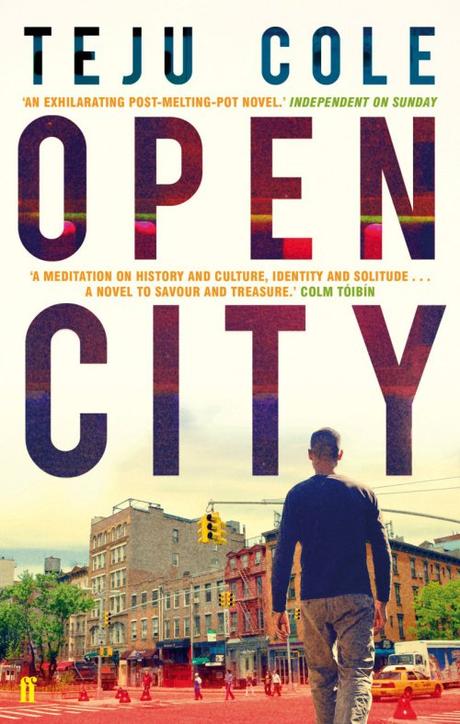

Open City, by Teju Cole

Identity and memory intermingle, both at the national level and the individual. Who we are is in part a creation of who we were, but our perception of who we were is itself a creation of who we think we are. Slippery stuff.

In the final year of his psychiatry fellowship Julius takes to walking the streets of his adopted home city, New York. His “aimless wandering” allows him to think, to observe. He is a flâneur of the New World, and for much of its length Open City is an account of his thoughts and encounters during his dérive.

By its end, it’s much harder to say exactly what Open City is. It’s too fluid and too subtle to be so easily pinned down.

I ENTERED THE PARK AT SEVENTY-SECOND STREET, AND BEGAN to walk south, on Sheep Meadow. The wind picked up, and water poured down into the sodden ground in fine, incessant needles, obscuring lindens, elms, and crab apples. The intensity of the rain blurred my sight, a phenomenon I had noticed before only with snowstorms, when a blizzard erased the most obvious signs of the times, leaving one unable to guess which century it was. The torrent had overlaid the park with a primeval feeling, as though a world-ending flood were coming on, and Manhattan looked just then like it must have in the 1920s or even, if one was far enough away from the taller buildings, much further in the past.

The cluster of taxis at Fifth Avenue and Central Park South broke the illusion. After I had walked another quarter hour, by then thoroughly drenched, I stood under the eaves of a building on Fifty-third Street. When I turned around, I saw that I was at the entryway of the American Folk Art Museum. Never having visited before, I went in.

Julius was born and raised in Nigeria to a Nigerian father and a German mother, then college-educated in the US. He is an intellectual, a lover of art and literature and particularly of classical music. If his brow were any higher he wouldn’t be able to walk through doors without crouching.

Over the course of the novel he walks around; looks at some paintings; visits an elderly professor who has become a friend; has an extended holiday in Belgium; gets mugged; meets some old companions from his childhood in Nigeria. On the whole it’s pretty uneventful stuff. The action here is internal.

Themes slowly emerge: recurring imagery of birds; musings on what constitutes freedom; the towering emptiness of the 9/11 Ground Zero site; questions of memory. Julius’ mind turns to art or to the problems facing his patients or the people and places that he sees. Through it all his voice is cool and dispassionate. Although his movement through the city is profoundly physical Julius remains always inside his own head.

The language of the book is, not to put too fine a point on it, beautiful.

The following day, returning to Sheep Meadow, on a circuitous route to a poetry reading at the Ninety-second Street Y, I noticed the masses of leaves dying off in bright colors, and heard the white-throated sparrows within them calling out and listening. It had rained earlier, and the fragmented, light-filled clouds worked off each other; maples and elms stood with their boughs still. Above a boxwood hedge, the swarm of hovering bees reminded me of certain Yoruba epithets for Olodumare, the supreme deity: he who turns blood into children, who sits in the sky like a cloud of bees.

As readers we are privy to Julius’ thoughts, to his interiority. Those around him of course are not, and one recurring element of the book is how other African immigrants repeatedly see him as a “brother”, a fellow African who has some kinship with them by virtue of shared origin and heritage. The connection they see is literally skin deep. In the US Julius is seen as a black man, an African, but he’s half German and in Nigeria was viewed at least by some as a rich white. What the Africans he meets see as a common link is to him mostly just an imposition by strangers of a false commonality. These African New Yorkers aren’t educated sophisticates like Julius – they’re taxi drivers and postal workers. Where they see bonds of race, Julius sees divisions of class.

For most of the book I accepted Julius’ view of himself at pretty much face value, and took the focus of the book to be his observations of the world around him. Perhaps that reflects my own nature as a slightly introspective intellectual type. Then however Julius goes to Brussels, ostensibly to find his maternal grandmother with whom he’s long since lost touch but really as an extended holiday. He takes about a month there, which with all due apologies to any Bruxellois who may read this is a hell of a long time to give a very quiet city.

In Brussels he naturally muses on the doubtful legacy of King Leopold II in the Congo. Belgium still has public statues to Leopold II and at home at least he doesn’t seem to be seen as one of the worst colonial monsters of the 19th Century. History has been kind to Leopold, largely forgetting the monstrous cruelty and slaughter he presided over.

