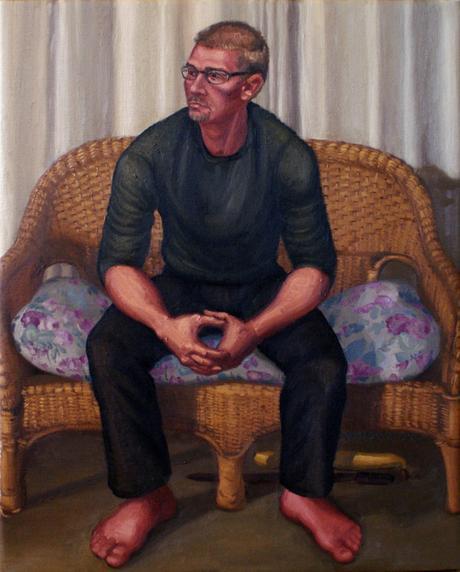

North (Bill Thomas) © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

I’ve been fortunate to be having some serious brain time with Ryan Daffurn and Scott Breton of late. We’ve been discussing, from our own viewpoints and languages, our common understanding of the role of the painter, which is to pull the visible world apart, inspect it, learn it, attempt to understand it, and then to reassemble our visual knowledge into constructed, tightly orchestrated images. Scott is perhaps most clear and persistent in his language, and I will adopt his term here: painting is about integration.

Ryan’s recent work is an ambitious amalgam of observation, collection, reinvention and imagination, in a manner I’ve found difficult to explain to others because they are not ready to hear such ideas. When people have seen his representational work, they have asked such questions as, ‘where is that?’ And I’ve realised that people are approaching realistic painting with a very limited perspective, thinking it can only be a rehashing of something once seen. In fact, the painting in question began with a fascination for a bizarre playground in Berlin, which lodged its oddity somewhere deep in the recesses of Ryan’s brain. It developed as he redrew it from memory, drawing little thumbnails and growing new exploratory configurations out of his brain, organically and freely. On transitioning to the canvas he referred to photos collected in Berlin, but these photos were always subordinated to his own design, and subjected to new physical constraints: the effect of an unnatural green light, like that accompanying a hail storm, completely imagined; the removal of black from his palette, to set hues off against each other more thoughtfully, to create a more meaningful colour contrast rather than an overbearing tonal one. In the end, ‘where’ is not really an inquiry relevant to this painting, which is ripe with fascinating things to talk about. But people are not primed to talk about these things, and it is to these things I hope we can redirect their attention.

