- Academic.edu: https://www.academia.edu/37973310/Computation_in_Language_Process

- SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3300999

Contents

The Computational Mind, Losses and Gains 2 Words, Binding, and Conversation as Computation 4 What’s Computation? What’s Literary Computation? 7 Writing, Computation and, Well, Computation 8 The Computational Envelope of Language 11 Computation in Language: From speech input/output to writing, calculation, and electronic computers 13 Appendix 1: The importance of real-time processing of language 16 Appendix 2: A quick note on computing in the mind 17

Limits to the Computational Mind

For most of my career I have held that the human mind is, in some respect, computational in nature. In this I follow many others in the cognitive sciences and related disciplines. But, in what respect and to what extent computational? Chomsky took the view that much of language is syntax and that syntax is inherently computational. Though I am no longer sympathetic to Chomsky’s specific views on syntax, I was and remain sympathetic to the view that syntax is computational.

A decade before Chomsky began publishing his views on language Warren MuCulloch and Walter Pitts published “A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity” in which they argued:

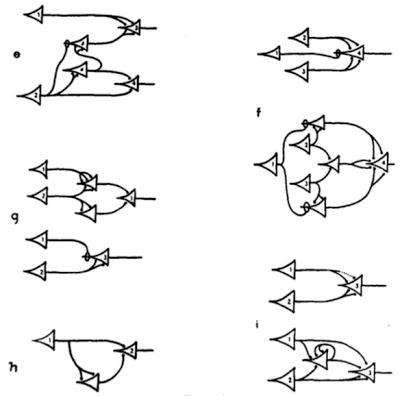

Because of the “all-or-none” character of nervous activity, neural events and the relations among them can be treated by means of propositional logic. It is found that the behavior of every net can be described in these terms, with the addition of more complicated logical means for nets containing circles; and that for any logical expression satisfying certain conditions, one can find a net behaving in the fashion it describes. It is shown that many particular choices among possible neurophysiological assumptions are equivalent, in the sense that for every net behaving under one assumption, there exists another net which behaves under the other and gives the same results, although perhaps not in the same time. Various applications of the calculus are discussed.The article contain illustrations that looked like highly stylized neurons:

That article helped set the stage for thinking that perhaps it was computation all they way down, or at least down to the level of individual neurons.

That view certainly has had and continues to have proponents. I can’t say that I’ve ever believed it; I’ve certainly never said so in print. And, as I learned about the nervous system, it seemed rather a bit too messy to operate on logical principles at its most basic level. In this working paper I explicitly reject the idea that it is computation all the way down and assert that language is the simplest human activity that involves computation. In my view linguistic computation serves as an input/output device for symbolic computation and thought.

What about those neurons then? If they’re not doing computation, what are they doing? That’s not my concern here. Whatever it is, it is something else. That something else may well be simulated by computational means, just as we simulate atomic explosions, the weather, and traffic patterns. The fact that we can simulate those phenomena computationally doesn’t imply that they are computational phenomena. And so it is with the nervous system. What is interesting about the nervous system, then, is that it evolved to the point where it could implement a computational process, speech, and that then became the partial basis for a shared cultural life different in kind and extent from animal cultures. But that is beyond the scope of this paper, which is limited to my reasoning about language.

* * * * *

Words, Binding, and Conversation as Computation – Here I argue that conversation is a computational process, that the binding of word forms to meanings (syntax) requires computation.

What’s Computation? What’s Literary Computation? – Continues the previous section and leads to the next.

Writing, computation and, well, computation – Here I talk about ordinary arithmetic calculation which is, of course, computation, and then say a word about algorithms.

The Computational Envelope of Language – In which I return to Saussure.

Computation in Language: From speech input/output to writing, calculation, and electronic computers – We can think of the mechanisms of speech as a Turning machine of limited power. The speech signal itself is analogous to the paper tape while the auditory system reads from that tape and the vocal system writes to it. The neortex contains the table of instructions and the state register.

Appendix 1: The importance of real-time processing of language – A abstract of a recent article about the information processing bottleneck that speech processing must deal with.

Appendix 2: A quick note on computing in the mind – An abstract of an article that David Hays and I published in 1988, “Principles and development of natural intelligence.” That article speaks to the issue of non-computational or pre-computational processes in the brain and places language in that context.