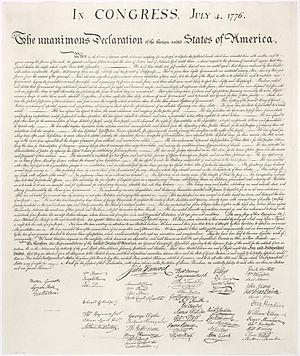

This is a high-resolution image of the United States Declaration of Independence (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

I seem to deal with this problem every 6 to 12 months. Someone reads what we’ve come to call the “Declaration of Independence” and sees that its proper name is “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America” and leaps to the conclusion the proper name for this country must be the “united States of America”.

Back in the 1990s, when I first saw the proper name for our “Declaration of Independence,” I leaped to the very same conclusion. I thought, “Damn! The proper name for this country must be ‘united States of America’!!! No wonder we’re having so much trouble in court! We don’t even understand the proper name of our own country!!!

But over time, I realized that my conclusion (the proper name for this country is the “united States of America”) was mistaken. That conclusion is a “rookie” mistake and I suppose that all of us who study our country’s political and legal foundation have already made it or are destined to make it at some point in the future.

• For example, here’s a recent comment on my blog:

“I am surprised you did not pick up on or comment on the uncapitalized “u” in the word “united” in the original document and correctly reproduced in the early printings of the Declaration.

Given that I’ve addressed this issue in the past on radio shows, or in my former magazine (“AntiShyster”), and probably on this blog, I was a little bit surprised that I felt “compelled” to write a reply.

But sometimes, it’s as if the Good LORD makes me read things I don’t want to read, or respond to things I personally don’t want to respond to. I don’t hear a voice. It’s not an absolute “compulsion”. It’s just something like getting a sudden “taste” for a Snickers bar. Something inside me suddenly tells me I should have a Snickers bar—or in this case, I should reply to a comment about the “united States of America”.

I know that Snickers bars aren’t really good for me. It’s old news (to me) that “united States of America” is sometimes mistakenly taken to be the proper name for our country. I’m a busy (or confused) man. So, I’ve got better things to do than waste my time responding the “united States of America” issue. Been there. Done that. Several times.

And yet, there was that darned “inclination” to respond to a comment that I didn’t want to respond to. So I started writing a response and, as usually happens whenever I get one of these “inclinations,” I was much surprised to find myself learning something that might be important.

The Good LORD never wastes my time. It seems that he’s doing so almost every time I get one of this “inclinations”. But I always learn something—as I did today when I replied to the previous comment on “united States of America”.

• For whatever it’s worth, my primary motive for writing this blog is not to educate my readers, but to educate myself. I learn by writing. The slow, pedantic process of writing forces me to slow down and patiently consider some idea that I presume to already understand.

I write. I slow down. I take time to look and consider. And if I’m lucky (or blessed), I suddenly “see” new insights that I had not previously imagined.

For me, writing is not simply a way of speaking and telling what I already know to others. Writing is a way of hearing and learning insights that may flow from “what I already know”. That’s why writing fascinates me. It’s like going up a nearby creek to pan for gold. I don’t always find “gold” when I write, but I’m always excited by the possibility.

Writing is not the means by which I try to help educate my readers and tell them what I think. Writing is the means by which I help educate myself and learn things that I otherwise have not yet perceived. So when I get that sudden “inclination” to write on a subject (like, “united States of America”), I am usually and initially annoyed by the diversion, but I always follow through in hopes of finding another small nugget of gold (or maybe fool’s gold?).

• So I responded to the comment on “united States of America” as follows:

I picked up on the lower-case “u” in the word “united” in “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America” (which has come to be referred to as the “Declaration of Independence”) probably about 15 years ago. Maybe more.

The word “united” is not capitalized because it’s used as an adjective (as is the other “u”-word, “unanimous” and also the word “thirteen” in the title of that document) rather than as part of a proper name. There was no single entity named “The United States of America,” or “United States of America” or even “United States” on July 4th, A.D. 1776. Therefore, it would’ve been improper to capitalize the world “united” as if it were part of a proper noun/proper name.

Such entity was not created until five years later, in A.D. 1781, when the Articles of Confederation first created a confederation and perpetual Union that was expressly named “The United States of America”.

The “Declaration” of July 4th, A.D. 1776 merely created thirteen separate and independent States that were no more united into a single political entity than China and Brazil are today. Nevertheless, on July 4th, A.D. 1776, these thirteen independent States or “countries” were acting in a “united” fashion by drafting the “Declaration of Independence”. While those thirteen new States were acting in a “united” manner, they were doing so just like thirteen completely separate States or countries (like Brazil and China) might agree to act in concert in a treaty.

