Writing is a solitary task. We usually do it out of the limelight, in musky bedrooms, on flimsy typewriters—or not—for little or no pay. It’s tough stuff, and it tends to make us arrogant, competitive, and friendless.

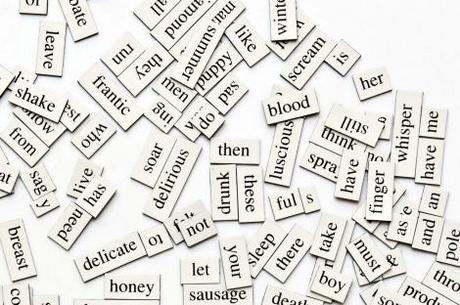

Sometimes we make ourselves feel better by taking a couple hits of big T—you know, Thesaurus.com, that smooth shit. Come on, it never hurt nobody! And, plus, everyone else is doing it, am I right? I promise that I won’t share my words, that I’ll keep it safe, that I’ll drift off and dream of Kubla Khan before anyone even knows….

There’s nothing wrong with consulting the thesaurus every so often for the mot juste. It’s a habit of the curious and scrupulous the world over. But sometimes people take the pursuit too far, pumping the internet for ever more obnoxious variants of words they already know. “Reiterate” turns into “reify,” and pretty soon we’re hosting the tweediest New England cocktail party with escargot instead of a backyard get-together with pigs in a blanket. It’s a brand of hooliganism—an addiction—and it brings out the worst in us.

Here’s a guide to help you spot when someone’s been a little too trigger-happy with a thesaurus. So you can judge them, of course.

1.) Too many two-dollar words in a sentence. It’s a truism, more or less, among thesaurus addicts: once you pop, you cannot stop. In the twisted brain of an addict, it’s really tempting to substitute big words for small words at every juncture. An addict will go way overboard instead of limiting him/herself to a few stealthly substitutions, as a dabbler might. Therefore, you get sentences like this—

“With the last gasp of Romanticism, the quelling of its florid uprising against the vapid formalism of one strain of the Enlightenment, the dimming of its yearning for the imagined grandeur of the archaic, and the dashing of its too sanguine hopes for a revitalized, fulfilled humanity, the horror of its more lasting, more Gothic legacy has settled in, distributed and diffused enough, to be sure, that lugubriousness is recognizable only as languor, or as a certain sardonic laconicism disguising itself in a new sanctification of the destructive instincts, a new genius for displacing cultural reifications in the interminable shell game of the analysis of the human psyche, where nothing remains sacred.”1

when this would suffice:

Romanticism gave way to Gothic literature, and it was great. But also sad.

Lesson: never underestimate the stamina of an addict. Their ability to perplex is directly linked to their desire to seem smart.

2.) Faulty prepositional usage, lack of parallelism, etc. Sadly, the breezy thesaurus abuser does not know or care about the intricacies of proper English language usage. For him or her, the important part of writing is to cover every sentence with a glossy sheen so that it looks good and sounds smart. Therefore, the abuser will sometimes make grammatical mistakes, usually having to do with prepositions, when plugging and chugging all willy-nilly. Example:

Little Timmy abjured to the charge of stealing Stewart’s Nutter Butters.

Abjure is a good word. It means to deny or renounce under oath. But the abuser failed to note that abjure isn’t a prepositional verb, making “abjure to” abjectly incorrect. The abuser, most likely suffering from indigestion after a fruitless trip to Wingstop, probably started off using “objected to,” then got a little sick and changed it to “abjure” without bothering to check if “to” still belonged.

Lesson: the heart of an abuser is frail (with indigestion), and the mind is lazy.

3.) A preference for the abstract instead of the concrete. We’ve learned by now that the aim of the addict is to perplex the shit out of you and still appear smart. How does s/he accomplish this? An over-reliance on abstract words is usually a good indicator of thesaurus theft. That’s because abstract words signify a wider range of possible meanings than concrete words, and addicts want to happen upon meaning more than they want to specify it.

Example: T.C. Boyle likes to describe everything in nature as “preternatural.” The stream purred preternaturally. The wind howled preternaturally. Her boobs were preternatural. You know, stuff like that. I’m not accusing Mr. Boyle of anything aside from lame descriptions of nature, but I will say this: it’s a lot easier to write “The stream purred preternaturally” than it is to write “The reef of rock was about two feet under the water, so the whole river rose into one wave, shook itself into spray, then fell back on itself and turned blue.”2

Lesson: say what you think, not think what you say. Also, avoid unnecessary descriptions of nature.

* * *

Let me come clean. I am a recovering addict. I have the chips to prove it. Once, not too long ago, I piled words upon words in the sleaziest fashion, without regard for my own dignity or the suffering of others. It was wretched; I definitely used the words “phthisis” and “protuberance” a little too indiscriminately. For that I am sorry. I have emerged from despairing times, however, with a few tips:

- Read your writing out loud. If your work sounds like the garbled love-child of a Vatican treaty and a Joanna Newsom song, change it. The best writing heightens the directness and cadence of natural speech with only a tiny bit of flair.

- Read something every day. The more you read, the better you will write.

- Don’t worry about sounding smart. The people who worry about sounding smart tend to look dumb.

- Omit needless words. If you don’t know exactly why you used a word, omit it. In the symphony of your writing, nary a note should ring untrue.

_____________

1. Penned by Stephen T. Tyman, in “Ricoeur and the Problem of Evil.” Go get ‘em, champ.

2. Excerpt from “A River Runs Through It,” by Norman Maclean.