I was fortunate enough to have visited sites that are of primary importance to Dr. Jose P. Rizal this year, which is also his sesquicentennial birth anniversary. I have also included excerpts from the authoritative collection of essays by Ambeth R. Ocampo, Rizal without the Overcoat. First, I begin in his birthplace and hometown, Calamba, Laguna. I then fly to where he was exiled in Dapitan, Zamboanga del Norte, and finally, I see where he was incarcerated and ultimately executed by firing squad in Manila. Our national hero was born seventh of the 11 children of prosperous farming parents, Francisco Mercado Rizal and Teodora Alonzo y Quintos. Dr. Rizal was born in the then Domincan-controlled town of Calamba, Laguna, and this is where we begin. Read more… LIFE: CALAMBA, LAGUNA

I was fortunate enough to have visited sites that are of primary importance to Dr. Jose P. Rizal this year, which is also his sesquicentennial birth anniversary. I have also included excerpts from the authoritative collection of essays by Ambeth R. Ocampo, Rizal without the Overcoat. First, I begin in his birthplace and hometown, Calamba, Laguna. I then fly to where he was exiled in Dapitan, Zamboanga del Norte, and finally, I see where he was incarcerated and ultimately executed by firing squad in Manila. Our national hero was born seventh of the 11 children of prosperous farming parents, Francisco Mercado Rizal and Teodora Alonzo y Quintos. Dr. Rizal was born in the then Domincan-controlled town of Calamba, Laguna, and this is where we begin. Read more… LIFE: CALAMBA, LAGUNA You see, the Rizals were not really landowners. They were tenants of the Dominicans who owned most of the land in Calamba. According to the Rizals (the Dominicans have their own version of the story), the tenants started to complain about rent increases that did not consider whether the harvest for that season was good or not… Rizal was not a radical man, but in 1891, he became a for these tenants whom he advised to trust in the justice and goodness of Mother Spain. The tenants did just that, and the Spanish governor-general, Valeriano Weyler (who became notorious as the Butcher of Cuba), sent soldiers to bodily evict the hardheaded tenants from Calamba…It was a major upheaval for the people of Calamba and also Rizal, who became a marked man not only for his anti-clerical novel, Noli me tangere, but also for being in the center of a major agrarian dispute. –Rizal’s New Calamba in Sabah

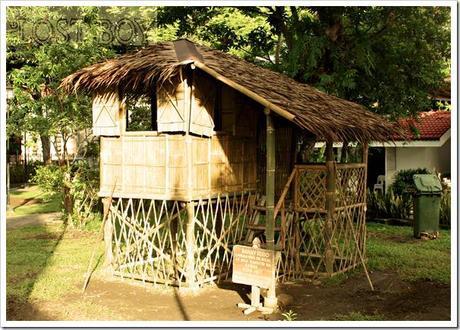

Rizal Shrine in Calamba, Laguna is a 1949 replica of the original house where our national hero was born on June 19, 1861. The original house, built after Dr. Rizal’s parents married in 1848, adapted Spanish architectural design and was one of the first stone and hardwood houses in Calamba. The house was symbolic of the Rizal family’s well-off status. Managed by the National Historical Institute, the replica house showcases some colonial furniture and kitchenware, as well as Dr. Rizal’s clothes, paintings, sculptures, and laminated excerpts of written works. Below is a replica of a nipa hut where young Dr. Rizal used to play.

Rizal Shrine in Calamba, Laguna is a 1949 replica of the original house where our national hero was born on June 19, 1861. The original house, built after Dr. Rizal’s parents married in 1848, adapted Spanish architectural design and was one of the first stone and hardwood houses in Calamba. The house was symbolic of the Rizal family’s well-off status. Managed by the National Historical Institute, the replica house showcases some colonial furniture and kitchenware, as well as Dr. Rizal’s clothes, paintings, sculptures, and laminated excerpts of written works. Below is a replica of a nipa hut where young Dr. Rizal used to play.  How to get there: Calamba City is a little over an hour’s drive from Manila via South Luzon Expressway. Buses to Sta. Cruz, Laguna from Cubao and Buendia will make a stop in Calamba Crossing. From there, a jeepney or tricycle can be taken to “bayan” or city center. (Google Maps) EXILE: DAPITAN, ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE

How to get there: Calamba City is a little over an hour’s drive from Manila via South Luzon Expressway. Buses to Sta. Cruz, Laguna from Cubao and Buendia will make a stop in Calamba Crossing. From there, a jeepney or tricycle can be taken to “bayan” or city center. (Google Maps) EXILE: DAPITAN, ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE Sometimes I cannot make sense of Rizal. Was he happy in Dapitan? In 1893, he wrote Blumentritt and described a typical day: “I have three houses: a square house, a six-sided house, and an eight-sided house. My mother, my sister Trinidad, and a nephew and I live in the square house; my students—boys who I am teaching math, Spanish and English—and a patient [in the six-sided house]. My chickens live in the six-sided house. From my house, I can hear the murmur of a crystalline rivulet that drops from high rocks. I can see the shore, the sea where I have two small boats or barotos, as they are called here. I have many fruit trees: mangoes, lanzones, guyabanos, batuno, langka, etc. I have rabbits, dogs, cats, etc. I get up early, at 5 in the morning inspect my fields, feed the chickens, wake up my farm-hands and get them to work. At half past 7, we have breakfast consisting of tea, pastries, cheese, sweets, etc. Then, I hold clinic examining patients and training the poor patients who come to see me. I dress and go to town in my baroto to visit my patients there. I return at noon and have lunch that has been prepared for me. Afterwards I teach the boys until 4 and spend the rest of the afternoon in the fields. At night, I read and study.” Although Rizal did not live behind bars, Dapitan was not London, Paris, New York or Madrid. Dapitan was literally the boondocks. —Rizal’s poetry in Dapitan

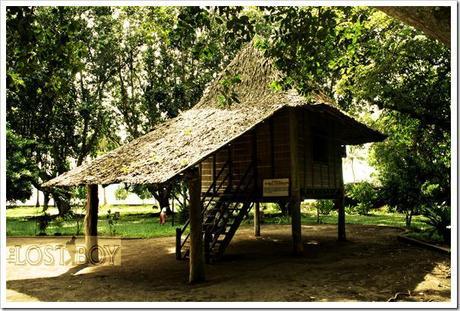

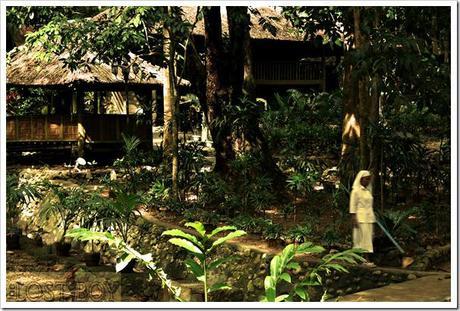

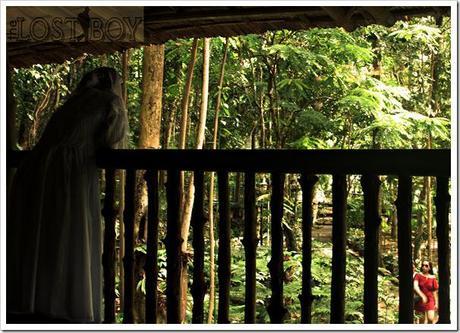

Dr. Rizal was exiled in Dapitan in July 1892 after being implicated in nascent rebellion. Through his shared lottery winnings, he was able to procure a parcel of land near the shore of Talisay in March 1983. During his exile, he was a farmer, entrepreneur, educator, inventor, painter, sculptor, archaeologist, linguist, grammarian, architect, poet, biologist, composer, surveyor, environmentalist, and most importantly, a practicing physician. While sequestered by the Spaniards on January 15, 1897 as part of indemnity to Spain, Dr. Rizal’s 16-hectare estate in Talisay, Dapitan was converted in 1913 and eventually reconstructed into a sprawling park in his memory. Then Commonwealth President Manuel L. Quezon by virtue of Proclamation No. 616 declared it as “Rizal National Park” in 1940.

Dr. Rizal was exiled in Dapitan in July 1892 after being implicated in nascent rebellion. Through his shared lottery winnings, he was able to procure a parcel of land near the shore of Talisay in March 1983. During his exile, he was a farmer, entrepreneur, educator, inventor, painter, sculptor, archaeologist, linguist, grammarian, architect, poet, biologist, composer, surveyor, environmentalist, and most importantly, a practicing physician. While sequestered by the Spaniards on January 15, 1897 as part of indemnity to Spain, Dr. Rizal’s 16-hectare estate in Talisay, Dapitan was converted in 1913 and eventually reconstructed into a sprawling park in his memory. Then Commonwealth President Manuel L. Quezon by virtue of Proclamation No. 616 declared it as “Rizal National Park” in 1940.  Currently, the park boasts of replicas, including the dormitory of Dr. Rizal’s students, his house, kitchen, and bedroom. Likewise within the park is an exhibition of memorabilia. A group of Rizalistas also roam around and maintain the park grounds.

