As a huge fan of the Museum of London and someone with an interest in, shall we say, the grittier side of London’s rich and chequered history, I can’t believe that it took me so long to finally pay my first visit to the Museum of London’s Docklands site, which inhabits a wonderful old building by the river in the shadow of Canary Wharf. I’m glad that I finally made the effort though and would definitely encourage all of you to go too, especially if you think your interests may at all coincide with my own.

I went early on a bright and breezy wintry Sunday morning in December (before heading off to see The Cure in Hammersmith – woo!) and very much enjoyed my stroll from the Canary Wharf station, through the deserted business district and across a bridge to the little isolated West India Quay, where the museum is located in an old warehouse alongside a series of bars and restaurants. It’s a delightful and fascinating locale that really sets the tone of the museum, for you arrive already fully conscious of the contrast between the picturesque wooden warehouses of the old docklands area and the gleaming tall office buildings that have sprung up as their successors. You’re conscious too of the presence of the river as it flows, gleaming and ribbon like beneath the bridge and past the very entrance to the museum itself.

The museum was opened in 2003 and is housed in an old sugar warehouse. The building itself is quite a contrast to the better known Museum of London by the Barbican, which has quite a sleek, modern vibe going on whereas its docklands counterpart is all about the mellow toned exposed brick, wooden floorboards and looks wise is much cosier and aesthetically very pleasing on the eye. It’s not precisely a beautiful museum but certainly a handsome one.

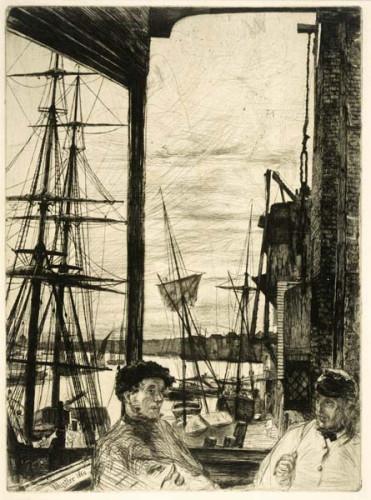

Rotherhithe, Whistler, 1860. Photo: Museum of London.

Although the museum appears very compact, it’s cleverly designed to make the most of its available space and is arranged on different floors with lots of well thought out displays and interesting little nooks and crannies to hold the interest of visitors. While its sister museum on the London Wall offers a broad look at the history of London from the most ancient times, as the name suggests, its docklands counterpart takes a close look at the history of the docks that have been such an important part of London, its daily life and economic expansion since Roman times. It is, in effect a microcosm of London itself as you will find all walks of life represented here, from aristocrats to wealthy merchants to the workers themselves and it makes for a fascinating and engrossing story.

The first part of the museum concentrates on the history of the port and river Thames from AD43 to the end of the sixteenth century and is full of fascinating exhibits – the most impressive of which, of course, is a 1:50 scale model of the Old London Bridge, which was apparently the first stone structure across the Thames. It’s a really fascinating and wonderful piece of work as one side shows how the bridge would have looked in around 1450, while the other, concealed behind a wall, shows how it would have appeared in its Tudor heyday and it really would have been a spectacular sight, except, of course, for the heads of traitors displayed there and so on.

Ooh and there’s also a display about the famous frost fairs that used to be held on the Thames when it froze solid enough to bear people’s weight. According to the Museum of London website ‘between 1309 and 1814, the Thames froze at least 23 times and on five of these occasions, the freeze was extensive enough to support the weight of festivities, and a Frost Fair was born. The Museum of London collection evidences five Fairs in 1683-4, 1716, 1739-40, 1789 and 1814.’

Gibbet, c1750-1800. Photo: Museum of London.

The next part looks at the how the London docks became a world center for trade between 1600 and 1800 with some really interesting displays about the building of the docks, ship building and so on. The best bit though was at the end, where there is an atmospheric reconstruction of a 1790s ‘legal quay’, or rather a wharve where ships would dock to unload their cargos and deal with customs and just as a reminder that piracy was a tremendous issue at this time – there’s also a scary looking iron gibbet around the corner, displayed to look like it is hanging by the Thames shore for full macabre effect.

