Humans are undoubtedly the smartest animal on the planet, despite some people trying their best to show otherwise. Science has identified many aspects of our biology that contribute to our exceptional intelligence, such as our giant brains. Our brain is 4 times larger than that of our closest living relatives, the chimps, making it 7 times larger than it should be for an animal of our body size (Marion, 1998). As such, a lot of time and effort has been invested in explaining just why we evolved such large brains.

However, even though we’re discovering just what about us makes us so smart, it’s clear there is a lot left to figure out. Whilst we may have huge brains, there also appears to be something unique about the brain cells themselves. For example, humans possess a mutation which makes the connections between neurons denser, allowing more neurons to communicate.

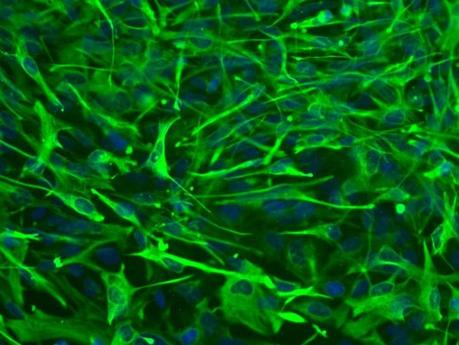

Now new research has identified yet another aspect of the human brain that contributes to our intelligence: the astrocytes. These are brain cells which aren’t directly involved in the transmission of information, like neurons. Rather, they help grow, nourish and repair the neurons. Human astrocytes are unusually large and complex, leading many to suspect that they did play a role in making us so intelligence.

Human astrocytes in the spinal cord (note they’re that color because of dye. Our spines aren’t actually bright green)

To test this hypothesis scientists collected a lot of human astrocytes from aborted foetal stem cells and injected them into some laboratory mice. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this generated a lot of controversy. Not only were they using foetal stem cells – a controversial move at the best of time – but they were using them to to create human/animal chimeras. The phrases “playing God” or “Frankenstein” are never far away from studies of this nature.

These mice were especially bred to have a deficient immune system so they wouldn’t reject the donated cells. The human cells survived and reproduced inside the mice, retaining their large size and complexity. Surprisingly, the human astrocytes worked with the mouse ones to perform their required tasks, like moving molecules around to provide nourishment for neurons. The two cell lines, despite being from completely different species were perfectly compatible.

After the researchers were satisfied the human astrocytes were flourishing enough that they should be having an effect on mouse intelligence they then gave the mice a series of tests. These ranged from memory studies to tests of their ability to learn. Mice injected with human astrocytes performed better on all of them, showing that astrocytes do indeed influence intelligence. Thus human astrocytes can help explain why we (and mice injected with them) are so smart.

But just what about the mouse brains had changed as a result of their infusion with human cells? It turns out that their neurons were communicating more frequently because the synaptic connections between them had been enhanced. Astrocytes play a key role in the growth of synapses, so it’s not too hard to see just what effect they were having on mouse brains and thus what role they might play in making humans so smart (Han et al., 2013).

So it would seem that astrocytes also contribute to our intelligence; and the intelligence of any mice they’re transplanted into. Despite the ethical qualms surrounding this research, I don’t think we’re at risk of being taken over by super-smart mousy overlords. No, the real source of concern should be the transdimensional mice using the earth as a giant computer.

References

Han X, Chen M, Wang F, Windrem M, et al. 2013. Forebrain engraftment by human glial progenitor cells enhances synaptic plasticity and learning in adult mice. Cell Stem Cell 12: 342–53.

Marino, L. 1998. A comparison of encephalization between odontocete cetaceans and anthropoid primates. Brain, Behavior, and Evolution, 51: 230-238.