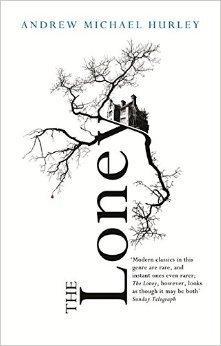

The Loney, by Andrew Michael Hurley

[I previously posted an incomplete version of this review – I accidentally deleted the majority of the text while making some fairly minor edits and didn’t realize until about a month later. The result didn’t make much sense. This is the review as it should have read.]

The Loney (and yes, that is the correct spelling) is a pretty much ideal winter read. I read it on kindle, where it comes rather pushily subtitled ‘The Book of the Year 2016’. I don’t know if I’d go quite that far, but it is intelligent, thoughtful and highly atmospheric and I can definitely see why it won a couple of first novel awards when it came out.

The Loney is a desolate piece of liminal landscape in the North West of England. The narrator’s family and church group used to go there on pilgrimage every year, back in the 1970s. Holidays were fewer back then and it’s clear that the trip was the highlight of their year.

In the first couple of pages or so we learn that the narrator’s brother, Hanny, is now a successful media friendly priest with a number of well-selling books to his name. It wasn’t always so. Back when they used to visit the Loney he suffered from a profound learning disability and each trip ended with a visit to a local shrine in the hope its waters would heal him.

In the present the narrator and his brother are semi-estranged, everyone talks to Hanny but him. When they were children it was very different:

He watched me as I undid the buttons for him and hung it on the peg on the back of the door. It weighed a ton with all the things he kept in the pockets to communicate with me. A rabbit’s tooth meant he was hungry. A jar of nails was one of his headaches. He apologised with a plastic dinosaur and put on a rubber gorilla mask when he was frightened. He used combinations of these things sometimes and although Mummer and Farther pretended they knew what it all meant, only I really understood him.

That discrepancy hangs over the book with its so very different present and past Hannys. The Loney doesn’t feel like a place where prayers will be answered, so what happened? The question lingered at the back of my mind as I read, creating a constant sense of foreboding. The framing device disappears for most of the novel leaving the reader aware that something will happen but as ignorant as those 1970s pilgrims of what it might be.

In previous years the church group had always visited with Father Wilfred, a severe priest marked by early poverty but with a clear devotion to his flock. For this trip he’s been replaced by the easy going Father McGill from Belfast. There’s a sense that they’re both in their ways good priests (this is actually a fairly priest-friendly novel), but those ways are very different.

The driving force for the group is the brothers’ mother. The narrator calls her “Mummer”, both giving a sense of regional dialect and hinting that she might not be entirely what she seems. She’s a deeply religious woman who wants everything just so. There’s a sense that under her strict demeanour she’s barely hanging on and that any deviation from how Father Wilfred did things could cause her to crumble.

In a lesser novel she and Father McGill would become enemies, sniping at each other in minor disagreements. Certainly it starts that way as she constantly corrects Father McGill telling him that Father Wilfred took grace this way, made himself available at these times, took confession in this fashion and so on. Father McGill is a better priest than she realises, sees her brittle fragility and patiently bends to accommodate her ideas of how things should be done while gently trying to tend to the needs of the others in the group also.

Behind this foreground of quiet despair and struggle lies the desolate Loney itself:

A sudden mist, a mumble of thunder over the sea, the wind scurrying along the beach with its crop of old bones and litter, was sometimes all it took to make you feel as though something was about to happen. Though quite what, I didn’t know. I often thought there was too much time there. That the place was sick with it. Haunted by it. Time didn’t leak away as it should. There was nowhere for it to go and no modernity to hurry it along. It collected as the black water did on the marshes and remained and stagnated in the same way.

There’s no sense this is a holy place. It’s been a few years since the last pilgrimage and on this visit the locals seem clannish and curiously unwelcoming. It soon becomes apparent that some are positively antagonistic, leaving a blasphemous effigy in the woods where the group will find it. Farther finds a walled-up room in the old house the group have always stayed in. It seems to have held children, long years past, and he finds in it an old artefact suggestive of past folk beliefs having survived longer than one might wish.