Brussels today is the capital of Europe; Belgium is the European Union in microcosm with different nationalities co-existing under a shared but federalised polity. I’ve been there several times and it’s quite charming if perhaps a little dull for the casual visitor. It’s full of good restaurants and has bars with more choice of beer than I could drink in a lifetime. It’s easy to forget that many of its grand public buildings were financed by horror. History, like memory, is a matter of negotiable perspective.

It was a bronze bust of the poet Paul Claudel, set on a plinth on the side of the road like a shrine to Hermes. Claudel had served as French ambassador to Belgium in the 1930s, and later went on to fame as a writer of Catholic plays, and as a right-winger. His support for the collaborators and Marshal Pétain during the war earned him much scorn, but W. H. Auden, himself a leftist agnostic, spoke kindly of him. Auden had written: “Time will pardon Paul Claudel, pardons him for writing well.” And as I stood there in the whipping wind and rain, I wondered if indeed it was that simple, if time was so free with memory, so generous with pardons, that writing well could come to stand in the place of an ethical life.

While in Brussels Julius becomes briefly friends with a Morrocan immigrant named Farouq; a semi-radicalised intellectual who works in a phone shop and who has become highly politicised in the face of local prejudices. Julius and Farouq are both immigrants concerned with the world of ideas, both have left Africa to make new and better lives, but Julius has fared much better than Farouq and is as naturalised to his new home as Farouq is alienated from his. Farouq, driven to the margins of Belgium, is filled with fire and anger; Julius, who has found status and a comfortable income in the US, is uncommitted and resolutely apolitical.

Julius and Farouq’s conversations got me questioning quite where Julius stood. To be apolitical is a political choice, and Julius’ refusal to take a stance either with Farouq or to clearly break with him started to seem of a kind with his wider approach to life. He dislikes people who are too vocal about climate change, not because he disagrees with the science but from a distaste for “fashionable politics”. There can be such a thing as too much detachment. When he meets a postal worker who is also an amateur poet he agrees to go to a poets’ cafe with the man, but then makes “a mental note to avoid that particular post office in the future.” Most of us would do the same, but with Julius it starts to look like a pattern.

Julius is a perpetual outsider. In his role as flâneur he sees the city, but from a self-created distance. Where is the life in his life? He has his elderly friend, but where are the friends his own age? His girlfriend broke up with him, but where are the attempts to find someone new? He has his art, his music, but other than the rather sterile world of ideas who does he belong to?

Most of the people around me yesterday were middle-aged or old. I am used to it, but it never ceases to surprise me how easy it is to leave the hybridity of the city, and enter into all-white spaces, the homogeneity of which, as far as I can tell, causes no discomfort to the whites in them. The only thing odd, to some of them, is seeing me, young and black, in my seat or at the concession stand. At times, standing in line for the bathroom during intermission, I get looks that make me feel like Ota Benga, the Mbuti man who was put on display in the Monkey House at the Bronx Zoo in 1906. I weary of such thoughts, but I am habituated to them. But Mahler’s music is not white, or black, not old or young, and whether it is even specifically human, rather than in accord with more universal vibrations, is open to question.

Near the end of the book Julius encounters people he knew from his days in Nigeria, one of whom remembers him in a way that is completely at odds with his own ideas of self. It’s a profoundly jarring and uncomfortable moment, one that jolted me as a reader from the comfortable Julius-space I’d come to inhabit, just as Julius is jolted from his easy assumptions of who he is.

Julius quickly reasserts his sense of self and moves on, untroubled, just as Belgium today worries little about Leopold’s Free State and the lasting consequences for the Congo. As a reader however I was left uncertain as to quite what I had read, what the significance of the intentionally anti-climactic ending that followed was, and who the narrator was that I’d spent so long with. In a genuinely excellent interview with 3:AM Magazine, Cole says “there’s no such thing as a right to remain untroubled.” Part of Open City’s strength, quite beyond the sheer beauty of its prose, is how troubling it is.

I’ll end just by noting how much more I could have said but didn’t. I’ve only mentioned in passing the use of birds as a recurrent motif, and will have to leave analysis of that to others. There’s a great deal to be said about how Julius embodies a form of cosmopolitan diversity which is both internalised and very modern, and yet which very clearly belongs to an internationalised class of the highly educated and highly paid. There’s a great deal more to be said about the treatment of memory in the book. There’s a lot here. This is a book that merits close reading, and rereading. In the end I’m not sure there’s any higher compliment one can make to any book than that.

Other reviews

In terms of blogs fewer than I thought, though it may just be that I’m not finding them. Hungry Like the Woolf’s review is here, and is good on the birds and makes some interesting contrasts with Julian Barnes’ Sense of an Ending. Just William’s Luck’s review is here, and discusses among many other things the meaning of the title which I haven’t even touched upon. There’s a review at a political blog here which for me makes the mistake at one point of conflating Julius’ worldview with Cole’s, but which otherwise is highly perceptive and very strong on the book’s political elements. As ever, please alert me to any I’ve missed in the comments.

In addition, while I don’t normally link to newspaper reviews since I figure those are easy enough to find, it’s worth reading the tremendous comment by Bix2bop below the line at the Guardian’s review here. The review itself is fine and has some good points on negative space in the novel, but the comment is genuinely good and well worth reading.

Finally, here’s a quote from Teju Cole taken from the 3:AM interview I refer to above:

In my view, the novel is one of Europe’s greatest gifts to the world. America and Africa collaborated to give the world jazz. We’ll call it even.

That seems fair.

Filed under: Cole, Teju, New York Tagged: Teju Cole