of his other Seville paintings, and even the same sort of characters. His understanding of light and shade is solid, and his composition is far more daring than a youthful still life, with extremely satisfying design elements like the sure sweep through the boy’s downturned hand. The perspective through the instruments is endearingly skewed, but otherwise it is difficult to fault his execution. Yet Velázquez is not yet himself, and in but a few short years, at the nearby Waterseller of Seville (1622), we are treated to such an advancement in modelling, in tonal and pictorial hierarchy, in the treatment of texture, and in the pronounced fullness of forms, that we must be aware that we are in the presence of greatness. And this is only the beginning. For the lesson of Velázquez is that one can always learn, and always advance, and each mastery of a skill attained only opens the door to more powerful abilities to be learned. But the importance of chronology to this exhibition (at least to the painter student) is this: one cannot start at the end, with the effortless and airy brushstrokes of the Rokeby Venus (1648-51). This is an advanced level of fluency with paint, not a careless ‘style’. And we can appreciate this when we see Velázquez’s humble and determined origins, wrestling with the muddy pigments of Seville.

The Waterseller of Seville (1622), by Velázquez

You leave this room through an antechamber with one painting to each side and one before you. These pictures mark an important transition for Velázquez, as the one to your right, a portrait of the distinguished and well-connected Don Luis de Góngora (1622), brought him enough acclaim at the budding age of twenty-four to have him invited to paint a portrait of the King. The humble and elegant Portrait of King Philip IV (1623-4) lies to your left: cropped below the shoulders, as is the Don, and strikingly lit richly coloured flesh is set against caramel backgrounds. Their faces are deliberately planar and hard-edged, everything carefully placed where it ought to be, as though a mark of respect. The king’s hair is one delightful smooth-gelled mass, its rippling but singular volume indicating Velázquez’s sculptural way of conceiving of feathery masses—an early insight into his later facility with wafting hair and explosive lace. In his mind, one suspects, he always saw such indistinct surfaces as full and voluminous forms, whatever his increasingly competent brushwork deceives us into thinking.

Portrait of King Philip IV (1623-4), by Velázquez

King Philip IV was also duly pleased with his Elvis quiff, for he promptly hired Velázquez as court painter and refused to be painted by anyone else. On our way to the dramatic and high-ceilinged Baroque hall of court paintings, we are treated to some luscious larger portraits which begin to exude a confident and expert softness of paint, as though they melted right off the brush. Portrait of a lady (1630-33), pinched from Berlin, and Portrait of Juan Mateus (1632) are stunningly mature works. Juan Mateus’s sharp, black irises peer out of a roughened face. Every lump and pucker is attended to, the heavy bags under his eyes, but with a new delicacy of edge. A haze up close, the features are true and distinct from afar, because Velázquez’s softer mode of painting is not a shortcut or a cover up of a lack of knowledge. Rather, his earlier deliberate work has, over many years, formed a solid foundation for freer movement. His hands begin to catch up with the fleeting impressions that kiss his eyes because he knows what structures lie beneath them. These pictures still carry the warm earthy tones of his saint pictures, the lively flesh set against honeyed caramels, and an elegance of design despite the focus on the faces. There is much use of the space around the figures, and the large and bulging egg-shapes of the bodies are accentuated with arm gestures and clothing embellishments—a happy union of form and design. The woman’s sumptuous dress is faithfully embroidered, her pearls individually rendered, but all lavishness is tastefully subordinated to the greater picture.

Portrait of a lady (1630-33), by Velázquez

Vienna has surpassed herself: we enter the grand hall decked with court paintings and realise that this entire exhibition serves to showcase her already impressive collection of Velázquez paintings, accumulated through years of intermarriage between Austrian and Spanish royalty. Better than a postcard: receive a yearly larger-than-life painting of your betrothed throughout her childhood and see how that rosebud is blossoming. The absurdity and glamour of court life takes a firm hold of Velázquez and we see him transform yet further: The tiny Margaritas sparkle in their shimmering dresses; the pearlescent and grotesque inbred faces of sickly royalty give him new forms, new shapes and new textures to adapt his well-trained skills to. Parachute skirts and elaborately piled hair fare well under his sense for design. Now Velázquez is such a sure painter that he implies as much as he describes. The complex pattern of Queen Mariana’s light red dress (1651-61) is reduced to a brisker grey and red contrast of shapes that offset to produce a shimmering pink and silver. And, of course, Vienna’s starlet, The Infanta Margarita Teresa in a blue dress (1659), famously shimmers at a distance, though up close her dress seems but a careless spattering of blues, of dull grey and neutral yellow. The liveliness of this painting and the sureness of touch become quite clear when it is hung next to a copy, as it cleverly is here. Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo’s green dress variation (1659) fails to translate the illusion-generating contrasts into green and gold. Worse, his fast and loose brushstrokes don’t hang from a knowledgeable scaffolding: mashing on some white fuzz where lace ruffles ought to be does not begin to approach Velázquez’s light touch that actually indicates a full structure.

