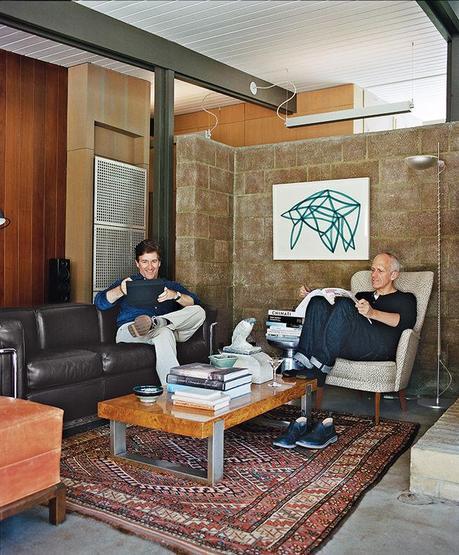

For their A. Quincy Jones house in Los Angeles, architect Bruce Norelius and his partner, Landis Green, retained and restored core elements, such as the living room’s redwood paneling and concrete-block wall.

Project Crestwood Renovation Architect Bruce Norelius A. Quincy JonesA. Quincy Jones designed some of the most dazzling midcentury houses in California, including Sunnylands—Walter and Leonore Annenberg’s vast estate outside Palm Springs—and the Brody House, in Los Angeles’s Holmby Hills. Ellen DeGeneres and Portia de Rossi bought and sold the Brody House last year, perpetuating Jones’s reputation as an architect who catered to the wealthy.

In fact, Jones was determined to prove “that modern architecture could be available at every income level,” says Cory Buckner, author of the book A. Quincy Jones. In the late 1940s, Jones set out to improve the quality of tract housing by helping to create a planned community in Brentwood, a neighborhood in Los Angeles. Called Crestwood Hills, it was intended to contain 500 houses: 160 were built, and only 33 survive.

One of those came on the market in 2009, when the daughters of the original owners decided it was time to sell. Meanwhile, Bruce Norelius, an architect, and his partner, Landis Green, a school administrator, were looking for a house in Brentwood. They had moved from Maine to California when Green became the head of a local private school called Wildwood (which recently hired the adventurous Los Angeles architect Neil Denari to update its campus).

Slideshow

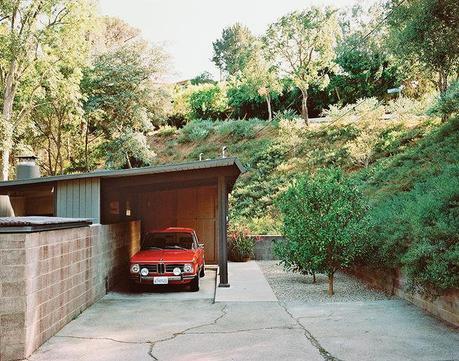

The carport leads to the entrance.

According to Norelius, when they saw the house in Crestwood Hills, “it felt like home.” This was despite the fact that it was small—less than 1,200 square feet—and had become, he says, “a little tired, with powder-blue carpeting and heavy draperies,” as well as countless coats of paint. The couple knew that they would have to make cosmetic changes but that they “wouldn’t be tearing down any walls.” Buying from the family of the original owners underscored their responsibility to maintain the building in as close to its original form as possible.

Luckily, they loved that original form. Though the rooms are small, they are enhanced by what Norelius calls Jones’s “rigor and economy.” For instance, the posts that support the roof beams also act as doorjambs, eliminating the need for separate framing. Similarly, the roof sheathing, of Douglas fir, is also the ceiling’s finish surface. In Jones’s post-and-beam scheme, Norelius says, “nothing is wasted.”

The first of the three bedrooms became the master, the second the guest room, and the third Norelius’s West Coast office (he also has a studio in Maine). The living-dining room feels large because of its connection to the outdoors. For parties, “we throw all the glass doors open, and everybody congregates outside,” says Green. They augmented the landscape, adding acacia, olive trees, and rosemary. “It’s a very stripped-down palette,” says Norelius, and also one that uses very little water.

Inside, Norelius explains, the couple “replaced some of the really sad plywood with new plywood, a straight-grain vertical fir.” They redid the kitchen, installing white-marble countertops and cabinets of oiled and waxed cold-rolled steel. Those aren’t materials Jones would have chosen, but, Norelius notes, “I believe he designed these houses to be living things. They’re not museums, and though I don’t want to change the bones, this isn’t a historical restoration.”

Slideshow

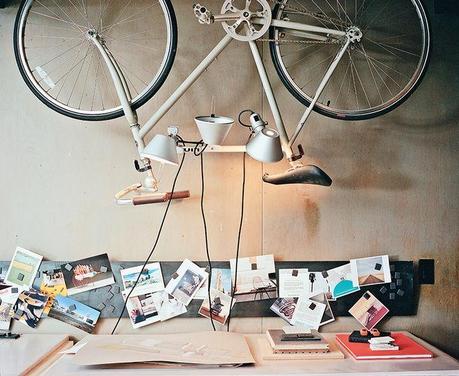

One of the bedrooms became Norelius’s studio, which includes lighting from Artemide above a custom desk.

New owners of midcentury houses often apply white paint to everything, but not Norelius and Green. As Norelius recalls, “We started stripping off white paint, [and] the browns of original timbers and the grays of concrete block were exposed.” That made the interiors darker. “We’re people who love light,” he says. “But the dark palette is so comforting. It makes the house feel like a shelter.”

Some of their neighbors are “A. Quincy Jones groupies,” Norelius says. “They know where the hardware for the kitchen cabinets was made.” Though he and Green haven’t quite achieved this level of devotion, they have been faithful to the architect’s intent. “We take our roles as stewards of this house seriously,” he says, “but what really strikes us every single day is how much fun we’re having living in it.”