(Damn! There’s my “daily nugget”. I won’t say that it’s absolutely true, but it’s at least arguable that the nature of our “Declaration of Independence” is that of a treaty! That hypothesis might not strike y’all as particularly insightful, but as you’ll read, it just might be.)

As of July 4th, A.D. 1776, these thirteen new States/countries were not “united” into a single political entity similar to the singular nation composed of several formerly independent countries that was once called the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics”—USSR.

Because the newly-created, thirteen States had not yet been joined into a single “country,” they had no single, proper name such as “The United States of America,” “United States of America” or even “United States”. Therefore, as used in “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,” the word “united” was used as an adjective and properly and necessarily lower-case.

I’m grateful for the reader’s comment on “united States of America” because, in responding, I realized that the “Declaration of Independence” might be properly understood to be the first treaty among the thirteen, newly-created but independent States.

• Up until now, I’d thought that the only proper way to access the God-given, unalienable Rights declared in the “Declaration of Independence” was through the 9th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States which declares,

“The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

In other words, while the Constitution might expressly declare or enumerate several “rights” (as in the Bill of Rights), that enumeration could not be presumed to be complete. Other rights existing at the time of the Constitution’s ratification would continue to exist and be recognized by the government even though they were not expressly mentioned in the Constitution.

Therefore, if you wanted to claim any of the God-given, unalienable Rights declared in the “Declaration of Independence” you must first identity yourself as one of the “people” of the several “United States” and/or of “The United States of America,” and claim your God-given, unalienable Rights (such as Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness—but there are others) by means of the 9th Amendment.

But today, for the first time, I realize that “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America” might be viewed as not only the document that created those first thirteen States, but perhaps also as the first treaty among those first thirteen States.

• Trying to describe the nature of our “Declaration of Independence” raises a peculiar question: What, exactly, is that document?

Technically, it “incorporated” the first thirteen States. Is it therefore properly described as a “corporate charter”? (Thirteen corporate charters rolled into one?)

But it also dissolved the “political bands” that had previously bound the pre-existing colonies to Great Britain. Does that make it some sort document of “corporate dissolution”?

Or was it a document that specified all of the breaches of trust committed by King George, and was therefore intended to be an official “notice” of the dissolution of the previous trust relationship between the colonies and Great Britain?

In truth, the “Declaration” accomplished several different objectives that might otherwise have been achieved by means of several different instruments.

I.e., for the sake of clarity, the first instrument might’ve officially terminated the contractual and/or fiduciary relationship of each of the thirteen colonies to Great Britain.

A second instrument might’ve officially created each of the thirteen States out of the former colonies and included a declaration of the principles (“All men are created equal,” etc.) on which each new State was bound to act.

A third instrument might’ve been expressly described as the first “Treaty” between the newly formed, independent States to act in concert in their separation from, and war with, King George.

However, instead of complicating things by drafting several documents, the Founders wrote a “Declaration of Independence” that (when supported by firearms) achieved several objectives simultaneously.

The simplicity—and political expediency—of drafting a single inspiring “Declaration” instead of several tedious legal documents—served the Founders well. But it also left some confusion as to the essential nature of the “Declaration” for future generations (or at least, for me).

• But let’s suppose that today’s “nugget” (that the “Declaration of Independence” was a treaty) is correct.

What’s the significance? What’s the big deal?

Well, if the “Declaration” was the first treaty among the several States when they existed as separate countries, then it may be that—in addition to accessing our God-given, unalienable Rights by means of the 9th Amendment—we can also access those rights under one or more of the four clauses in the Constitution that apply to treaties.

Those four clauses are Articles: 1.10.1 (State prohibition to make); 2.2.2 (presidential power to make); 3.2.1 (court jurisdiction); and, 6.2 (supremacy clause):

Article 1.10.1: “No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation . . . .” This prohibition applies to States of the Union only after the Constitution was ratified in A.D. 1788. It has no bearing on any treaties entered into prior to ratification of the Constitution. Thus, treaties entered into by the States even before they created the perpetual Union with the Articles of Confederation of A.D.1781 would remain valid and effective. If it were true that the “Declaration” were a treaty in A.D. 1776, it would still be a treaty today.

Article 2.2.2: The President “shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; . . . .” Since the Constitution was ratified in A.D. 1788, only the President has power to “make Treaties”. That post-1788 restriction has no bearing on the legitimacy of a treaty entered into by the States in A.D. 1776.

Article 3.2.1: “The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law or Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made under their Authority; . . . .”

If this clause had only referenced “treaties which shall be made,” the judicial power of the Article III courts would only apply to those treaties made after the Constitution was ratified in A.D. 1788 and would not apply to the “Declaration”/treaty of July 4th, A.D. 1776.

However, because Article 3.2.1 includes the express phrase “and Treaties made,” the judicial power extends to treaties “made” (past-tense) prior to the ratification of the Constitution in A.D. 1788.

