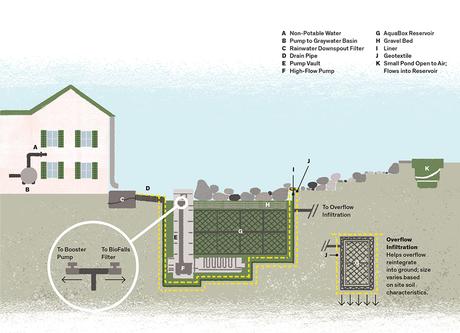

RainXchange helps manage storm-water runoff and has provided safe drinking water for many communities around the world. Beneath a scenic, seemingly passive water feature is a revolutionary hidden system that stores and filters rainwater for reuse while providing a habitat for wildlife.

A Non-Potable Water

B Pump to Graywater Basin

C Rainwater Downspout Filter

D Drain Pipe

E Pump Vault

F High-Flow Pump

G AquaBox Reservoir

H Gravel Bed

I Liner

J Geotextile

K Small Pond Open to Air; Flows into Reservoir

Image courtesy of Maggie Li.Known as “the Scientist” at the design-build firm Aquascape, in St. Charles, Illinois, Ed Beaulieu has dedicated his practice to implementing and restoring freshwater ecosystems. Beaulieu, a member of the Nat Geo Wild channel’s Pond Stars team, makes rainwater harvesting more efficient through innovations such as his RainXchange filtration and collection system, versions of which he has implemented in Ghana, Uganda, and Colombia. Beaulieu shares his expertise to highlight new conservation initiatives and meaningful changes we can all make.

We’ve had record snowfall in the Northeast and a historic drought in the West. How can we be smarter about water?

Too much water and not enough are both serious problems. Rainwater capture isn’t just about finding an alternate water source, it’s slowing storm-water runoff. The entire water system of Toledo, Ohio, got shut down last summer because of cyanobacteria in Lake Erie. The red tides of Florida and California are directly related to runoff.

At the same time, we treat this resource that’s falling on our properties as a waste product. The average roof in the United States generates about 1,800 gallons of water in a one-inch rain. That’s a heck of a lot. Even if you have a bad precipitation year in California or Arizona, you still might have 10 to 12 inches of rain. That’s 18,000 gallons or more.

How can we harvest that?

I’ve created everything from small backyard rainwater-capture systems to 100,000-gallon reservoirs under parking lots. We can put together a plan to capture enough water to irrigate landscape beds and for outdoor water usage.

Roof water is about as clean a source as you’re going to find, but the minimum I’ll do is aerate it to keep it in good condition. For water that hits the ground, we have to manage things like pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides by filtering it in different ways: a mechanical filter to remove big sediments; a biological filter, which has bacteria and enzymes to break down and biologically consume a lot of those large compounds; and phytoremediation, which uses plants to treat pollutants.

I have a simple philosophy that I call H2O, or Homes 2 Oceans. It’s the idea of creating a connection between humans and the environment through the use of aquatic ecosystems. A backyard water feature is not only good for local wildlife while protecting aquatic resources, it creates a greater awareness of our environment, which in the face of rapid expansion and growth is critical for the health of the oceans and the entire planet. Even though we may not see it or understand it, everything in our world is interconnected, so small changes at our homes, even in the Midwest, will impact the oceans.

Any urban water-management initiatives that we should know about?

Philadelphia has been designating funds for every new project that goes in the ground. A portion of that will go toward green infrastructure: installing permeable pavement, rain gardens, and rainwater-catchment systems. Chicago has a Green Alley program to create an underground storage system and put the water back into the aquifers. And Santa Fe, New Mexico, is mandating rainwater-catchment systems for new developments. The biggest challenge is that the technology is so new. But progressively minded communities are saying, “Let’s see how these philosophies work in a real-world situation.”

What can the average person do?

If everyone were to dedicate half of their property to native plantings, rainwater capture, and sustainable water features, we’d create the largest national park in the world. I’m talking about the simple stuff: the birds, the bees, the butterflies, the things that make our world tick. We take it for granted that honeybees and other insects will pollinate our crops, but they’ve taken a big hit because their habitat has changed. These backyard oases are important habitats, with food, water and shelter. It’s a management philosophy in practice: Let the water go back into the ground, try to keep it out of the storm drains—capture it first, slow it down. Start somewhere. Just do something.

What’s the most basic rainwater harvesting system out there, and how much does a typical system cost?

The most basic rainwater-capture system is as simple as placing an empty bucket under your downspout to capture a few gallons of rainwater. If you have an old bucket, there’s no cost other than taking the time to do it. Use the water on indoor or outdoor plants, and your plants will love you! Rainwater is a great source of water that’s free of chlorine and other compounds that actually inhibit plant growth.

Can people create their own systems, or do they need help from a professional?

You can definitely create your own system to intercept water from a downspout and reroute it into a watertight container so it can be reused or rerouted into an appropriate location on the property to allow the excess water to percolate back into the soil and replenish the groundwater.

Involving a local professional is a safe way to ensure that the system will function properly. Water can be a challenge, and most communities have a well-designed storm-water conveyance system for a reason. Flooding and excess water can create serious problems to property and homes, so any modifications should be well thought out. The most important part of a rainwater-capture system is to intercept a certain percentage of the rainwater and then allow the rest of it to continue on its original path into the existing storm-water system.

How important is aerating the water stored in rain barrels?

An aeration system is beneficial if the captured water is going to sit for extended periods of time without being used. The stored water will become anaerobic quickly, which can foul the water. Rainwater that’s stored for more than a few weeks should be aerated to increase the water quality.

Adding an aeration system is very simple. A small pond bubbler or an aerator for a large aquarium will work effectively. Pond supply stores, garden centers, and aquarium shops all carry a variety of bubblers and aerators. Installation is very simple: You place the aeration diffuser on the bottom of the container and connect the diffuser to the compressor using the tubing supplied with the unit, plug the compressor into a ground-fault circuit interrupter outlet, and your rainwater will last for months.

How can homeowners learn more about available options for capturing rainwater?

There are experts and educated professionals in every community. Once you make contact, you’ll find an entire sub-community of people and information on the subject. There are water-conservation specialists and rain-barrel and rain-garden programs. Local connections are the best source of information, because they can provide insight into the local environmental and water issues facing the community.

Is there a certification program for professionals who specialize in rainwater reclamation and capture?

There are certifications available to professionals. Magazines like Land and Water and Stormwater are great resources for professionals, as is your local soil and water conservation district.

How can we learn more about which plantings are native to our particular environment?

You can do your own research online, but there’s a lot of information to sort through. A local nursery or garden center will know what grows best in your specific region. Local botanical gardens, environmental centers, and nature preserves are great resources as well. They have staff familiar with native vegetation and conservation initiatives like water management.