by David Manthos / EcoWatch

Last week a video emerged of a giant fissure in the Northern Mexican desert, 3,300 feet long and up to 25 feet deep. Speculation centered at first around an earthquake, but the region is not known for seismic activity. I personally checked out the U.S. Geological Survey earthquake data because the Buena Vista Copper mine (the fourth largest in the world by output) is only about 150 miles north of the enormous crack, and earlier this month they spilled 40,000 cubic meters of sulphuric acid into two rivers during the worst spill in Mexico’s modern mining history. But I found no reports of tremors in the region and authorities were skeptical that this had anything to do with an earthquake.

Fast forward to Tuesday, Aug. 26, the Washington Post posted a story with this headline: Why no one should freak out about the giant crack that opened in the Mexico desert. The Post reports:

The chair of the geology department at the University of Sonora, in the northern Mexican state where this “topographic accident” emerged, said that the fissure was likely caused by sucking out groundwater for irrigation to the point the surface collapsed.

“This is no cause for alarm,” Inocente Guadalupe Espinoza Maldonado said. “These are normal manifestations of the destabilization of the ground.”

I’m sorry, no. These are not normal manifestations of natural activity, this the result of human activity run amok. Just because Cthulhu isn’t clambering out of the breach to wreak havoc on humankind does not mean we shouldn’t be alarmed by the fact we’ve sucked so much water out of the ground that the surface of the earth is collapsing.

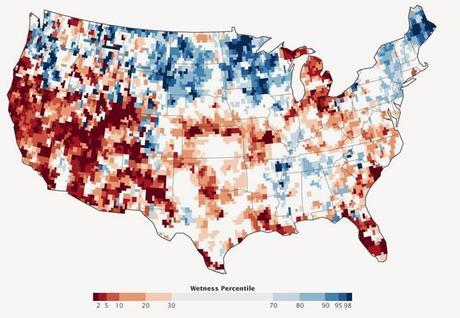

Barely a month ago NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory warned of ‘shocking’ groundwater losses in the Colorado River basin, a major watershed to the north of Sonora with similar climate and landuse. Using gravitational data from the satellite-based Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) instrument, scientists found “the basin lost nearly 53 million acre feet (65 cubic kilometers) of freshwater. That’s almost double the volume of the nation’s largest reservoir, Nevada’s Lake Mead. More than three-quarters of the total—about 41 million acre feet (50 cubic kilometers)—was from groundwater.”

Fast forward to Tuesday, Aug. 26, the Washington Post posted a story with this headline: Why no one should freak out about the giant crack that opened in the Mexico desert. The Post reports:

The chair of the geology department at the University of Sonora, in the northern Mexican state where this “topographic accident” emerged, said that the fissure was likely caused by sucking out groundwater for irrigation to the point the surface collapsed.

“This is no cause for alarm,” Inocente Guadalupe Espinoza Maldonado said. “These are normal manifestations of the destabilization of the ground.”

I’m sorry, no. These are not normal manifestations of natural activity, this the result of human activity run amok. Just because Cthulhu isn’t clambering out of the breach to wreak havoc on humankind does not mean we shouldn’t be alarmed by the fact we’ve sucked so much water out of the ground that the surface of the earth is collapsing.

Barely a month ago NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory warned of ‘shocking’ groundwater losses in the Colorado River basin, a major watershed to the north of Sonora with similar climate and landuse. Using gravitational data from the satellite-based Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) instrument, scientists found “the basin lost nearly 53 million acre feet (65 cubic kilometers) of freshwater. That’s almost double the volume of the nation’s largest reservoir, Nevada’s Lake Mead. More than three-quarters of the total—about 41 million acre feet (50 cubic kilometers)—was from groundwater.”

Groundwater reserves can take centuries to recharge, so industrial-scale extraction of water for big agriculture in the middle of the desert cannot continue forever. In the U.S., water managers are facing an uphill battle to control water use in the Colorado River Basin and from the Ogallala Aquifer which stretches from Texas to South Dakota. Factor in that hydraulic fracturing is permanently removing water from the hydrological cycle in some of the most drought-stressed regions of the West, and you have a serious problem.

To be clear, the entire southwestern U.S. is not necessarily about to fall in on itself all at once, but it is struggling to support large-scale agriculture, enormous demand for water from a revitalized onshore oil and gas industry, and a growing population. Maybe this chasm in the desert doesn’t herald the coming of Judgement Day, but perhaps we should be freaking out about our poor judgment.

This article was reposted with the permission of EcoWatch