“Those who fail to learn from history are

doomed to repeat it.” Sir Winston Churchill

It's beginning to look like 2013 may be a rough year for land-short accidents. Asiana 214 is still fresh and unexplained as this week's crash of a UPS Airbus A300 in Birmingham, Alabama adds to the mystery of seemingly healthy airliners crashing short of the runway.

The "how and why" of such accidents is the question everyone wants answered in hours...unfortunately it takes months to get the concrete answers we desire. But as work continues in San Francisco and Birmingham, the factors that led to other land short accidents are known and may hold clues that could shed light on current investigations. Today's post is Part II in a series…not intended to be an explanation of what happened to Asiana 214 or UPS 1354, but rather an overview of a seemingly similar accident.

Turkish 1951

The story begins... another airliner on an otherwise normal flight...another new pilot assisted by an instructor with a third set of eyes in the cockpit...another flight that ended in an oddly similar fashion as Asiana 214. Looking at the post-accident photos from Turkish 1951, the relatively short distance traveled after impact, the narrow field of debris and the separation of the tail were all factors that seemed to ring the bell of familiarity.

Turkish 1951 was a Boeing 737-800 landing at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport on February 25, 2009. Among the 135 passengers and crew on board, 9 people lost their lives. Among the dead were all three pilots and, ironically, three Boeing engineers... a fourth survived the accident. The first officer was new to the jet, still building required "Initial Operating Experience" while under the watchful eye of one of the company's most experienced pilots, a check-airman who occupied the left seat. The third pilot in the cockpit was designated as a "safety pilot" in place to monitor training of the first officer.

The first sign of trouble was a minor mechanical issue detected by the captain as the aircraft approached 8,000 feet above touchdown. As they neared Schiphol, the first officer, who was the pilot flying, reduced thrust to begin slowing the aircraft for landing. But as the throttles came back, an automated system issued a warning that indicated the aircraft was too low not to have the landing gear extended. The aircraft was well above the threshold for this warning...so why was it issued?

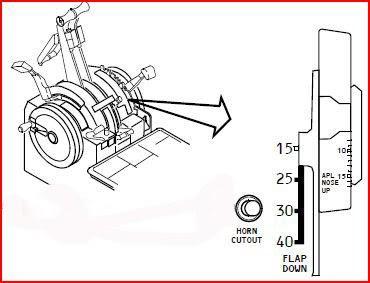

The Boeing 737 comes equipped with a warning system that protests loudly when certain unusual parameters are met. In addition to visual indications, a steady warning horn is provided to alert the flight crew whenever a landing is attempted and any gear is not down and locked. The “landing gear configuration” warning horn is activated by throttle and flap position as follows:

Flaps up through 10 degrees:

- Altitude below 800 feet Radio Altitude (RA) when either throttle set between idle and approximately 20 degrees throttle angle or an engine not operating and the other throttle less than 34 degrees. The landing gear warning horn can be silenced (reset) with the landing gear warning HORN CUTOUT Switch.

- If the airplane descends below 200 feet RA, the warning horn cannot be silenced by the warning HORN CUTOUT Switch.

- Either throttle set below approximately 20 degrees or an engine not running and the other throttle less than 34 degrees; the landing gear warning horn cannot be silenced with the landing gear warning HORN CUTOUT Switch.

- Regardless of throttle position; the landing gear warning horn cannot be silenced with the landing gear warning HORN CUTOUT Switch.

The captain quickly and correctly identified the fact that his radio altimeter was malfunctioning...actually indicating that the aircraft was on the ground...but the warning horn proved to be a distraction. I can tell you from experience that one of the greatest distractions for a pilot is a horn, light or annunciation that doesn't make sense. The airplane was well outside the parameters that should have activated the gear warning horn, but the horn sounded every time the throttles were reduced. The captain silenced the warning each time by pressing the HORN CUTOUT switch located on the throttle quadrant, but it would have been a constant distraction causing the pilots to second guess their instruments as they got closer and closer to the ground.

The issue with the landing gear horn is one that I've experienced many times myself and is not an issue that, in and of itself, should have resulted in an accident. It was, however, another link in the chain of events that led to this accident.

The next link was the approach itself. After examining Air Traffic Control, cockpit voice and radar recordings, it was determined that approach controllers had set the crew up for what pilots commonly refer to as a "slam dunk" approach. Simply put, a slam dunk occurs when the aircraft approaches the airport too high and too fast to execute a normal profile. If a pilot sees this coming, he will most likely begin to slow and configure for landing early. But if cleared to descend too late or vectored toward the airport earlier than expected, it can be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to get the jet down and at the appropriate speed in time to meet required stabilized approach requirements.

A stabilized approach is one in which the aircraft is at the appropriate speed, fully configured for landing (flaps and gear in landing positions) and on glide path with stabilized thrust by the time the jet reaches 1,000 feet.

A normal sequence of events would have an aircraft lined up with the runway and leveled off well before the point where the pilot would initiate final descent for landing. The time spent in "straight and level" flight allows the pilot to slow his aircraft and begin configuring for landing...but that isn't what happened. With flight 1951 descending at a higher than normal rate, the pilots were forced to intercept the glide path from above instead of below and were unable to meet stabilized approach requirements by the time they reached 1,000 feet above touchdown. Most airlines require their pilots to initiate a go-around in this scenario, but the Turkish pilots elected to continue.

