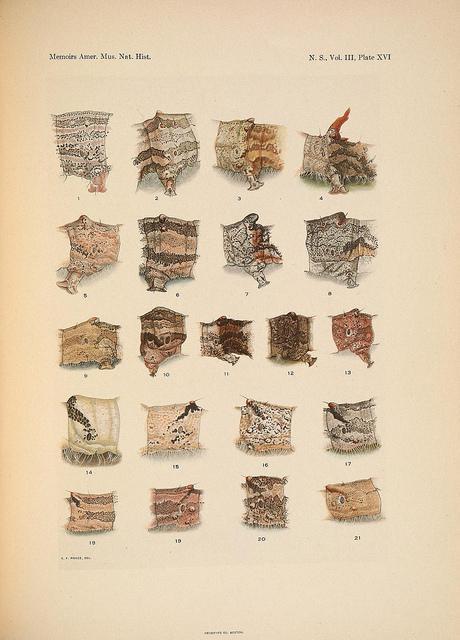

North American Species of the Genus Catocala, New York, 1918

{A few days ago I looked through an optical tube of marvelous clarity, and was astonished by what I saw. It was made with great skill and craft by two Germans who brought it to my house and presented it to me. Since it was made for the observation of very small things, I decided to call it a microscope, by analogy with the telescope. I examines a louse, that dirty little animal, and not infrequent companion of man, and saw not only its mouth, but its eyes, beard and two little horns on its forehead. I examined its three very long and articulated feet on either side of its body; each had two curved claws, one long and one short, which took the place of the thumb. [. . .] How much care and perfect diligence Nature devoted to this tiny digit, and to every similar detail of these most abject little animals. —Johann Faber, Thesaurus, 1624}

‹12 April. Always loved bees and butterflies. Always wished I could really devote more of my time to never-ending issues of classifications, in the way fossils and knotty twigs of a tree could absorb the lives of other people—the undulating growth lines, grains, metallic fibers, and twinkling pyritic elements. And I always imagined football itself turning into these woody shapes, and players like Rooney, Del Piero, or Van Persie embodying the inexhaustible varieties of woodiness, to the point that it becomes impossible to escape the problem of overlapping and borderline forms.

There could hardly have been, in truth, a more persistent attempt than in the sporting life to record the minutiae of difference (as historians later said Galileo and the Linceans claimed) and to use drawings to illustrate the texture and surface accidents of the samples one observes on the field. By now, the work of the soccer assayer appears to have received its fullest statement. It is time, perhaps, to access a whole new vocabulary to describe the game: how a striker is barky, a winger knotty and full of whorls, how the markings of a defense are rootlike, encrusted, tuberous, turbinate, or spongy—to say nothing of how attacking movements can be said to be convoluted, anfractuous, ferruginous, or sulfurous.

Measurements are always given, thanks to modern representation, and the same footballing specimen is often shown from several different angles. Yet, beyond this nomenclatural drive, one feels the need to resolve matters of classification by first addressing deeper issues of faith, passion, and reproduction. Some strikers are so right-footed or left-footed to make problematic their description as gastropods and bivalves; others raise the definitional problem of animal versus mineral. It is nature against nature, and firsthand observation of the grid of things: a whole section of petrifying juices and nocturnal liquefaction under the stadium lights.

‹13 April. Returned, at last, to one of my most cherished projects. The bees and the butterflies are resting from the intense labors of the previous few days. It is a pleasant caesura from the grand cosmological controversies and the urgent matters of Copernicanism which had beset us for so long. Had a conversation about football that took a rather more aesthetic turn than usual, a turn that would be of some consequence as I write this note. Also looked at a few rudimentary etchings in a Parisian manuscript that belonged to a member of the Lincean Academy—drafts that went to extraordinary lengths to emphasize, both verbally and visually, the amphibian, ambiguous nature of things. One could almost sense the pride, at once sumptuous and abstract, in the author’s commitment to writing field notes.

If the “jokes of nature” were a central focus of the Linceans’ researches (they apparently took seriously all instances of nature going awry), the draftsman—whoever he or she may be in the current version as a sports writer—does his or her best when a verbal description is matches in pictorial terms. The problem of sorting out the best soccer order, in other words, lay in the draftsman’s own hands.

Take the graphic piece of evidence numbered 34A in my paper museum, which illustrates the strange work of soccer twins such as Emanuele and Antonio Filippini at Brescia or Ronald and Frank de Boer at Ajax.

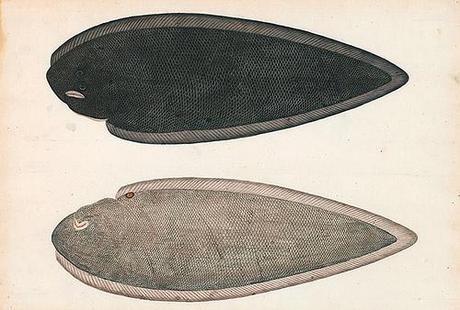

Bengal River Fish, ca. 1804

It is executed with great refinement and coloristic subtlety. The painting belongs to the so-called Calcutta school and is from the collection of Marquis Wellesley, governor-general of India from 1798 until 1805. What interests me here is primarily that the twin images of each side are placed by one another, the upper image in a dark gray tone and the lower one in a paler shade of the same color. What if the markings of this Bengal fish—its mouth and eyes, the mottled, scaly surface of its body—could parallel the perplexing nature of these football players? Are these markings the product of art of nature? One way of resolving such a problem would be by a supplementary picture, not by a text. Even tactical issues can be made a consequence of the fineness of the drawing. If the drawing were weaker, it would be easier to dismiss.

Drawings are not only fitted to the representation of footballing matters, they could actually serve as proof (and not just as an indicator of the monstrous) of what is genuinely aberrational in the game. With this in mind, I offer to my readers a first set of illustrations, hoping to drive them through skepticism and puzzlement to inexplicable resemblances and to show how the most troublesome cases in soccer can be described as a fossilized nut or a dried mushroom. ♦

TEN PLATES FROM THE SERIE A →

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Previously in this series: Milan’s Pitch-Pine Cone Shapes.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________