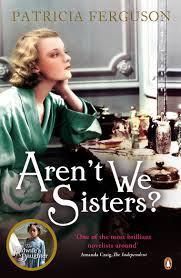

I am not the first person to write with a sigh in her voice about the way that ‘women’s fiction’ still seems to have a taint of inferiority about it. And it’s hard to pin down what separates one sort of fiction, presumably read more by women than men, from another. Helen Walsh’s The Lemon Grove, for instance, a steamy tale of lust set on Mallorca during a family holiday from hell, garnered plenty of reviews from the main newspapers. I certainly enjoyed it but can’t imagine Mr Litlove reading it (I am very sorry to say there are certain parts of it he would enthusiastically read, but not the novel in its entirety). Whereas the splendid Aren’t We Sisters? has a review from mumsnet topping its search engine enquiry and a steady silence emanating from the dailies. Is it because the focus of the novel is reproduction, rather than sex? Remove the fun component and inevitably one must leave all that business with bowls and hot water and screaming to women alone?

I am not the first person to write with a sigh in her voice about the way that ‘women’s fiction’ still seems to have a taint of inferiority about it. And it’s hard to pin down what separates one sort of fiction, presumably read more by women than men, from another. Helen Walsh’s The Lemon Grove, for instance, a steamy tale of lust set on Mallorca during a family holiday from hell, garnered plenty of reviews from the main newspapers. I certainly enjoyed it but can’t imagine Mr Litlove reading it (I am very sorry to say there are certain parts of it he would enthusiastically read, but not the novel in its entirety). Whereas the splendid Aren’t We Sisters? has a review from mumsnet topping its search engine enquiry and a steady silence emanating from the dailies. Is it because the focus of the novel is reproduction, rather than sex? Remove the fun component and inevitably one must leave all that business with bowls and hot water and screaming to women alone?

Well, whilst Aren’t We Sisters? combines a number of perspectives on childbirth into a clever and enjoyable book, it is happily less interested in the gore than in attitudes of society and the amazing lengths women had to go to, to hang onto their veneers of respectability. Set in the 1930s it vividly depicts a world in which women’s bodies were policed with ferocity but rarely protected from harm.

Nurse Lettie Quick has taken up residence in the Cornish town of Silkhampton for reasons she is keeping to herself. Even her official business is too shocking to be openly discussed, for Lettie is a disciple of Marie Stokes and has arrived in town partly to save the local women from more babies than they can afford to feed, and the dangerous methods currently available to prevent them. But this isn’t all she is here to do. Lettie, who knows what it is to scramble out of poverty and has her sights set on the finer things in life, is open to more innovative ways of earning her keep. Several miles away, in a deserted area of the county, a young, pregnant woman has come to have her baby in hiding, and Lettie, if she can overcome her terrors, is here to help.

Norah Thornby has recently lost her mother and gained the debts and expensive maintenance of her large family home. What she unfortunately has not lost is her mother’s opinionated voice, reaching her from beyond the grave. ‘Such a stalwart thumper of a girl!’ her mother used to sigh over her, and Norah is aware she has very little going for her, shy and unskilled and hopeless as she is. Only her passion for the movies keeps her spirits up, and her belief that hidden within the folds of life there are Tests, that only a Great Woman will know how to rise to; she hopes one day to rise to them herself. And then Lettie moves in as a lodger and her attitude is a breath of fresh air: scornful, quick-witted, realistic, Lettie swiftly dispenses with the cumbersome chains of Mrs Thornby’s draconian opinions, and the women form a tentative, mismatched but genuine friendship, one that will bring all sorts of Tests for Norah in its wake.

Out in her isolated manor, actress Rae Grainger waits for her baby to arrive, tended by the competent hands of her housekeeper, Mrs Givens, but tormented by the uncanny happenings in the old house, and her ignorance of childbirth. Her reading of 19th century novels does not seem to be enough to carry her through the experience. When she first hears about her waters breaking, she is disconcerted. ‘Rae sat down on the edge of the bed, trying to fit the idea of a big gush in with what she already knew. Had Mrs Dorrit protected her bedding? Had Jane Eyre had a big gush? Perhaps Mr Rochester had stood her a new mattress.’ In the meantime, Rae delights in the intricacies of Mrs Givens’ Cornish accent and begins to learn more about her past with her deceased twin sister, the local midwife, and their life running the former orphanage in which she finds herself staying.

This is a clever, neatly plotted novel whose strands all dovetail beautifully by the end. There’s also a line running through it about a dodgy doctor that perhaps could have been dispensed with, but it all comes together to form a vibrant picture of the desperate business giving birth used to be. I particularly enjoyed the style in which it is written. There are wonderful lines, like the moment when a young boy realises that his dead mother can’t be found in the stories she wrote: ‘Katherine Mansfield wasn’t in Bliss. She was a voice, she was a sharp pin holding reality still for him to look at… It was another complicated way of being absent.’ Or the moment when Lettie finally lays her hands on evidence of the doctor’s wrongdoing: ‘It felt so powerfully present in her pocket. A muscular trouble, its teeth so very sharp.’ The dialog is wonderful and I found the characters very endearing: Norah with her determination to meet life’s Tests, Lettie’s unapologetic eye on the main chance, Rae’s affectionate, generous personality. If this is that pitiful creature, women’s fiction, then bring it on. I would happily read many more books with as much wit and charm as this one.

p.s. I should mention that this is apparently a sequel to The Midwife’s Daughter. I didn’t realize this until I’d finished it, and it didn’t make any difference really to me.