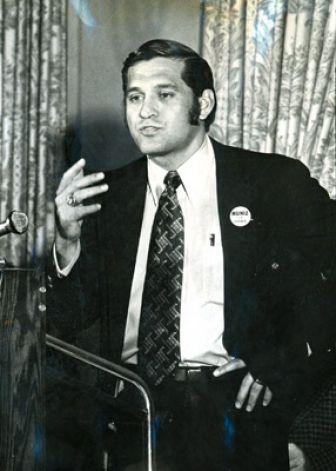

Ramsey Muniz runs for Texas governor in 1970

By Alan Bean

Ramsey (Ramiro) Muniz is a man of seventy who hobbles on a bad hip, but his spirit grows stronger with each passing day. Ramsey has now spent two full decades in federal prisons (including three years in solitary confinement) for participating in an alleged narcotics conspiracy. Supporters feel that a septuagenarian with a broken body and a vibrant heart is a sterling candidate for a presidential commutation. I agree. But first we must face a troubling question. Somebody entered into a conspiracy with a Mexican drug lord, but was it Ramsey Muniz or was it the federal government?

Eager for a big media splash and an easy conviction, the Houston office of the DEA treated their counterparts in Dallas to a series of carefully staged events while intentionally obscuring the truth. Those who testified at trial had no idea what was going on; those who knew the truth did not testify. The DEA got a big media win, a drug lord got a plane ticket back to Mexico, and Ramsey Muniz got a life sentence.

In the early days of March in 1994, Denacio Medina flew from Mexico City to Houston, Texas. A week later, Ramsey Muniz was arrested in Dallas. Medina had a legal problem too big to be handled over the phone. Two of his brothers were in federal prisons facing narcotics conspiracy charges, one in El Paso, the other in San Diego. Neither brother stood a chance at trial, but Medina wanted to minimize the legal damage. More significantly, a new NAFTA-related law made it possible to transfer Mexican nationals convicted in the United States to Mexican prisons where, Medina hoped, they would be more likely to secure an early release (there is no parole in the American federal system).

Medina’s family was awash in drug money, and he intended to hire the best defense attorney on the market. Ramsey Muniz enters the story because he had a working relationship with Dick DeGuerin, a Texas attorney with a reputation for working miracles for well-heeled clients.

We don’t know how or why, but shortly after arriving in Houston, Denacio Medina was picked up by DEA agents and subjected to a thorough debriefing. Asked why he was in the United States, Medina likely told the truth: he had come to hire an attorney and his pending appointment with Ramsey Muniz was proof of that fact.

When the feds learned that Medina was talking to Ramsey Muniz their suspicions deepened. In the eyes of most Texas Latinos, Muniz was remembered as the Baylor educated attorney who ran for Texas governor on the La Raza Unida ticket back in the 1970s. But Muniz had gone to prison for five years in 1977 when one of his clients found himself in the same position Denacio Medina was now in. Muniz admitted he had attended meetings his clients’ illegal activities were discussed. He thought he was covered by attorney-client privilege—he was wrong.

You may be asking why a man with two brothers facing long stretches in the federal prison system would cross the border to do a drug deal that could easily have been transacted by his family’s Texas affiliates. None of that mattered to the DEA. They had a chance to make a high-profile drug bust involving a Latino icon, and they intended to make the most of the opportunity. As Upton Sinclair has famously said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his job depends on not understanding it.”

There was only one way Medina could return to Mexico as a free man—he had to confirm the DEA’s darkest suspicions, and that meant making it appear that he and Muniz really were planning a drug deal. Medina may have procured the narcotics through his family’s Texas connections, but it is more likely that the DEA, eager to ensure Medina’s cooperation, supplied the swag out of their own stash. This would have been standard operating procedure.

Muniz was working as a paralegal at the time with a law firm in Brownsville, Texas and was scheduled to spend several days visiting with potential clients in Dallas, so the scam had to unfold in North Texas. The goal was to tie Muniz to a vehicle loaded with drugs. If that didn’t work out, Medina was hoping the feds would be satisfied with finding drugs in a car that could be traced to Muniz.