Currently, the park boasts of replicas, including the dormitory of Dr. Rizal’s students, his house, kitchen, and bedroom. Likewise within the park is an exhibition of memorabilia. A group of Rizalistas also roam around and maintain the park grounds.  How to get there: Two airlines service the nearby City of Dipolog (IATA: DPL). Philippine Airlines flies from Manila, and Cebu Pacific flies from both Manila and Cebu. From the airport or the city proper of Dipolog, buses ply the Dipolog-Dapitan route. From the bus terminal in Dapitan, the park is just a short tricycle ride away. Alternatively, OceanJet runs a daily fastcraft service to the port of Dapitan from Cebu via Tagbilaran, Bohol and Dumaguete, Negros Oriental. (Google Maps) DEATH: MANILA

How to get there: Two airlines service the nearby City of Dipolog (IATA: DPL). Philippine Airlines flies from Manila, and Cebu Pacific flies from both Manila and Cebu. From the airport or the city proper of Dipolog, buses ply the Dipolog-Dapitan route. From the bus terminal in Dapitan, the park is just a short tricycle ride away. Alternatively, OceanJet runs a daily fastcraft service to the port of Dapitan from Cebu via Tagbilaran, Bohol and Dumaguete, Negros Oriental. (Google Maps) DEATH: MANILA The slow walk to Bagumbayan began at 6:30 a.m. It was a cool, clear morning and Rizal was dressed, appropriately, in black. Black coat, black pants and a black cravat emphasized by his white shirt and waistcoat. He was tied elbow to elbow, but he proudly held up his head, crowned with the signature chistera or bowler hat made famous by Charlie Chaplin… He made one last request that the soldiers spare his precious head and shoot him in the back toward the heart. When the captain agreed, Rizal shook the hand of Taviel de Andrade and thanked him for the vain effort of defending him. Meanwhile, a curious Spanish military doctor came and felt Rizal’s pulse and was surprised to find it regular and normal. The Jesuits were the last to leave the condemned man. They raised a crucifix to Rizal’s face and lips, but he turned his head away and silently prepared for death. As the captain raised his saber in the air, he ordered his men to be ready and shouted, Preparen! The order to aim the rifles followed: Apunten! Then, in split second before the captain’s saber was brought down with the order to fire Fuego!, Rizal shouted the two last words of Christ, Conssumatum est! (it is done). The shots rang out, the bullets hit their mark and Rizal made that carefully choreographed twist he practiced years before that would make him fall face-up on the ground. –“Oh, what a beautiful morning!”

To prove his dissociation from the revolution, Dr. Rizal sought and was granted permission by Governor-General Ramon Blanco to be sent to Cuba from Dapitan to treat those with yellow fever. However, Dr. Rizal was arrested en route to Cuba, incarcerated in Barcelona, and sent back to Manila. He was imprisoned in Fort Santiago while standing for trial. He was associated with members of the Katipunan, which made him as their honorary president without his knowledge. The Spaniards further presented evidence proving Dr. Rizal’s “involvement” in the Katipunan, among them: his picture hung in meeting places, his name used as password, and his name called in their battlecry. He was found guilty by the Spaniards of rebellion, sedition, and conspiracy and was condemned to death by firing squad.