After this I entered the London, Sugar and Slavery gallery, which is a permanent exhibition examining London’s involvement in the slave trade and which aims to make visitors ‘challenge long-held beliefs that abolition was initiated by politicians and be touched by the real objects, personal stories and vibrant art and music that have left their legacy on the capital today.’ Living in Bristol, I am often reminded of this completely shameful and dreadful period in history and find it very hard and upsetting to read about because I think it just defies all possible comprehension that anyone could ever think this was alright and an acceptable way of going about things. However, I made myself look at every object and read every single word in the exhibition and came away feeling very upset, very moved, very VERY angry but above all much more educated about the whole issue. I really think that this is something that everyone should see as it was so intelligently and thoughtfully presented, revealing just how far the prosperity of London at that time was linked to this shameful trade and what life was really like for the enslaved people.

Medal struck in 1814 to commemorate the 1807 abolition of the slave trade, 1807. Photo: Museum of London.

I had to take a moment to sit and think about what I had just read and seen after visiting this gallery but then proceeded downstairs to the displays about the prosperous, bustling nineteenth century docks and their relationship with the City as merchants, formerly despised for their ‘trade’ backgrounds, began to get very wealthy and influential indeed. I suppose that in a funny old way there’s still that link today as when people think of the London docklands nowadays, it is Canary Wharf and the ultra modern business areas that they think of – showing that the area still continues to be a bit of a money magnet even if the docks themselves are long gone. There are also displays about the new bridges, Brunel’s Thames tunnel between Wapping and Rotherhithe and some disgusting exhibits relating to the whaling trade, another reminder that London’s wealth and prosperity is at least partially built on cruelty and inhumane practices that we have now thankfully abandoned.

Next up was the bit of the museum that I had most been looking forward to – Sailortown, which the Museum of London describes as ‘a full size reconstruction of the dark, winding streets of Victorian Wapping. The gallery attempts to recreate the contemporary description of the area as “both foul and picturesque”. The area was a maze of streets, lanes and alleys. Its inhabitants catered to the needs of sailors of all nationalities alighting in London.

In 1852, the reverend Thomas Beames wrote of the area around the docks:

“Go there by day and every fourth man you meet is a sailor… Public houses abound in these localities… fitted up with everything which can draw sailors together… in a third class of house were professional thieves … they were evidently preying upon the drunken sailors whose ill luck had led them to places where they were little acquainted.”

Those brave enough to enter Sailortown will find an alehouse, sailors’ lodging house, chandlery, wild animal emporium, and much more.’

Peeping into a Victorian Christmas in Sailortown. Photo: my own (my camera was playing up so I have barely any photos!)

Unfortunately (for me!), I went on the Sunday before Christmas and the splendid Victorian Santa’s grotto was in situ in Sailortown, which must have been amazingly atmospheric for visiting children but less good for me as I couldn’t see much of it due to queueing parents and loads of abandoned pushchairs parked in front of everything. However, what I DID see was really amazingly atmospheric and gloomy as it literally actually is a short cobbled winding street lined with houses, shops and yards that give you a taste of what the area must have been like back then. I’ll definitely be going back soon to get a proper look at it, I think.

Although I would have to say that my taste definitely leans more towards the flouncy, shall we say, side of museums, I really enjoyed the gritty history that the Museum of London Docklands explores – there’s no pretty dresses on display but it is no less fascinating for that. I thoroughly enjoyed the area that explored the everyday life of Victorian dockers and their families, who lived in appalling conditions in the area’s many slums. Although previous displays had featured portraits of well upholstered, smug faced merchants, their wealth all came from exploiting the hard work of the grimy, underpaid and frankly poorly treated men who worked the docks. I was especially interested in this, I suppose, as my grandmother’s family lived in the area from the mid nineteenth century onwards and some of her relatives worked as clerks in the shipping offices, while some of ancestresses worked in the factories that also sprung up like mushrooms in the area.

Interior of a deprived home in Whitechapel, c1900. Photo: Museum of London.

Although the photos of the living conditions endured by the dockers’ families were grim indeed, I still found this to be a very interesting part of the museum and thoroughly enjoyed finding out more about the Princess Alice disaster, the 1889 dock strike and the building of Brunel’s Great Eastern, the sister ship of our own SS Great Britain which can be visited here in Bristol.

