NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) may have discovered its first free-floating or "orphaned" planet. That's a planet wandering through the cosmos, without a star, all alone.

The potential discovery shows that TESS can use a phenomenon first suggested by Albert Einstein more than 100 years ago to detect these so-called rogue planets.

Despite the fact that we are most familiar with planets orbiting a parent star (or stars) having discovered more than 5,000 exoplanets that occur in such an arrangement, the Milky Way is estimated to be populated with a large number of free-floating rogue planets. , at.

In fact, our Milky Way may contain as many as a quadrillion (10 followed by 14 zeros) rogue planets that have been expelled from their home systems by gravitational interactions with other planets or passing stars. That means these free-floating worlds could be much larger than the number of stars in the Milky Way. So the potential detection of such a cosmic orphan by TESS, which was launched in 2018, is a big deal.

Related: The mystery of how strange cosmic objects called 'JuMBOs' went rogue

"We discovered the first signal in TESS data that is consistent with what you would expect from microlensing by a free-floating planet," team leader Michelle Kunimoto, a postdoctoral researcher specializing in exoplanet detection at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), told Space.com.

"This was only the first sector we searched of the 75 that TESS has observed, with each sector corresponding to approximately 27 days of TESS observations," Kunimoto continued. "It was surprising to find something so early, but really exciting."

If this signal actually points to a rogue exoplanet, the team tells Space.com, it would likely be a planet with a mass several times that of Earth, at a distance of as much as 6,500 light-years deleted.

A little 'rogue hunting' help from Einstein

The majority of exoplanets discovered to date are referenced due to the effect they have on their host star. This could be a "wobble" in the star's motion caused by the small gravitational pull of an orbiting planet, or a dip in light that occurs when an orbiting planet crosses the surface crosses or "transits" from its star.

However, without a parent star, these methods are not applicable. That's what makes detecting rogue planets so difficult.

"Rogue planets are dark, as you would expect, and they don't orbit stars, which means the usual techniques for detecting exoplanets don't really work," Kunimoto said.

Fortunately, Einstein's 1915 theory of gravity, better known as general relativity, predicts a phenomenon that can be used to discover these free-floating exoplanets.

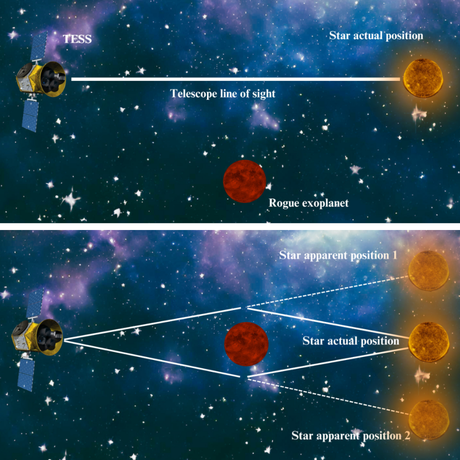

Einstein suggests that objects with mass curve the fabric of space and time, or spacetime, with gravity arising from this curvature. When light passes through one of those curved spots in spacetime, its path is curved. This means that light from a background source, such as a star or galaxy, can follow different paths around the intervening 'lens object', ending up in an observer's view at different times.

This phenomenon is called 'gravitational lensing' and results in the position of the background source shifting from the observer's perspective or appearing in multiple places in the same image.

Rogue planets have very little mass, so the lensing effect is weak and is therefore called 'microlensing'. Still, it can brighten a background source visible to astronomers, indicating the presence of a rogue planet.

"Microlensing is the best - and usually only - option for finding these dark, isolated objects, because it relies solely on a planet's mass through its gravitational field," Kunimoto said.

Forget the "T" in TESS

As the 'T' for transit in TESS suggests, this space telescope may not immediately seem like the right tool to hunt for rogue planets.

"TESS is designed to search for planets that are closely associated with their host stars by searching for transits," Kunimoto explains. "Transits are the dimmings of the star caused by a planet passing in front of it, as you may have seen in the recent solar eclipse."

However, as mentioned above, gravitational lensing can also cause a background star to brighten when a lensing object moves between that star and Earth. Kunimoto explained that because TESS is sensitive to small changes in a star's light, it can also detect these brightening episodes, a hallmark of microlensing caused by free-floating planetary rogues.

But given this fact, you might be wondering: why is this the first potential rogue exoplanet among the approximately 6,000 other exoplanet candidates (of which about 400 have been confirmed) that TESS has spotted since 2018?

Well, it turns out that no one was really looking until now.

"TESS is surprisingly well suited for finding rogue planets through microlensing, but it turns out that these types of signals have not been explored in TESS data before," Kunimoto said. "Our approach to searching for unbound planets using microlensing and the resulting planetary microlensing candidate from TESS were both firsts for TESS.

"Since TESS data had not previously been used to look for short-lived microlensing events, previous searches for exoplanets would not have been sensitive to seeing these signals."

Unfortunately, like many other detected exoplanet candidates, this discovery has yet to be confirmed.

"It's important to say that at this time we cannot confirm that this is a planet," Kunimoto said. 'The fact that microlensing events do not repeat means that it is difficult to distinguish the nature of a particular signal. So we are cautious about the origin of this event and call it a 'candidate' from a rogue planet because it is consistent with the signal you call 'candidate'. That's what I would expect from such a world."

She added that as the team examines more TESS data and conducts follow-up observations, the truth about the signal will slowly become clearer.

Still, the preliminary nature of these findings has certainly not diminished the team's enthusiasm or enthusiasm.

"Definitely a ten out of ten excitement from me," William DeRocco, team co-leader and researcher at the University of California Santa Cruz, told Space.com. "I'm used to looking for dark matter, where the chances of actually seeing anything are extremely slim, so the potential to discover something like a rogue world floating in the darkness of interstellar space is just incredible."

RELATED STORIES:

- A 'captured' alien planet may be hiding at the edge of our solar system - and it's not 'Planet

- There could be 400 rogue planets the size of Earth wandering through the Milky Way

- A cosmic 'fossil record' could be hidden among orphaned stars

The authors of this study believe that the future is bright when it comes to the prospect of TESS discovering even more rogue planets.

"This is a proof of principle that TESS can find these types of signals, and now it's up to us to dive deep into finding more and understanding what they could mean," Kunimoto concluded. "We've searched less than 1% of the signals. TESS data; with 99% to go, we have a wealth of new opportunities for exciting discoveries along the way!

The team's research has been submitted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. It is currently presented as a pre-peer review paper on the repository site arXiv.