Zebra finch genetics

The zebra finch, Taeniopygia guttata, is an Australian songbird with a black and white striped breast, used by neuroscientists as a model organism to study the learning and production of a complex motor behavior–birdsong. Like other songbirds[1], zebra finches are genetically predisposed to learn their species’ particular song, but they have to hear the song being produced and slowly learn to mimic it through a trial and error process, similar to how babies learn to speak.

Zebra finches

So out of the over 5,000 identified passerine songbirds, why did neuroscience choose the zebra finch as its model songbird? For similar reasons, to why biology chose the mouse as a model mammal–zebra finches are small, easy to care for, and breed well in captivity. However, with any lab-bred animals there is a risk of inbreeding, which could alter the results of studies and effectively create subspecies reducing comparability between labs.

Lab bred animals – inbred strains of mice

To reduce genetic variability within studies and increase comparability between labs, mouse geneticists have intentionally mated strains of mice to be inbred. By breeding mice with their siblings for ten generations[2], they generated animals homozygous at essentially every allele. In other words, all of the animals born from this process have the same genome[3], with the same copies of each gene on each chromosome. These animals are essentially genetic clones of one another, and if they reproduce with each other their young will clones as well. Through this process we created standardized inbred strains of mice such as C57/BL6Js or BALB/CByJs that are used in labs around the world and maintained by organizations such as The Jackson Laboratory.

Inbred strains have been essential for research, however they can sometimes produce idiosyncratic results, that don’t generalize to other strains, let alone mammals in general. For example, knocking out a gene in one strain may have an obvious phenotype that is conspicuously absent in another, likely because other genes can compensate in the second strain. In extreme cases, inbreeding can fundamentally alter normal characteristics of the species and predispose pathological states, for example BALB/cWah1, are predisposed to lack a corpus callosum. About 20% of mice have no CC and another 20 to 30% have an unusually small CC. Scientists have therefore argued that while data generated from inbred strains might be more reproducible, it may also be less generalizable. You have reduced experimental noise and you can reproduce the same results, but are they robust findings that generalize to all mice or only a particular strain.

Are zebra finches inbred?

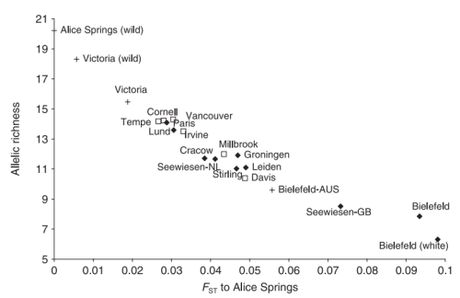

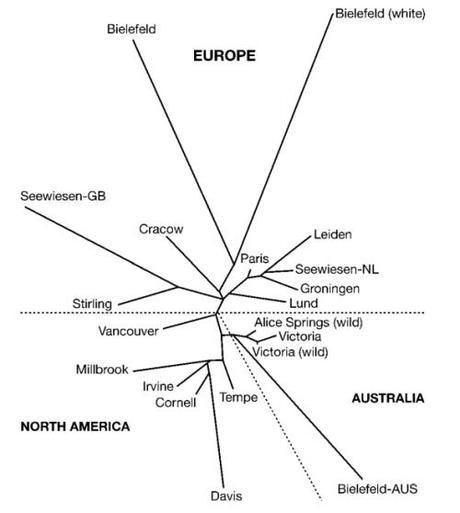

There have been no efforts (to my knowledge) to generate an inbred laboratory strain of zebra finches. However, there could potentially have been bottlenecks during the process of domestication and shipping birds between continents that have reduced genetic diversity within laboratory populations of the species. To investigate the population genetics of laboratory zebra finches, researchers genotyped 1000 zebra finches from 18 laboratory populations (held in Europe, North America, and Australia), and two wild populations at 10 microsatellites. Microsatellites, are sequences of repeats of 2-5 base pairs that tend to be quite polymorphic, making them good markers for genetic diversity[4].

Forstmeier 2007

As might be expected, laboratory populations showed loss of genetic variability, due to genetic drift. If in a population a particular allele every drifts to zero, then it is lost in that population. Lab populations on average had roughly half the number of alleles per locus compared to wild zebra finches—11.7 for captive versus 19.3 for wild. The most inbred population studied, a population bred for the recessive trait of white plumage showed only 6.4 alleles per locus, roughly a third of the alleles per locus seen in the wild populations. Researchers found genetic differences between zebra finches found in their European and North American populations and pointed out that there could be functional differences between these populations as well.

Forstmeier 2007

The study looked at some functional differences between populations of zebra finches. Populations varied greatly in body mass, with some laboratory populations weighing almost double that of newly domesticated populations (and although body mass may be affected by animal husbandry and housing, this result was true even for three genetic separate populations housed in the same lab). Body weight of animals can be important for scientists who may wish to place electrodes, cannuli, or other devices on birds heads, but it was mainly used as an easy and reliable measure to show real differences between the populations. It is possible there are differences to brain structures and genes involved in learning and plasticity that may affect song structure as well. Such differences are more difficult to demonstrate, but also important to know as they could affect and possibly complicate results from studies.

In sum, the laboratory populations studied zebra finches are somewhat inbred, but still show diversity. If studies conflict between North American and European laboratories, we should consider if genetic effects might explain the differences. Perhaps we should begin inbreeding strains of zebra finches to facilitate genetic studies in the future. Also, we may need to investigate other lab bred species of songbirds used by researchers such as Bengalese Finches, which have been bred in captivity for centuries and selectively bred for their plumage.

————————–

[1] (Parrots and hummingbirds are also vocal learners.)

[2] This process of sibling-sibling breeding is also known as “selfing.” The Ancient Egyptians, believing the royal family to be gods bred brothers and sisters for 10 generations, and likely created humans homozygous at each allele.

[3] Of course, due to the sex chromosomes, males and females will have different genomes, and a small number of new mutations occur with each generation.

[4] Though they are far from perfect: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microsatellite#Limitations. Although mutations can complicate analyses, previous studies by Forstmeier et al. demonstrated that they are extremely rare in Zebra finches — they did not observe a single event in their microsatelli loci in 7368 parent offspring comparisons.

References:

Forstmeier W, Segelbacher G, Mueller JC, Kempenaers B. Genetic variation and differentiation in captive and wild zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Mol Ecol. 2007 Oct;16(19):4039-50.