If it were true that the “Declaration” is a treaty, then it should follow that any lawsuit that implicates the “Declaration” and/or the God-given, unalienable Rights declared therein, should open the door to being heard in an Article III, judicial court of the United States.

Thus, it appears possible that if any plaintiff or defendant raised the “Declaration” and his God-given, unalienable Rights as part of his petition or defense, that the only court that might have jurisdiction over that case would be an Article III court of the United States.

Do you begin to see why the hypothesis that the “Declaration” is a treaty could be important?

Consider: suppose you were issued a mere traffic ticket and you found a legitimate basis to invoke the “Declaration of Independence” and/or your God-given, unalienable Rights as part of your defense. Could you thereby challenge and perhaps even defeat the jurisdiction of the municipal court? If cases involving treaties can only be heard by an Article III court, your local municipal court would seemingly lack jurisdiction to hear such cases. In fact, even your state, administrative and territorial courts might have no jurisdiction to hear a case involving a treaty.

As a plaintiff, trying to even find (let alone access) an Article III court under the Constitution is difficult if not impossible. We used to have “District Courts of the United States” under Article III of the Constitution. We now have “United States District Courts” which are not Article III/judicial in nature, but are instead “territorial” courts probably operating under the authority of Article 4.3.2 of the Constitution (exclusive legislative jurisdiction of Congress over the territories).

I have no clear idea as to how to open an Article III judicial court as a plaintiff. There are a couple of theories on how to do so, but I don’t know if anyone can actually do it.

However, if I were an alleged defendant in a case, and my first answer: 1) invoked my status as one of the “people” of “The United States of America”; 2) made a claim on my God-given, unalienable Rights; and 3) invoked both the 9th Amendment and Article 3.2.1—I might be able to challenge the jurisdiction of whichever trial court had been invoked by the plaintiff. If I could do so successfully, I might be able to put the plaintiff in the untenable position of trying to find an Article III (judicial) court to hear his petition. The cost and inconvenience (and potential impossibility) of invoking an Article III court might be sufficient to dissuade the plaintiff (or even prosecutor) from proceeding with his case.

This is all conjectural. If the strategy as outlined was potentially effective, it wouldn’t be easy to implement and the “system” might work mightily to prevent the strategy from succeeding. On the other hand, if the strategy were invoked very early in any proceeding and presented in way that seemed likely to succeed, there’s a good chance that the plaintiff/prosecutor would drop the case rather than take a chance on losing and making some explosive precedent.

Article 6.2: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”

If the “Declaration” is a treaty, then under the supremacy clause (Article 6.2) of the Constitution, it’s part of the “supreme Law of the Land” and the “Judges in every State shall be bound thereby”.

The problem here is that the supremacy clause applies to judges “in every State” of the Union. It does not apply to judges acting in territories. If it’s true that “The State of Oregon” is the proper name for a State of the Union while “STATE OF OREGON,” “Oregon,” or “OR” signify a territory, then the “territorial” judges of “STATE OF OREGON,” “Oregon,” and “OR” are not subject to the supremacy clause.

If so, a plaintiff or defendant can probably not access the “Declaration” as a treaty under the “supremacy clause” in a territorial court.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing.

If you invoked the “Declaration” under the “supremacy clause” in a territorial court of an apparent “state” (actually, territory) and did so with great skill, you might be able to compel that court to openly or at least implicitly admit that it is not a court of a State of the Union. I guarantee that that’s not an admission that any territorial court at the “state” level will be eager to make on the record.

More, even if such admission were made, it would open the door for a defendant to challenge the court’s jurisdiction on the basis that he and all of the acts, facts, evidence and alleged offenses took place within the venue of a State of the Union and therefore was not subject to the authority of a “territorial” court.

If the law gives you lemons, make citric acid.

• If you can’t use the supremacy clause (Article 6.2) successfully, you might try to also invoke the 9th Amendment to access your God-given, unalienable Rights.

But the 9th might also fail insofar as the Bill of Rights is only intended to protect the States of the Union and the people of the States of the Union from the federal government. If you failed to establish that you and the facts of your case were all within a State of the Union, and failed to refute that you and your acts took place in a territory like “TX” or “OR,” then you might not be able to make effective claims based on the 9th Amendment.

But, if the “Declaration” really is a treaty, that’s not necessarily bad for defendants if their defense also invoked Article 3.2.1 (“The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law or Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made,. . . .”). If we’re not in a State of the Union then, under Article 3.2.1, the door might swing wide open for a defense based on a treaty (the “Declaration”?) that could only be heard by an Article III (judicial) court.

• So, whatcha think? Do my “insights du jour” make any sense? Or are they fundamentally flawed in way that makes them illusory and without value?

Lemme know.