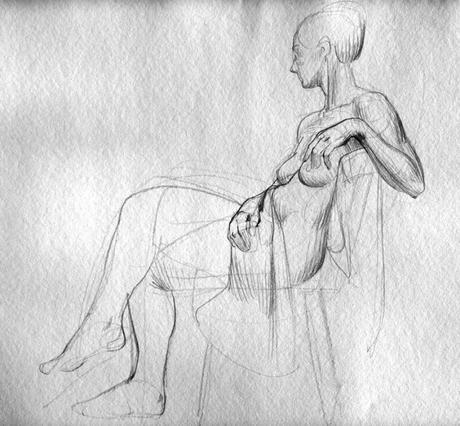

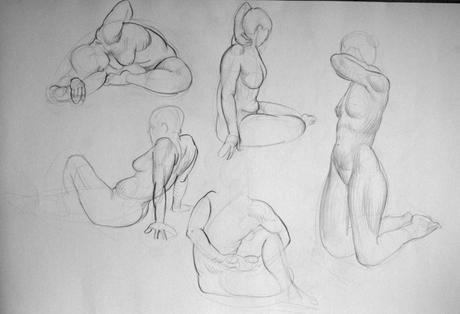

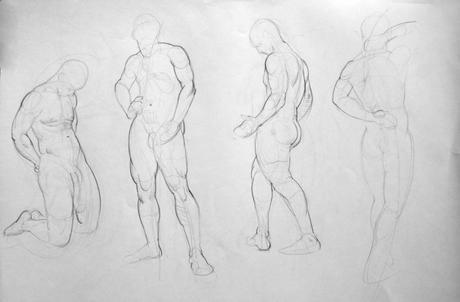

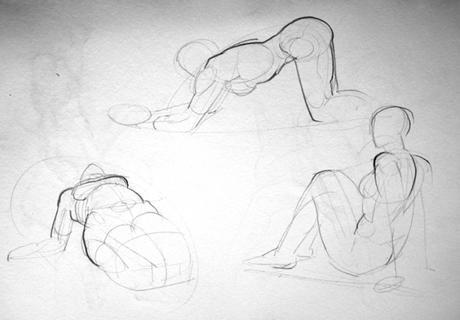

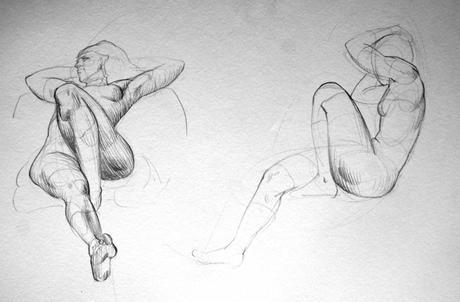

We are drawing from the model regularly, and returning to my sketchbooks I see with satisfaction how much of a workspace they are. While people have dogged me to make more finished drawings, and to reconsider my ‘style,’ and to think about what my preferred audience might respond to, I am pleased to see that I have wholeheartedly claimed these drawings as a working zone. Each life drawing session presents a new opportunity to investigate something new, and it’s not always a piece of anatomy. Recently I’ve been attentive to the way I make a mark, and how to train myself to make such marks. There are the soft lines that tentatively feel out the forms, and then the brazen, dark sweeps that claim them. I love to use a tiny butt of a pencil that fits inside the palm of my hand so I can ruthlessly stab the page with decisive marks, and every single week I practice this decision-making to varying degrees of success. And having uncovered some older drawings, I’m pleased to note that there is a greater elegance to my lines, but also that this elegance is laid down with such confidence and certainty. It is not only the weight of curves set off against each other that I am practicing week after week, but the very manner in which I lay them on the page. Nothing but sheer repetition and practice cements such things. As Sir Joshua Reynolds (1997: 281) writes of Michelangelo:

‘The great Artist … was distinguished even from his infancy for his indefatigable diligence; and this was continued through his whole life, till prevented by extreme old age. The poorest of men, as he observed himself, did not labour from necessity, more than he did from choice. Indeed, from all the circumstances related of his life, he appears not to have had the least conception that his art was to be acquired by any other means than by great labour.’

Ryan and I talk about the student’s perpetual search for surprise and freshness in their own work, the constant chopping and changing of media in an effort to chance upon something that they simply have a knack for, or that reveals something new—the apparently overriding fear of staleness. While this exploration is not without merit, it seems to prevent giving any one problem due attention. We have both remained faithful to the humble pencil, and reverent of its unlimited potential. While other media open up new thoughts, our ultimate goal is a deep and intimate understanding of and facility with our chosen medium. What we’ve learned via pencil can be transferred to many other media, but other media won’t substitute for the ability to set new tasks and doggedly pursue them. Actually, in stripping every problem back, in setting stiff parameters, we give ourselves a chance to isolate each task, to puzzle over it with clarity, to observe every minute shift in our approach and thinking. We have complete control over our learning and exploration, because we are so finely tuned into our chosen tool. We trust that accidents will never approach the rewards of systematic understanding.

The pencil lets us isolate, struggle with, and hopefully resolve distinct problems. But those problems are never really discrete, and are actually far more intricately bound with problems of colour, texture, light and atmosphere. But the life drawing studies demonstrate an important part of being an artist—the determination to pull apart and investigate—the indispensable precursor to being able to reconstruct, to compose an image, to integrate our knowledge into a wholly new and meaningful design.

Reynolds, Sir Joshua. 1997. Discourses on art. Ed. Robert R Wark. Yale: New Haven.

For a more regular drawing fix, have a look at my Tumblr! x