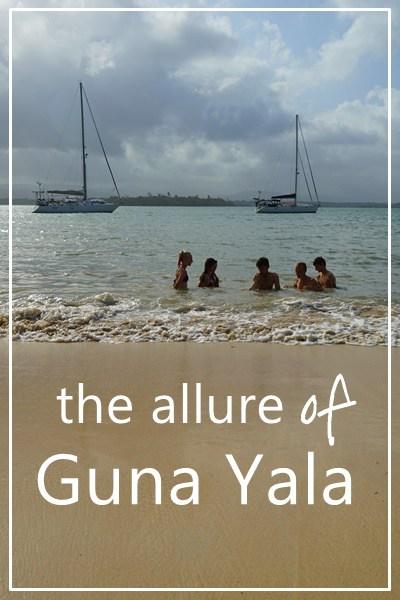

Headwinds. Choppy seas. Eyeball navigation through reefs where the usual tropical cues are absent. Days of gray skies. Taciturn communities. Few supplies. All features of our weeks sailing through the islands of Guna Yala (also known as Kuna Yala, or San Blas). Am I selling it yet? The

The territory includes around 350 islands along a coast of just over 100 straight-line miles. Communities pack into islands where homes constructed of cane and thatch butt up against one another, and footpaths are small enough in some cases to reach out and touch the low-slung palm roofline on either side. These alternate with islands which are largely uninhabited.

It is relatively disconnected: just a single four-wheel-drive road links the far western end to the rest of Panama. The only other “roads” are rivers and footpaths reaching into the tangled green jungle on the mainland: coastal waters are the real highway. Guna ply their dugouts by sail and outboard between islands; what isn’t grown or foraged is largely brought by Colombian supply boats.

Guna Yala is part of Panama… and it isn’t. Indigenous Guna people fought (and won) the right to self-determination and have largely rejected modern “civilization” in favor of preserving their traditions. Retaining this culture is not an outcome of their location, but a deliberate choice: although Guna Yala feels remote, the modern hub of Panama City with its millions of people and bright lights and shiny tech is within reach.

Google’s satellite view shows the density of a populated Guna island

Most islands have little more than coconut palms

Escaping the breaking swells in the clearance port, Obaldia, we shook off the difficult passage from Colombia in the placid water off Anachucuna village. Within a few hours with a shy young couple paddling their dugout to Totem introduced the first ritual of a Guna anchorage: anchoring fees. Uncommon in most of our travels, it’s the norm in the eastern San Blas. There; you’re expected pay whoever presents an officially stamped receipt on behalf of the local ‘congreso,’ the governing authority, and receive rights for a month in return. Too bad we were only staying overnight! I explained this to the visitor, asked for grace on the charge based on our short stay, and offered a handful of instant coffee packets as goodwill. A more social visit came from a father and son the following morning: in addition to their fishing handline, the bottom of their dugout included bananas, limes, and handicrafts to sell. Joining us in the cockpit we learned Andreas also had time, and was interested in talking. Or trying to, as our Spanish is weak and Guna language (Dulegaya) skills nonexistent! My first lesson in ensued, along with my first mola purchase.

Tucked in his basket were a few molas, panels of reverse appliqué panels used in women’s blouses. If you’ve heard about San Blas, you’ve probably heard about molas: the textiles are famous, for their intricate hand-sewn detail and vibrant illustrations representing everyday life or cultural motifs. The first mola he showed us was so nearly approximate a likeness to Totem’s orca, I couldn’t resist. Little did I know this was the beginning of what I now understand to be emola virus: by the time we sailed out of Guna Yala, the single panel had grown to a small stack in the aft cabin.

Totem moved steadily west, gunkholing from one island to the next with a night or two in each stop. It was a fast pace, but we hoped to secure an earlier canal transit (it didn’t work, oh well). Now is the dry season, but ironically, that’s when a cloudy haze obscures the mainland. Occasional breaks offer a tantalizing hint at rugged topography beyond the nearest foothills: the mainland horizon is only rarely visible behind a veil of clouds. Not the classic tropical landscape, but beautiful vistas nonetheless. Local knowledge and shallow draft let local boats move more nimbly than we could!

Overcast skies also make navigation difficult. The charts here are… wait, what charts?! Most of eastern San Blas just shows ‘unsurveyed’ on ours, and many visual piloting cues are absent in the overcast light and murky water. We move slowly and try to read each wavelet in the choppy water.

There’s a reef here just 3′ below the surface. See it? Yeah neither do we.

This is the area chosen for the Darien scheme, a Scottish effort to find the overland route to the Pacific: doomed not only to fail in transiting the isthmus, but to bankrupt many Scots and contribute to weakening the kingdom to the point it “united” with England. In a deep bay where St Andrews Fort once stood, a village with a handful of cane homes sits out on coral rubble over the reef.

To be continued…