The day after being “debriefed” by DEA officers in Houston, Medina rented a white Mercury Topaz using a credit card belonging to Juan Gonzales, the man who was scheduled to drive Muniz to Dallas in a few days. According to the trial transcript, Medina told Gonzales that he needed to rent a car but lacked a Texas driver’s license. Gonzales had a license but no money, and his Sears credit card was $300 in arrears. Medina offered to pay off the Sears card if Gonzales would use it to rent a car for two days. This amounted to $250 in free money and the simple laborer from the Rio Grande Valley readily agreed.

Next, the Houston DEA informed Medina that a confidential informant using the fake Danny Hernandez had just booked into the Class Inn, a flea bag motel in Fort Worth. Hernandez had no identification because, as he told the man at the desk, his wallet had just been stolen. At low end motels nobody asks questions to paying customers. By sharing a room with Hernandez, Medina had a safe place to leave the rented Mercury Topaz without leaving a paper trail.

We know that Medina was staying at the Classic Inn on March 9th, the day after Muniz and Gonzales checked into the Ramada Inn in a North Dallas suburb. Phone logs show that Ramsey Muniz received a call from the Fort Worth motel that day. Since Medina flew from Houston to Dallas the evening of March 10th, we must conclude that he drove the drug-laden car to Fort Worth, then flew back to Houston where he boarded a plane back to Dallas. If Medina and Muniz were true conspirators none of this would have been necessary; but if the plan was to simulate a drug deal, a few weird gyrations had to be factored into the equation.

Legal records make it clear that agents in Houston staged the Muniz bust while their counterparts in Dallas were intentionally kept in the dark. After delivering the “load car” into the safe keeping of the mysterious Mr. Hernandez in Fort Worth, Medina returned to Houston so agents with the Dallas DEA could observe Ramsey Muniz picking him up at the Dallas airport.

We are dealing with a classic bait-and-switch scam. Dallas agents who were carefully shielded from the salient facts of the case testified at trial. The jury never learned about the DEA agents in Houston who orchestrated Medina’s every move.

Ramsey Muniz was attending the 75th birthday party of a family friend when Medina called asking to be picked up at Love Field. Muniz didn’t drive and Juan Gonzales was returning from an emergency trip to the Rio Grande Valley, but a young man at the birthday party agreed to drive him to Love Field. Medina told Muniz that his shuttle diplomacy between Dallas and Houston was designed to line up the $250,000 the Mexican businessman had agreed to pay Dick DeGuerin.

Moments before this rendezvous at the Dallas airport took place; the Houston DEA called up their counterparts in Dallas and asked them to check out two Latino males fitting the description of Muniz and Medina. Dallas agents followed Muniz and Medina for a couple of miles before breaking off surveillance at the request of the Houston office. Later that evening, Houston instructed Kimberley Elliott, head of the Dallas team assigned to the case, to drive to the Ramada Inn.

In her incident reports, and at pre-trial hearings, Agent Elliott claimed she drove to the Ramada Inn because she had received a call from Ramada employees who were concerned about a couple of suspicious men of “Latin” appearance who were using the lobby phone. Elliott abandoned this theory at trial, admitting that she drove to the motel at the insistence of the Houston DEA. Motel employees had not been the least bit suspicious of Muniz, it turned out and no one at the Ramada Inn had ever called the DEA. Elliott’s doctored reports and perjured testimony at pre-trial hearings were designed to obscure the involvement of the Houston Office from the judge, defense counsel and the jury.

If the Dallas DEA agents had maintained their surveillance, they would have seen Muniz and his companions return to the birthday party where Ramsey was scheduled to make a brief speech. Meanwhile, Medina moved from guest to guest offering handsome remuneration to anyone who could drive him to Fort Worth. A Fed Ex driver named Danny Gallardo testified at trial that he took Medina’s offer and was directed to the Classic Inn. Medina disappeared for a moment, then climbed back in the car and told Gallardo that his car wasn’t at the motel. Gallardo was instructed to drive to the Ramada Inn in North Dallas.

