It’s human nature to abhor admitting an error, and I’d wager that it’s even harder for the average person (psycho- and sociopaths perhaps excepted) to admit being a bastard responsible for the demise of someone, or something else. Examples abound. Think of much of society’s unwillingness to accept responsibility for global climate disruption (how could my trips to work and occasional holiday flight be killing people on the other side of the planet?). Or, how about fishers refusing to believe that they could be responsible for reductions in fish stocks? After all, killing fish couldn’t possibly …er, kill fish? Another one is that bastion of reverse racism maintaining that ancient or traditionally living peoples (‘noble savages’) could never have wiped out other species.

It’s human nature to abhor admitting an error, and I’d wager that it’s even harder for the average person (psycho- and sociopaths perhaps excepted) to admit being a bastard responsible for the demise of someone, or something else. Examples abound. Think of much of society’s unwillingness to accept responsibility for global climate disruption (how could my trips to work and occasional holiday flight be killing people on the other side of the planet?). Or, how about fishers refusing to believe that they could be responsible for reductions in fish stocks? After all, killing fish couldn’t possibly …er, kill fish? Another one is that bastion of reverse racism maintaining that ancient or traditionally living peoples (‘noble savages’) could never have wiped out other species.

If you’re a rational person driven by evidence rather than hearsay, vested interest or faith, then the above examples probably sound ridiculous. But rest assured, millions of people adhere to these points of view because of the phenomenon mentioned in the first sentence above. With this background then, I introduce a paper that’s almost available online (i.e., we have the DOI, but the online version is yet to appear). Produced by our extremely clever post-doc, Tom Prowse, the paper is entitled: No need for disease: testing extinction hypotheses for the thylacine using multispecies metamodels, and will soon appear in Journal of Animal Ecology.

Of course, I am biased being a co-author, but I think this paper really demonstrates the amazing power of retrospective multi-species systems modelling to provide insight into phenomena that are impossible to test empirically – i.e., questions of prehistoric (and in some cases, even data-poor historic) ecological change. The megafauna die-off controversy is one we’ve covered before here on ConservationBytes.com, and this is a related issue with respect to a charismatic extinction in Australia’s recent history – the loss of the Tasmanian thylacine (‘tiger’, ‘wolf’ or whatever inappropriate eutherian epithet one unfortunately chooses to apply).

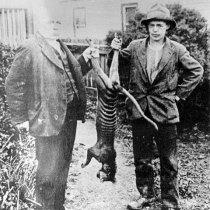

For those of you who don’t know, the thylacine was a beautiful, wolf-like marsupial predator that once roamed the entirety of the Australian continent. However, by the time Europeans arrived, it was restricted to the island of Tasmania (more on the reasons for that in an upcoming paper also by Tom Prowse, which I’ll cover in another post later). Unfortunately as is typical of livestock farmers in Australia (and elsewhere), predator xenophobia took hold because people were convinced that thylacines were eating too many of their sheep. So, in a colossally misinformed (and typical) manner, the government instituted a bounty to cull the thylacine population in a bid to reduce sheep predation. The last known thylacine died in a zoo in the early 1930s.

Enter the anecdotal and entirely unsupported hypothesis that the only plausible explanation was that an unknown epidemic had occurred in the latter years of the thylacine’s demise. Combined with Bulte’s model and these anecdotes, the disease hypothesis took on a life of its own, to the point where it became the default explanation among ecologists and the general public.

Sound a little too simplistic? We thought so too. What about the massive land transformation that occurred after European farmers set up their trade? What about the major alteration of the prey base as macropods had to compete increasingly with the invading sheep? Somehow these important components were left off the thylacine extinction’s agenda.

Enter Tom Prowse and his population viability analysis (PVA) wizardry. Using a series of connected multi-species population models including vegetation changes, altered herbivore abundance, predator-prey responses, the bounty and a putative disease, we show clearly that there is absolutely no need to invoke a mystery disease to explain the thylacine’s extinction. Simple over-exploitation combined with prey modification is more than enough to account for the event.

Now – I won’t bore you holiday-recovering readers with the modelling details here. You can easily comb through the methods and assumptions we made in the paper once it goes online (I’ll make sure people know when it’s ready). And before you ask the obvious – that models cannot give the definitive answer – let me say that to date there is still no acceptable or evidence-based study that has done a better job to test the various hypotheses with the available data. Until we dig up an actual disease, the state of the art suggests that humans, and humans alone, were responsible for the permanent loss of one of Australia’s most interesting native species.

CJA Bradshaw

-34.917731 138.603034