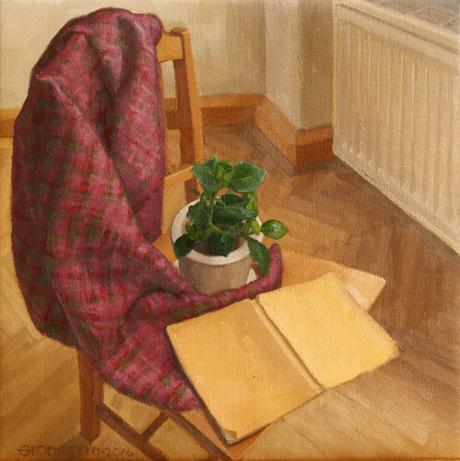

Russian plant © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

Language, woven of conventions, adapts and evolves, but Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s account of its progression takes a delightfully unexpected path. Language, he (2009: 294) declares, was born of the passions: ‘Neither hunger nor thirst, but love, hatred, pity, anger wrested the first voices from them.’ Physical needs are easily signalled; but the complexities of expressing gently nuanced emotions—of swelling love overlaid with brittle melancholy; of restless expectation shaded with pleasant hope—demand a more developed mode of intimation. The first words to escape our trembling lips must thus have been effusive outpourings of raw poetry, only to be subdued and ordered much later by reason. Language’s intellectual ripening carried it further and further from its first poetic utterances: ‘In proportion as language was perfected, melody imperceptibly lost its ancient energy by imposing new rules upon itself’ (Rousseau 2009: 329).

But painting may be spared this ruthless pruning. Painting, as language, has never been reigned in to express concepts with logical precision. It rather remains an unruly address to the eyes that harmonises with the chaotic cadences of our hearts. We are moved because we discover our passions and imitations of the objects of our passions candidly reflected in paint—it is in this empathetic manner that paintings speak with us. And ‘one speaks to the eyes much more effectively than to the ears,’ Rousseau assures us (2009: 291).

Rousseau reserves particularly high praise for drawing. Good painting touches us, certainly; but we ought not overestimate the role of colour in this. Colours, argues Rousseau (2009: 319), operate at a simple sensory level. They strike us immediately, they catch our attention, they please our eyes, but colours alone cannot move us. ‘It is the design, it is the imitation, that endows these colours with life and soul, it is the passions which they express that succeed in moving our own, it is the objects which they represent that succeed in affecting us’ (Rousseau 2009: 319). Colourless drawings retain their expressive force; but colours without contours melt into pure sensory pleasantness (Rousseau 2009: 319).

Rousseau privileges drawing with a more fundamental position than words, much nearer to the earth and to our volatile passions. Love, that consuming passion, ‘has livelier ways of expressing itself’ than with the very words it summoned into existence, however poetic those words may be (Rousseau 2009: 290). Love is fabled to be the impulse that compelled the first drawing. Rousseau (2009: 290) swoons with evident delight: ‘What things she who traced the shadow of her lover with so much pleasure told him! What sounds could she have used to convey this movement of a stick?’ And so we clutch our sticks, the ‘Griffel’ of Max Klinger’s (1985: 21) ‘Griffelkunst,’ with renewed vigour, finding ourselves closer to the poetic expressiveness we crave. ‘Writing, which seems as if it should fix language,’ systematically changes language—categorically domesticating it, demanding ever more precise adaptations, shedding its poetic origins. Drawing, by contrast, abandons the pursuit of precision in order to move us in more complex and thus deeper ways (Rousseau 2009: 300).

It is this resolute devotion to the passions that lends drawing its eloquence. Our visual language, built of rhythmic lines and deliberately constructed compositions, possesses all the tools of charming and winning over our audience: we have not the means to persuade, but to stir. We rely not on arguments, but on poetry, and poetry and eloquence, says Rousseau (2009: 318), have the same origin. While we search out logical colour series, and look for technical solutions that make clear statements about light, about form, about perspective, our technical grammar is subservient to our elusive poetic aims. We ought not forget our advantage, for even words derive their eloquence from the visual, as Rousseau (2009: 291) reminds us; they move us most when infused with imagery and colour through metaphor.

Drawing—design—with unlimited poetic potential, saves the visual language of painting from too strict a grammar. Because though there are means of drawing more accurately, more naturalistically, more literally, the best drawings may be judged to harness the grammatical concerns of truth and precision for more expressive purposes, to elevate something poetic in the subject. An able draughtsman pursues accuracy; a good draughtsman tells seductive lies with his eloquent stick. His impassioned retellings are more captivating than the truth; the visual grammar he works within does not ever refine itself towards rational precision. Good drawing orders a painting according to another kind of logic. It makes the painting a painting, not a mirror image, not a soup of sensations.

Our language, as painters, is rooted in the grammar of design. We must search out the visual patterns, impose hierarchies, intentionally structure our images, and chase endlessly after the stirring undulations of our lines, for herein lies their emotive strength. Used forcefully, we may speak with an eloquence that moves our viewers more deeply than any string of words. Words have evolved as a tool of persuasion, and ‘by cultivating the art of convincing, that of moving the emotions was lost’ (Rousseau 2009: 329). Drawing, and through it, painting, has not suffered as a language at the hand of progress. Its conventions, though they shift and change, tie it ever to its emotional source.

Klinger, Max. 1985 [1885]. Malerei und Zeichnung. Leipzig: Philipp Reclam.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 2009 [1781]. Essay on the Origin of Languages and Writings Related to Music. Edited by John T. Scott. Trans. from the French edition. Hanover N.H.: Dartmouth.