The Infanta Margarita Teresa in a blue dress (1659), by Velázquez

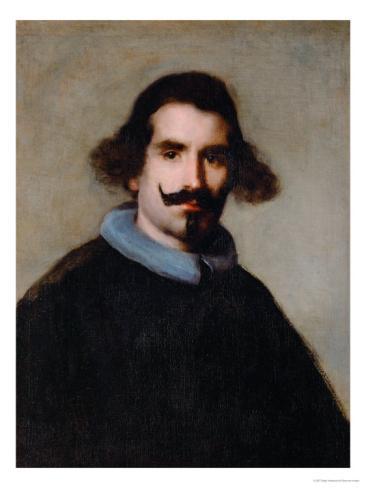

More corridors bring us to the finale, a room packed with deftly-executed works, many as humble as the earliest, though bursting with the vigour of experience. Velázquez is not consumed by the grand regal images, but brings his evolved powers afresh to small, dignified portraits and allegorical pictures. Several dashing moustachioed Spaniards, their pencil-thin moustaches all pointing towards heaven and no doubt goading Dalí to painterly greatness, use all of his accumulated knowledge in a stripped-back, elegant manner. Portrait of a man (self portrait?) (c. 1630) boasts a daringly rough edge sweeping down the side of the thinly painted black coat. The audacity of this gorgeous mark is enough to make a painter tingle. The nebulous cloud of hair floats thick but weightless about Velázquez’s brow, and a subtle twinkle plays in his quietly thoughtful eyes.

Portrait of a man (self portrait?) (c. 1630), by Velázquez

A small, near-square Female figure (Sibyl with Tabula Rasa) (1648) is equally limited in colour, and the sibyl is draped in simple cloth, but this picture is wonderfully composed. Her gorgeous profile is in shadow, but her rosy cheeks glow fiercely; the background quietly supports her, making a dramatic but somehow unobtrusive change from dark—behind her light hair—to light—behind her shadowy face. The sibyl herself is full and round like a Rubens figure, and the arcs through her body and clothing and arms enclose her in a deliberate though unselfconscious design.

Copy after Velázquez, female figure (Sibyl with Tabula Rasa)

And, unless you began the show at the end (as did I, breathlessly storming the marble staircase of the Kunsthistorisches after too many months away), you will at last come face to face with the infamous Rokeby Venus (1648-51), who stares blithely back at you through a dimmed mirror right above her achingly lovely behind, which you had hoped to appreciate unnoticed. I’ve heard her lauded as ‘the finest nude;’ Kenneth Clark (1985: 141) registers her importance by including her as the first picture in his comprehensive book on The nude, though only describes her as ‘dispassionate.’ And what shall I say of her? That the silks and satins, breathily painted, must be intentionally course to dazzle us by how perfectly fleshy that pale and luminous figure is? That Velázquez is a master of subtlety? The quietness of the pink, blue and white is in remarkable contrast to the sizzling red-oranges of Seville and the fanfare of colour of the court. This painting is a mystery to me, a surprising anomaly in Velázquez’s oeuvre. Perhaps its brilliance lies in his ability to bring a lifetime of learning to this age-old subject and treat it with fresh delicacy and empathy. For Velázquez could not even paint a nude without regard for her thoughts, reflected back at us in her defiant face, just as his brush illuminated peasants, saints, kings and princesses and dwarves with equal dignity.

Rokeby Venus (1648-51), by Velázquez

And so, in mastering our craft, we mustn’t get ahead of ourselves and try to start at the end. For our humble beginnings are cementing the foundation for our careers, for our entire lives. And whether we paint peasants or royalty, clay pots or pearls, our brush should focus with devotion on the excitement of the visual, on the possibilities of paint. The painter makes no moral judgements, but casts her levelling eye over all humanity and finds its dignity through the language she knows: the language of shapes and forms and colours. And in the end, it is all made of earth.

Clark, Kenneth. 1985 [1956]. The nude: A study of ideal art. Penguin: London.