Roll back the clock 50,000 years and the world was a very different place. Up to 5 species of human were living side by side, including the Neanderthals and the hobbit, but now they’re all extinct (except us). That’s something I talk about a lot on this blog. Something I talk about less often is just how much the rest of the ecosystem has changed. Mammoths, woolly rhinos and dozens of other species of megafauna that lived alongside the Neanderthals had disappeared by around 10,000 years ago1. So where did all the mammoths go?

Were the captured by Hollywood for use in bad movies?

The term “megafauna” might conjure up impressive images of giants roaming the landscape, but really it basically means any animal larger than a deer. And that definition might make the animals seem a tad less impressive, but it makes these extinctions pretty mind-blowing. Some of the continents lost more than 95% of their megafauna2. Australia lost everything, apparently as a result of humans burning everything to the ground whilst hunting4. In some places it was a bit less severe, with Eurasia loosing just above 40% of its megafauna2

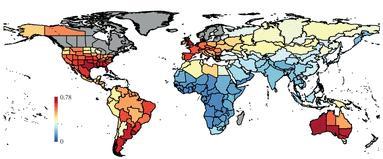

The percentage of megafauna that went extinct; with the darkness of the red meaning more exinction

These extinctions coincide with two important events. First, modern humans (us) began leaving Africa for the first time and spreading throughout the world. Shortly after this was the ice age (actually one of many, so should be called the “last glacial maximum”). So for quite a while now scientists have been arguing back and forth whether it was us or the ice age responsible for killing off the mammoths1.

As with almost anything in science, it seems the answer is “it’s complicated”. For a while a consensus has been emerging amongst researchers: in places where animals had encountered humans (or our relatives, like the Neanderthals) before they had adapted to us. This includes places like Africa and Eurasia. As such these extinctions were less severe, and those which did occur could likely be attributed to the environment. Meanwhile the places that had never seen a hairless upright ape before, such as the Americas and Australia, were hit hard by the arrival of humans and we wiped out a lot of the megafauna living there2.

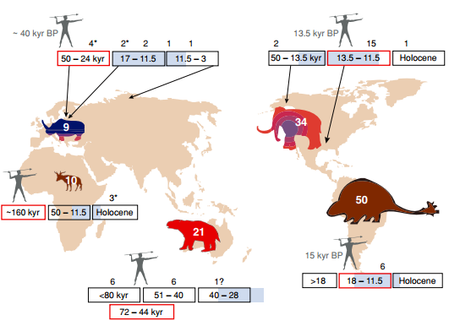

Bare with, this is perhaps the most difficult graph to explain. Basically the red box represents when modern humans arrived at various places, the blue bit represents climate change. The numbers above these time lines refer to when x number of species of megafauna went extinct. Finally, based on all this, the color of the picture of megafauna represents what can be blamed for the extinction. Red means its our fault, blue is the environment. The brown animal means “uncertain”

So where did all the mammoths go? In Europe they’d been living alongside Neanderthals for hundreds of thousands of years, so when we showed up they knew to avoid our spears. So they managed to survive for quite a bit longer, with some groups surviving until the pyramids were built. But climate change eventually finished them off. Meanwhile the mammoths in America didn’t know how to deal with humans; so were quickly finished off by the first people to arrive.

The end? Not quite, as research published earlier this summer challenges this nice little narrative. A team from Denmark began examining a whole range of extinction data from the period, not just restricting themselves to megafauna. This didn’t change the data too much, with Eurasia still having less extinction than America. However, this larger data set meant they could do a more rigorous analysis; analysing each country with data and checking to see if these extinctions are correlated with either the climate or human arrival3.

This investigation had two very interesting results. First: Uruguay has lost the most large mammals over the past hundred thousand years. Second: this research failed to find any correlation between the change in climate and the extinction of large mammals. Sure, in some places the extinction was less strongly correlated with the arrival of humans; but even in these places it wasn’t linked to the environment. In other words, it simply took longer for humans to wipe out the animals that were used to them (like European mammoths); not that the climate was responsible instead. Where the animals weren’t adapted to us, we could commit our megafauna genocide much quicker. There may have been some link with climate in Eurasia, but this was relatively minor. Humans are still to blame for most of it3.

I suspect the people behind the “humans only killed them some places” hypothesis (who really need a snappier title for their idea) will hit back at this research. There are a few flaws in the paper that lead me to think it isn’t the final word on the issue. Still, they present a compelling case and it’ll be tough for them to overturn it. So I guess everyone should start feeling bad that we killed all the mammoths.

And maybe you should bookmark this post, for the next time someone starts trying to argue about how people used to live in harmony with the environment and all that drivel.

References

- Barnosky, A.D., 2004. Assessing the Causes of Late Pleistocene Extinctions on the Continents. Science, 306, pp.70-75.

- Koch & Barnosky, 2006. Late Quaternary Extinctions: State of the Debate. Annual Review of Ecological Systems, 37, pp.215-250.

- Sandom, C., Faurby, S., Sandel, B., & Svenning, J. C. (2014). Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change.Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1787), 20133254.

- Rule S, Brook BW, Haberle SG, Turney CSM, Kershaw AP, Johnson CN. 2012 The aftermath of megafaunal extinction: ecosystem transformation in Pleistocene Australia. Science 335, 1483–1486.