The art of the “yo’ mama” joke is a sociological phenomenon dating back centuries. According to The Dozens: A History of Rap’s Mama by Elijah Wald, the tradition has its roots in ancient Africa and pre-Islamic Arab societies, with traces found in those parts of Europe such as Spain and France once conquered by the Moors. Even Shakespeare was fond of the word “whoreson.”

The art of the “yo’ mama” joke is a sociological phenomenon dating back centuries. According to The Dozens: A History of Rap’s Mama by Elijah Wald, the tradition has its roots in ancient Africa and pre-Islamic Arab societies, with traces found in those parts of Europe such as Spain and France once conquered by the Moors. Even Shakespeare was fond of the word “whoreson.”

In America, this oral tradition developed among African American culture as the “Dozens,” and was fueled in popularity by the blues. The blues itself is rife with paradox and the Dozens is no exception. It is at once an insult and an exhibit of deep affection and respect. While there is seemingly no more offensive gesture than to insult one’s mother, one would never allow such an insult unless there was already a shared respect for one’s opponent. If this were not so, every round of the Dozens would end in a fistfight. But the Dozens is not only about respect for your opponent, it is also about self-respect and personal ability. If you can go a full round of the Dozens with a worthy adversary, then you have accomplished something of worth. It keeps you razor sharp, quick witted, on your toes the way sparring does for a boxer.

The great jazz clarinet player, author, and drug dealer Mezz Mezzrow related the act of swapping insults back and forth in front of an audience to the great jazz tradition of “cutting heads,” where players jam with each other trying to outdo their opponent with intricate riffs and runs. But cutting heads isn’t about simply playing faster and louder; you don’t play over your opponent, you feed off each other, and the audience reaction. It is a joint performance as much as a demonstration of individual dexterity. Same with the Dozens.

The idea right smack in the middle of every cat’s mind all the time was this: he had to sharpen his wits every way he could, make himself smarter and keener, better able to handle himself, more hip. The hip language was one kind of verbal horseplay invented to do that…On The Corner the idea of a kind of mutual needling held sway, each guy spurring the other guy on to think faster and be more nimble-witted…cutting contests are just a musical version of the verbal duels.

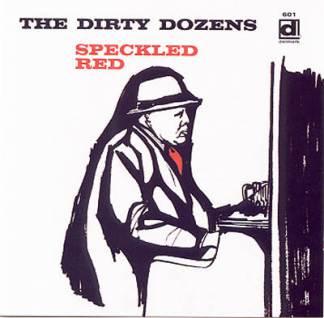

The natural rhythm of the process, much like the boxer’s jump rope (or the schoolgirl’s jump roping rhythmic rhymes, which can be equally obscene), lends itself inherently to song. Songs utilizing the Dozens date back at least to the pre-recorded vaudeville and minstrel show era; however, the first record to hurl the Dozens into the public consciousness was Speckled Red’s boogie piano recording of “The Dirty Dozen” in 1929.

Yonder go your mama going out across the field

Running and shaking like an automobile

I hollered at your mama and I told her to wait

She slipped away from me like a Cadillac EightNow she’s a running mistreater, robber and a cheater

Pappy is your cousin, slip you in the dozen

Your mama do the lordy-lord

Red’s recording is a sanitized version of a song that had been performed for years in various incarnations in the rough and tumble African American juke joints of the day. The lyrics heard in the clubs at the time were as graphic as anything heard today. The song was covered, with variation, by many of the era’s biggest blues stars including Kokomo Arnold, Leroy Carr and Memphis Minnie. Red himself would follow with “The Dirty Dozens No. 2,” “The Dirtier Dozens,” and the inevitable “The Dirtiest Dozens.” Memphis Minnie was one of the few female artists to reduce the Dozens to wax.