Tensions rise. Mummer can’t abide anything going amiss because if it does God may not heal Hanny. She means well, but it manifests as cruelty. Here Hanny doesn’t understand they’re supposed to be fasting in preparation for his cure:

Hanny started to lick his fingers, and Mummer gasped and grabbed him by the arm and marched him over to the back door. She opened it to the hiss of rain and pushed Hanny’s fingers further into his mouth until he emptied his stomach on the steps.

It’s little surprise that the narrator and Hanny get out whenever they can and wander the Loney’s windswept beach and the causeway which leads to another nearish (nowhere is that near) house. Usually there’s nobody there, but this year there’s a family staying and among them a heavily pregnant young teenage girl. It’s when they encounter her that things start to get really strange:

The injured gull had stopped shrieking and was hopping tentatively over to her outstretched hand. When it was close to her, it angled its head and nipped at the weed she was holding, its damaged wing open like a fan. It came again for another feed and stayed this time. The girl stroked its neck and touched its feathers. The bird regarded her for a moment and then lifted off silently, rising, joining the others turning in a wheel under the clouds.

It’s a miraculous healing, but there’s no sign of God. The Loney has a definite gothic atmosphere and has elements which seem plainly supernatural, though of an older order of faith than that which the Christians bring to the place. It’s not a neat tale and much is left unexplained (rightly so as explanations would have moved the book from a mood piece to fantasy). For the first half I just enjoyed it as an atmospheric spooky tale. The sort of thing that might have made a TV play back in the 1970s: The Stone Tapes; Children of the Stones; The Murrain; Quatermass; the play Baby from Nigel Kneale’s Beasts’ series. Folk horror.

The book remains throughout a highly effective folk horror tale (folk horror is rarely that scary, but often very disquieting). However, the supernatural elements do more than just spook the reader. They introduce proof.

The group worry that near the end of his life Father Wilfred lost his faith. Doubt seems to have corroded him. Doubt can of course be an enemy of faith, but it’s an enemy people of faith tend to know pretty well. The other great potential enemy of faith is proof, for with proof you have no need of faith. With the loss of Father Wilfred the group are hungry for proof, and when you’re that determined you can be sure you’ll find it:

After all, signs and wonders were everywhere.

Father Wilfred’s faith was a slab carved from the rock of doctrine and orthodoxy. Father McGill’s faith is softer, warmer, more malleable and so perhaps less vulnerable. The whole group could stand upon the solidity of Father Wilfred’s faith, but a single crack could destroy it. Father McGill’s faith is quieter and less inspiring, but perhaps a little more human. Father Wilfred died falling down church stairs – a literal fall to accompany his spiritual one. (This is a book that echoes with meaning, just as the Loney is a landscape that echoes with the absence of it.) Father McGill doesn’t try to carry the world alone. He just helps others carry their little bit of it.

Hurley leavens all this faith and desolation with a nice trace of humour, clearly understanding that 360+ pages of faith and gloom and doubt and barren landscapes would prove a bit indigestible. I particularly enjoyed the subtle competition between reigning queen of the group Mummer and the younger and more modern Miss Bunce who perhaps seeks to take her place:

Mummer was too engrossed in a contest with Miss Bunce as to who could be the most moved by the ceremony.

I really enjoyed the Loney. I’m not remotely religious myself, but faith in some ways is another word for meaning and we all struggle in our different ways to find that in the world. I thought Hurley pulled off the tensions of the book’s more intellectual explorations with the horror elements which are essential to avoid it becoming too dry.

This is a slow book and from the reviews it’s clearly a bit too slow for a fair number of people, but I found it deeply satisfying. Ideally you’d read it by a fireplace on a cold and windy night, glad as with all such stories that when it ends you can close the covers and head off to the comforts of a hot cup of tea and then a nice warm bed.

Other reviews

Caroline reviewed this at Beauty is a Sleeping Cat, here, which sparked a sleeping interest I already had in it. Tony reviewed it here at Tony’s Book World, and is absolutely right about that cake. Eric at The Lonesome Reader also reviewed it here and is very good on the symbolism (this is a book with a lot of symbolism).

Filed under: Horror Fiction, Hurley, Andrew Michael Tagged: Andrew Michael Hurley