My grandmother’s family were still living in the area when WWII broke out so I was particularly fascinated by the gallery devoted to the docklands during the war, when the old docks were almost totally wiped out by German bombing during the Blitz. As the website explains: ‘The docks were an obvious target for Hitler’s air force and late in the afternoon of Saturday 7 September 1940, the Luftwaffe launched a massive daylight raid on London. Ninety consecutive night time raids followed. A collection of stunning paintings by William Ware (1915 – 1997) illustrate the intensity of the Blitz on London’s docks.

Other exhibits explore the Port’s role in the Dunkirk rescue, and secret projects such as construction of the Maunsell Forts; Pipe Line Under The Ocean and the huge breakwaters for the Mulberry Harbours. The gallery contains a life-size replica of a Port of London Authority (PLA) shelter constructed during the war. The PLA built two hundred of these shelters and they saved the lives of many people.

One of the Museum’s most treasured possessions is a flag that flew from the bow of one of the first landing crafts to reach France during the D-Day landings on 6th June 1944. It was found among the effects of George Sluman, a former waterman who was coxswain of the craft.’

Night Raid over London Docklands, Haines (a fireman who painted scenes from the Blitz but was sadly killed during a raid in 1944), 1941. Photo: Museum of London.

I knew, of course, all about the terrible and truly awe inspiring scale of the destruction in the docklands during that terrible time but was still completely shocked by what I saw and read. It really was absolutely beyond belief and incredible how brave people were in the face of such disaster. I found it all profoundly upsetting though – from Ware’s almost impressionistic paintings which look at first like abstract swirls of color and blackness but then gradually compose themselves into evocative images of firemen working in pitch blackness or bombs dropping on already burning warehouses to a display about the direct hit on South Hallsville School in Canning Town, where hundreds of sheltering civilians, already homeless and waiting to be bused to alternative accommodation, died.

I found myself standing for a long time in front of a panoramic photograph of the total destruction of a row of terraces in Silvertown, right next to the docks. This was especially moving to me because my grandmother’s family lived on one of those flattened streets – they had already been evacuated out to Woking but even so, it must have been shocking indeed. Rather conveniently, there is a special area at this point for quiet reflection, screened from the rest of the gallery by a wonderful stained glass screen designed to evoke the fires of the Blitz. I had to sit in there and have a bit of a cry as I felt a bit overwrought and overwhelmed by what I had seen – I couldn’t believe that I’d previously dismissed the Docklands museum as being of limited interest when actually it overflows with stories and history. It really is an astonishing place.

The rest of the galleries deal with the decline of the docks and their rebirth as a home for business, luxury apartments and upmarket shops. Although I really love the modern area as it is now and would probably live there in a heartbeat if I had move back to London, I have to admit that I felt a pang of sad nostalgia and regret for the gritty, grimy, busy, noisy old docks as they would have been a hundred years ago.

Flyer denouncing Rupert Murdoch during the industrial dispute of 1986, 1986. Photo: Museum of London.

I was completely exhausted by the time I’d finished my tour of the Docklands Museum – I wasn’t sure if I’d enjoy it to be honest as it deals with a more technical, grimier side to history than I perhaps am wont to take an interest in, but I was held absolutely gripped by the many displays, which teemed with multitudes of different stories. It certainly makes for a novel and fascinating view of London’s history, the ceremonial and royal side of which is, of course, so well known and is definitely somewhere that I would urge you to visit if you’re at all interested in the story of our capital city.

The Museum of London Docklands is located on the West India Quay by Canary Wharf and is open daily between 10am and 6pm. Entry is free. There’s a small shop, a really nice café and a rather awesome looking rum bar (with a bazillion different types of rum!) and restaurant in the converted warehouse next door. There’s also a special children’s area called Mudlarks in the museum, which I didn’t explore as I was on my own but it looked like a lot of fun with lots of interactive displays and toys and so on to play with. I’m planning to come back very soon with my family (I kept texting my husband with ‘YOU WOULD LOVE THIS MUSEUM. YOU HAVE TO COME HERE’ all the time that I was there!) so will see what it’s like then!

Jack Tar’s Drunken Frolic in Wapping, c1802-1819. Photo: Museum of London.

******

Set against the infamous Jack the Ripper murders of autumn 1888 and based on the author’s own family history, From Whitechapel is a dark and sumptuous tale of bittersweet love, friendship, loss and redemption and is available NOW from Amazon UK, Amazon US and Burning Eye.

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is available from Amazon UK and Amazon US and is CHEAP AS CHIPS as we like to say in dear old Blighty.

Follow me on Instagram.