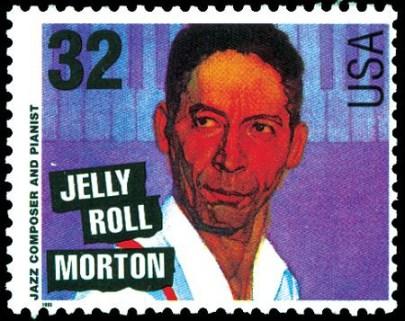

New Orleans brothel pianist Jelly Roll Morton, one of the founding fathers of Jazz, recorded his version for the Library of Congress in 1938. Morton’s recording, while still restrained, contains language considered highly offensive even by today’s lax standards of decency and includes the unlikely lyrical hook, “yo’ mammy don’t wear no drawers.”

WARNING: Although recorded for the Library of Congress in 1938, this record contains language that may be inappropriate for the workplace.

Bo Diddley made a series of trash talking proto-rap records where he traded insults with percussionist Jerome Green beginning with 1959’s “Say Man,” an unlikely hit single. Green’s maraca playing helped define the distinctive Bo Diddley sound and the chemistry between the two musicians in these recordings is irresistible. When Jerome cautions Bo that he might hurt his feelings with what he’s about to say about Bo’s girl, Bo retorts, “my feelings already hurt by being here with you.” Jerome ultimately wins this duel when Bo is unable to muster a comeback to Jerome’s claim that Bo looks like he has “been whooped with a ugly stick.”

Further proving that the Dozens is more a sign of affection and respect for one’s opponent rather than a source or reflection of hostility, Bo and Jerome returned the following year with “Say Man, Back Again,” appearing on 1960’s Have Guitar Will Travel album. Bo and Jerome begin casually, Bo mentioning that he saw Jerome’s girlfriend recently and that she is so nice she has everything a man would want: “hair on her chest, mustache, everything a man would want!” Jerome responds that Bo’s girl is so skinny she has to “tie some knots in her legs to make some knees.”

The B-side to the single of the Bo Diddley is a Gunslinger title track, released in December 1960, was another Bo and Jerome Dozens exercise entitled “Signifying Blues.” Although only a year or so after “Say Man,” the record begins not with insults about each others’ girlfriends, but instead with old man jokes. Bo points out that Jerome looks “ten days older than water,” and Jerome comes back without missing a beat that it looks like Bo’s “process took a recess.”

The obvious extension of the Dozens into the modern era is found in rap and hip hop. Adversarial rap battles provide a perfect platform for these verbal jousts; in fact they are born out of it. Early rap pioneers like Flavor Flav and Dr. Dre were notorious for chopping heads, their mutual respect showing behind the thinly veiled tough exterior of “yo’ mama” jokes.

Sometimes it seems the further we come as a society the more things come back around. When West Coast rappers The Pharcyde released their musical take on the Dozens – the 1992 single “Ya Mama” – the group left off some of the raunchiest lyrics in order to secure radio airplay, just as Speckled Red sanitized his recording of “The Dirty Dozens” over 60 years earlier.

When Wu-Tang Clan founding member Method Man released his debut solo album containing the song “Biscuits,” he brought Jelly Roll Morton’s 1938 recording full circle by beginning the first verse about somebody’s mother standing in a welfare line with Jelly Roll’s raunchy refrain, “yo’ mama don’t wear no drawers.”

Necessity truly is the mother of invention. Forcing the use of double entendre and symbolism to convey a crude thought forces the artist to flex a different muscle, to think outside of the box. Art, almost by definition, requires this struggle. At the same time there is something to be said for unapologetic authenticity, for art reflecting a culture or subculture’s actual words and experiences. Jelly Roll Morton’s unedited Library of Congress recordings may offend one sensibility, while the idea of an artist like Speckled Red being forced to tone down his original lyric in the studio may offend another. The world can be a rude and nasty place and it is important that music, especially the blues, occasionally reflect that. It is important these recordings be heard lest our history itself become sanitized. The rest is just signifying.