Additionally, since the airplane was not fully configured, the captain was still working to complete the before landing checklist as the aircraft descended through 1,000 feet. With the captain distracted by the checklist, the safety pilot distracted by a last minute PA announcement to the flight attendants and the first officer distracted by an unusual approach and a nuisance warning horn, none of the three noticed that the airplane, which still thought it was closer to the ground than it actually was, was reducing thrust in preparation for landing. Normally, with the autothrottle engaged, this happens automatically at 27 feet above the runway. The throttles automatically retard and the pilot pulls back on the controls to reduce his rate of descent...this causes airspeed to decay just before touchdown. What the pilots didn't notice was that the autothrottles were reducing thrust while the jet was still hundreds of feet in the air. With the throttles at idle, airspeed quickly bled off as the aircraft came dangerously close to a stall.

As this happened, there would have been multiple warnings that the flight crew should have noticed. First, the pilot flying should have had his hands on the throttles and should have noticed when they began to retard prematurely. Unfortunately, the autothrottle system went into landing mode as the pilots were high and fast and trying to get down and slow down...the reduction in thrust was masked by the fact that the throttles were already at idle.

If any of the pilots had been looking at the airspeed indicator, they would have noticed the loss of airspeed and would have observed the speed pointer dip into a red and black warning zone depicted on the primary flight display (see video below). As speed continued to roll back, the white box around the airspeed would have changed colors and flashed. The sound of air rushing past the airplane would have decreased and the nose would have pitched up in an attempt to maintain the glide path...none of the three pilots noticed. As flight 1951 neared 400 feet above the ground, the effect of all the missed warning signs culminated with a stall too close to the ground to recover.

The video below is from YouTube and I don't know the pilots who flew or filmed it. Clearly, it was filmed in a flight simulator and the event in the video is significantly more violent than what was experienced by the pilots of flight 1951...right up to impact of course. The video shows the visual warnings available to Boeing 737 pilots during both high and low speed events. If you watch the speed tape on the left side of the screen, you will eventually see the speed box turn yellow and flash as airspeed decreases. Airspeed also dips well into the low speed range as depicted by red and black boxes. The green arrow extending from the speed box is a trend vector that predicts where airspeed will be in 10 seconds.

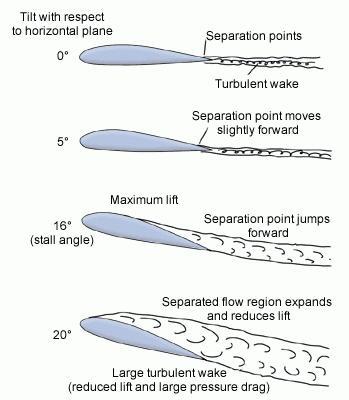

For some, the term stall may be confusing. In aviation, the word refers to the lack of sufficient airflow over the wing to sustain lift (see picture below). Stall recognition and recovery techniques are taught to pilots in the earliest stages of flight training. The maneuvers are also practiced by airline pilots in the simulator every time they return for recurrent training. If an actual stall condition is experienced while flying the real airplane, pilots are taught to “recover at the first indication of a stall,” but for training purposes, we are often required to demonstrate our ability to recover from a fully developed stall. One of the hardest things to do when training in the simulator is to fly through all the warnings. Even with a distracted and inexperienced pilot, I struggle to understand how the pilots of Turkish 1951 missed the warning signs.

As the last warnings of an impending stall sounded in the cockpit, the captain took over the controls, forcefully pushed the throttles forward and announced that he had control of the aircraft...but he took action too late and was unable to avoid falling from the sky.

As with just about any accident, a chain of events led up the crash of Turkish 1951...the removal of any one of the links in that chain would likely have changed the end result. The pilot flying was new and inexperienced on the jet. The pilots allowed themselves to be slam dunked onto the approach and intercepted the glide path from above. They neglected to go around when they failed to meet stabilized approach criteria. All three pilots were distracted by a mechanical abnormality and failed to notice warnings of an impending stall. Finally, the captain was distracted by conflicting duties to finish the before landing checklist and monitor the progress of his student. All together, the scenario proved too much to overcome.

Similarity to the Asiana crash?

Personally, I see a lot of similarities between these two accidents. The experience level and number of pilots on board is similar. The approach profile is almost identical. The transition from high and hot to low and slow on the approach is also the same and the impact short of the runway and disposition of the wreckage bear striking resemblance. The pilots of both aircraft were presented with ample warning that their jets were slowing below appropriate speeds and both crews failed to notice the warning signs.

Admittedly, the "how and why" investigation into the Asiana accident is far from over and many of the facts are not yet known. In San Francisco, there does not appear to have been any mechanical deficiency with the aircraft, but the approach landing system was not working as designed. Conversely, there was nothing mechanically wrong with the approach landing system in Schiphol, but the Turkish aircraft had a mechanical issue distracting the pilots. While both flights had similar issues...none should have been insurmountable hurdles for the pilots to overcome.