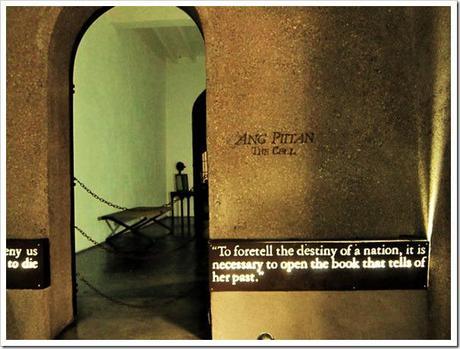

To prove his dissociation from the revolution, Dr. Rizal sought and was granted permission by Governor-General Ramon Blanco to be sent to Cuba from Dapitan to treat those with yellow fever. However, Dr. Rizal was arrested en route to Cuba, incarcerated in Barcelona, and sent back to Manila. He was imprisoned in Fort Santiago while standing for trial. He was associated with members of the Katipunan, which made him as their honorary president without his knowledge. The Spaniards further presented evidence proving Dr. Rizal’s “involvement” in the Katipunan, among them: his picture hung in meeting places, his name used as password, and his name called in their battlecry. He was found guilty by the Spaniards of rebellion, sedition, and conspiracy and was condemned to death by firing squad.  On December 30, 1896, at around seven in the morning, Dr. Rizal was shot, as described above, in Bagumbayan, which was later known as Luneta. His remains were initially buried in Paco Cemetery, pictured above, with no identification but was later exhumed to be properly and honorably interred under the mighty bronze and granite Rizal Monument in what is now known as Rizal Park. This was made possible by virtue of Philippine Commission Act No. 243 passed on September 28, 1901 under American rule. At present, Fort Santiago has a model of Dr. Rizal’s detention cell inside Rizal Shrine. Also on exhibit inside the shrine are Dr. Rizal’s overcoat, copies of his works, and his vertebra with a bullet embedded. Meanwhile, Rizal Park hosts a multitude of attractions, among them a One Stop Rizal Heritage Trail and a relief map.

On December 30, 1896, at around seven in the morning, Dr. Rizal was shot, as described above, in Bagumbayan, which was later known as Luneta. His remains were initially buried in Paco Cemetery, pictured above, with no identification but was later exhumed to be properly and honorably interred under the mighty bronze and granite Rizal Monument in what is now known as Rizal Park. This was made possible by virtue of Philippine Commission Act No. 243 passed on September 28, 1901 under American rule. At present, Fort Santiago has a model of Dr. Rizal’s detention cell inside Rizal Shrine. Also on exhibit inside the shrine are Dr. Rizal’s overcoat, copies of his works, and his vertebra with a bullet embedded. Meanwhile, Rizal Park hosts a multitude of attractions, among them a One Stop Rizal Heritage Trail and a relief map.  How to get there: Upon touchdown at Ninoy Aquino International Airport (IATA: MNL), metered taxis can take you for a short ride to Rizal Park, Fort Santiago, or Paco Park. Alternatively, jeepneys and buses in Manila are abundant and can take you to these three sites. (Google Maps) AFTERTHOUGHT Journeying through these three sights gave me a glimpse of how intricate, albeit fulfilling, the life our national hero is. This rewarding expedition through Dr. Rizal’s life and work can be summed up by his patriotic words: “I have always loved my poor country and I’m sure i shall love her until my last moment, should men prove unjust to me. I shall die happy, satisfied with the thought that all I have suffered, my life, my loves, my joys, my everything, I have sacrificed for the love of her.”

How to get there: Upon touchdown at Ninoy Aquino International Airport (IATA: MNL), metered taxis can take you for a short ride to Rizal Park, Fort Santiago, or Paco Park. Alternatively, jeepneys and buses in Manila are abundant and can take you to these three sites. (Google Maps) AFTERTHOUGHT Journeying through these three sights gave me a glimpse of how intricate, albeit fulfilling, the life our national hero is. This rewarding expedition through Dr. Rizal’s life and work can be summed up by his patriotic words: “I have always loved my poor country and I’m sure i shall love her until my last moment, should men prove unjust to me. I shall die happy, satisfied with the thought that all I have suffered, my life, my loves, my joys, my everything, I have sacrificed for the love of her.”  June 19, 2011 is the 150th Birth Anniversary of Dr. Jose P. Rizal. Celebrations and activities will be held nationwide, more notably in Calamba, Manila, and Dapitan. Everyone is enjoined to support this commemoration. For more details, click here.

June 19, 2011 is the 150th Birth Anniversary of Dr. Jose P. Rizal. Celebrations and activities will be held nationwide, more notably in Calamba, Manila, and Dapitan. Everyone is enjoined to support this commemoration. For more details, click here.  The Pinoy Travel Bloggers group holds a monthly Blog Carnival, wherein participating bloggers write about a singular theme. Mechanics and archives are found in Estan Cabigas’ Langyaw page here. For the month of June, we write about Rizal and Travel in recognition of our national hero’s sesquicentennial birth anniversary as hosted by Ivan Henares of Ivan About Town. Thanks to Brian Ong for allowing me to use his pictures from our tour of the Manila sites on the press launch of Lakbay Jose Rizal @ 150 last month.

The Pinoy Travel Bloggers group holds a monthly Blog Carnival, wherein participating bloggers write about a singular theme. Mechanics and archives are found in Estan Cabigas’ Langyaw page here. For the month of June, we write about Rizal and Travel in recognition of our national hero’s sesquicentennial birth anniversary as hosted by Ivan Henares of Ivan About Town. Thanks to Brian Ong for allowing me to use his pictures from our tour of the Manila sites on the press launch of Lakbay Jose Rizal @ 150 last month.