According to trial testimony, Muniz was walking across the Ramada parking lot carrying a bag of groceries when he was approached by Denacio Medina. The two men chatted briefly before a stranger standing in the shadows called Medina’s name. Medina promised to be back first thing in the morning then climbed into the stranger’s vehicle.

True to his word, Medina was back at the Ramada Inn the next morning. Juan Gonzales had returned from his emergency trip to the Rio Grande Valley just in time to join Muniz and Medina for breakfast. As the two men chatted over their bacon and eggs, Medina said he would be returning to Houston that morning and asked for a ride to Love Field. A DEA agent who was monitoring this conversation claims he heard Medina say something about a deal scheduled for 10:00. The agent learned nothing about the nature of this transaction or if the projected time was morning or evening. But the Houston DEA was insisting that all three men at the restaurant were big time drug dealers, so the agent concluded that Medina was talking about drugs.

The three men drove to Love Field where Medina entered the terminal and was taken into temporary custody by a DEA agent. As Gonzales made his way back to the interstate he made two surprising revelations. Muniz learned that Medina’s rental car needed to be moved from the Ramada Inn a mile south to the La Quinta. Gonzales reported that he had decided to remain in Dallas to look for work and would be staying at the La Quinta.

Since Juan Gonzales failed to testify at trial it is impossible to know with certainty what transpired between Medina and the hapless Mr. Gonzales. At some point, Medina asked Gonzales to return the rental car for him. Gonzales likely complained that the car was now five days overdue. Medina may have promised to pay for a room at the La Quinta if Gonzales agreed to return the car. Medina and Gonzales clearly worked out a deal of some kind, but Muniz was left completely in the dark. Since Gonzales ended up doing fifteen years for his part in the alleged conspiracy, it is unlikely that he knew Medina was working with the feds.

Ramsey didn’t mind losing his driver. His wife, Irma, had been asking him to fly home and phone logs show Muniz had been discussing travel plans with Southwest. He had one more legal consultation scheduled for noon after which he was free to leave Dallas.

But moving Medina’s car was a problem. Muniz had allowed his license to expire because he didn’t drive. Five years in prison had left him a bit paranoid about car ownership, and he found he got more work done if someone else was driving. But the drive would only take a couple of minutes so there was little danger of getting stopped. Muniz climbed behind the wheel of the Topaz and followed Gonzales to the La Quinta. Moments after parking the car, he was approached and questioned by Dallas DEA agents, $800,000 of powdered cocaine was discovered in the trunk of the Topaz, and Denacio Medina was on a plane back to Mexico.

The jury never learned that every move Denacio Medina made was scripted by the Houston DEA. Dick DeGuerin, Ramsey’s defense attorney, wasn’t told that Medina had been “negotiating” with the feds until moments before he delivered his closing remarks. DeGuerin didn’t unearth Medina’s relationship to Hernandez until midway through the trial and, because he wasn’t told that Medina was working with the Houston DEA, DeGuerin failed to grasp the significance of the Hernandez-Medina connection.

The jury was exposed to a simple narrative limited to the “evidence” witnessed by the Dallas DEA. Would the jury have voted to convict if all the facts had been on the table? Would a case this flimsy even go to trial? The Houston office of the DEA had good reason to keep its fingerprints off this case.

After twenty years in prison, the seventy-year old Ramsey Muniz should be released from prison on humanitarian grounds. But the man who ran for governor in 1970 on the La Raza Unida ticket has maintained his innocence from the moment the trunk of the Mercury Topaz was lifted. The record shows that Denacio Medina set up Ramsey Muniz to save his own skin. The Houston DEA offered assistance and advice at every stage of the operation and likely supplied the drugs found in the load car. This nasty business was completely legal and utterly immoral. If President Barack Obama ever takes a close look at the facts of this case he will issue an immediate commutation. It is our job to ensure this tragedy receives the attention it deserves.