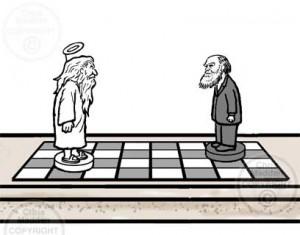

It shouldn’t surprise me any longer but somehow it still does. I’m talking about Darwin’s brilliance not simply as a naturalist but as one of the truly great intellects of all time. I was recently reminded of this while reading John Greene’s “Darwin and Religion” (1959), an article which I recommend for its nuanced treatment of the cosmological and metaphysical implications of Darwin’s theory.

Darwin himself was much vexed by these issues, and vacillated back and forth between the idea that evolution was mostly a matter of chance or subject to some law. Greene does a nice job of capturing the Necker cube nature of the issue:

“And so it went, around and around, in Darwin’s head — law and chance, chance and law. The difficulty was that, when nature was conceived as a law-bound system of matter in motion, chance was but the other side of a coin stamped law. In the old view of nature, chance and change had been the antitheses of design and permanence. The forms of the species were regarded as designed by God; varieties were products of time and circumstance, of chance, not in the sense of being uncaused or not subject to law, but in the sense of not being a part of the original plan of creation. Now, in the evolutionary view of nature, change was everywhere, and everything was either chance or law depending on how one chose to look at it.”

“I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae [wasps] with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice. Not believing this, I see no necessity in the belief that the eye was expressly designed. On the other hand, I cannot anyhow be contented to view this wonderful universe, and especially the nature of man, and to conclude that everything is the result of brute force. I am inclined to look at everything as resulting from designed laws, with the details, whether good or bad, left to the working out of what we may call chance. Not that this notion at all satisfies me. I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton. Let each man hope and believe what he can.”

Twenty-one years later (in an 1881 letter to William Graham), Darwin still hadn’t resolved the issue and expressed the kind of doubt which is the hallmark of a great thinker:

Darwin himself confessed to an “inward conviction” that the universe was not the result of chance. “But then,” he added, “with me the horrid doubt always arises whether the convictions of man’s mind, which has been developed from the mind of the lower animals, are of any value or at all trustworthy. Would any one trust in the convictions of a monkey’s mind, if there are any convictions in such a mind.”

(Greene 1959:724). This brings to mind one of my favorite Nietzsche aphorisms: “A very popular error: having the courage of one’s convictions; rather it is a matter of having the courage for an attack on one’s convictions.”