Our kids come first – how often is this heard? From parents, politicians, and do-gooders alike. Children are our future; we should invest in them, with programs like pre-K.

We do know that the first months or years in a child’s life are crucial influences on the future person and his or her success. Recall the famous “Marshmallow Test” – if a young child has the self-discipline to defer gratification for the sake of later rewards, this is a powerful predictor of flourishing in school and life. Pre-K education has also been shown very helpful in a person’s future trajectory. Modest societal investments like this, in youngsters, deliver huge returns – making productive citizens who contribute to society, as opposed to losers and criminals who detract from it and soak up resources.

But we actually should take it one level back. What’s the biggest influence on a child’s earliest years? Parents. Differential parenting is a huge explanatory factor for the kinds of people we become. And let’s be frank: parenting styles tend to differ greatly among social classes. For example, it’s estimated that by age 3, kids in lower socio-economic homes hear

30 million fewer spoken words than in affluent homes – and in the former, more of the words are discouraging rather than encouraging. Such factors tend to perpetuate divergent social outcomes from generation to generation.

So Pre-K is all well and good, but we need Pre-pre-K: early education for

parents. Teaching them how to break out of dysfunctional ancestral patterns, to equip their kids to pass the Marshmallow Test, and so forth. I can’t claim this as my own brilliant idea; in fact such programs do exist, notably at Harlem Children’s Zone. Investments in such efforts would generate gigantic future dividends, both economically and in quality of life.

As an example, The Economist recently noted a program in Jamaica teaching mothers of chronically malnourished youngsters how to play with them in ways that promote verbal and physical skills. Those kids grew up to earn higher incomes than “untreated” kids – even those who had not been malnourished.

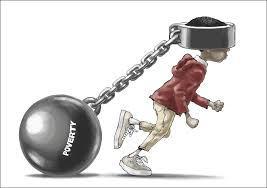

The Economist was making a broader point about poverty. Many conservatives think the poor are basically responsible for their situation, while progressives blame society. Conventional economics suggests that the answer is to give people opportunities to earn their way out of poverty, and many millions have indeed done so. But it’s not quite that simple; poverty has a tendency to be self-perpetuating because of its behavioral effects.

Poor people often make bad economic decisions, not because they are irrational or foolish, but because they lack access to the necessary information; their poverty may make them feel powerless as well as overly risk-averse; and the resulting stressful existence is not conducive to calm deliberation. They also face structural obstacles – as I’ve written, it’s costly to be poor.

The Economist points out that whereas traditional anti-poverty programs stress supplying resources, a behavioral approach focuses instead on how choices are made and how they can be improved. For instance, sending kids to school should be a no-brainer for their future well-being; yet in many poor countries, parents often don’t send them; however, some Latin American programs giving cash payments to those who do have dramatically boosted school attendance.

There’s some truth in the old saw about giving people fish versus teaching them to fish. But teaching fishing may not be enough. People may need to be taught to

want to fish.