Sure, it’s a tough time for everyone, isn’t it? But it’s a lot worse for the already disadvantaged, and it’s only going to go downhill from here. I suppose that most people who read this blog can certainly think of myriad ways they are, in fact, still privileged and very fortunate (I know that I am).

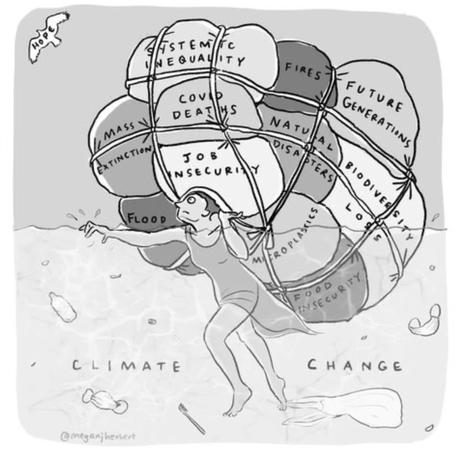

Nonetheless, quite a few of us I suspect are rather ground down by the onslaught of bad news, some of which I’ve been responsible for perpetuating myself. Add lock downs, dwindling job security, and the prospect of dying tragically due to lung infection, many have become exasperated.

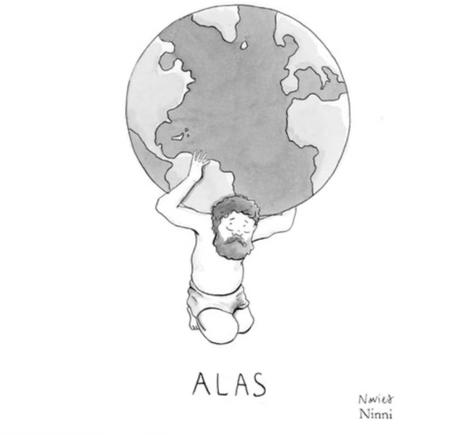

I once wrote that being a conservation scientist is a particularly depressing job, because in our case, knowledge is a source of despair. But as I’ve shifted my focus from ‘preventing disaster’ to trying to lessen the degree of future shittyness, I find it easier to get out of bed in the morning.

What can we do in addition to shifting our focus to making the future a little less shitty than it could otherwise be? I have a few tips that you might find useful:

- Remember that conservation biology is really the field that we don’t need a lot more of. Sure, we can refine our knowledge about biological mechanisms and phenomena, but these days conservation has become more of a psychological, social, economic, and behavioural science. If you want to make applied strides in the field, I highly recommend training outside of the strict confines of biology.

- Team up with a variety of different experts to tackle big problems. But don’t just make more priority maps; try instead to pick difficult problems and find tractable solutions using truly interdisciplinary approaches.

- Make sure your interdisciplinary team is composed of policy people from the outset. Ask them what they need to solve a problem, and then aim to find the solution they seek.

- I might sound like a broken record, but keep up and constantly improve your maths skills. Whether you’re modelling the climate, extinction patterns, human behaviour, or economic trends, a scientist’s job is decidedly more transferable to different ideas, datasets, and approaches when numeric expertise (and coding) is made a priority. That last point certainly applies to increase your employment prospects too.

- Think local. It’s unlikely that you’ll be flitting off to the remote corners of the planet to engage in some dashing and daring field work to save a jungle somewhere far from home. Not only is it high time for colonial attitudes to be purged from our field, the foreseeable future does not bode well for this type of unrestricted movement. Find your local issues, team up with experts around the corner, and take on tractable research questions.

- Count the little wins. In reference the previous point, make sure that you take note of even the smallest wins, even if it just involves changing one person’s ideas for the better.

- There’s more to life than academia. With universities everywhere under increasing financial stress exacerbated by a major reduction in international movements (especially in Australia where the former financial model of relying on foreign students to subsidise operations has turned out to be a rather awful idea). Think outside the box and target non-academic pathways as priority, rather than a second choice.

There are undoubtedly many other avenues to gain the upper hand on the feeling of desperation, and I’m keen to hear about different experiences that might benefit others.

I’ll share one thing that happened recently that slightly improved my otherwise largely misanthropic view of the world. A friend and colleague (who shall remain nameless, but he knows who he is) who worked at a university in Australia decided to step down from his tenured and professorial position to free up departmental finances that could be otherwise directed to younger staff with families. He didn’t have to do this, but early retirement suited him, and it certainly suited the university financially, and more importantly, supported earlier-career researchers in the department. Gestures like this are pure gold.

CJA Bradshaw