As Washington State’s Elwha River runs free, a habitat for fish and wildlife is restored.

by Michelle Nijhuis / National Geographic

The Elwha River flows into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, carrying sediment once trapped behind dams. The gradual release has rebuilt riverbanks and created estuary habitat for Dungeness crabs, clams, and other species. Photograph by Elaine Thompson, Associated Press. From National Geographic

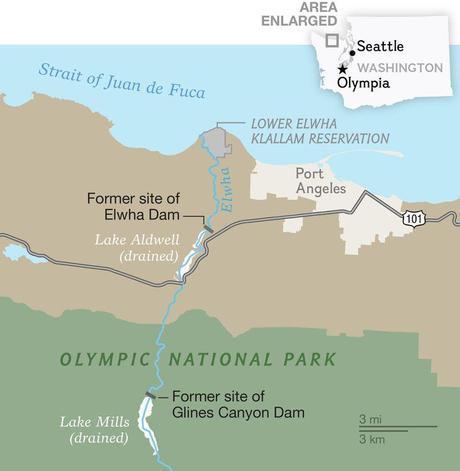

Today, on a remote stretch of the Elwha River in northwestern Washington state, a demolition crew hired by the National Park Service plans to detonate a battery of explosives within the remaining section of the Glines Canyon Dam. If all goes well, the blasts will destroy the last 30 feet of the 210-foot-high dam and will signal the culmination of the largest dam-removal project in the world.

In Asia, Africa, and South America, large hydroelectric dams are still being built, as they once were in the United States, to power economic development, with the added argument now that the electricity they provide is free of greenhouse gas emissions. But while the U.S. still benefits from the large dams it built in the 20th century, there’s a growing recognition that in some cases, at least, dambuilding went too far—and the Elwha River is a symbol of that.

The removal of the Glines Canyon Dam and the Elwha Dam, a smaller downstream dam, began in late 2011. Three years later, salmon are migrating past the former dam sites, trees and shrubs are sprouting in the drained reservoir beds, and sediment once trapped behind the dams is rebuilding beaches at the Elwha’s outlet to the sea. For many, the recovery is the realization of what once seemed a far-fetched fantasy.

“Thirty years ago, when I was in law school in the Pacific Northwest, removing the dams from the Elwha River was seen as a crazy, wild-eyed idea,” says Bob Irvin, president and CEO of the conservation group American Rivers. “Now dam removal is an accepted way to restore a river. It’s become a mainstream idea.”

(Related: “Spectacular Time-Lapse Video of Historic Dam Removal.”)

Before the Park There Was the River

The Elwha runs for 45 miles, from the Olympic Mountains to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and all but its final five miles lies within what is now Olympic National Park. Long before the park was established in 1938, the river was regionally famous as the richest salmon river on the Olympic Peninsula. For generations, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, whose members live at the mouth of the Elwha, depended on the river’s fish and shellfish for survival. But the peninsula was also famous for its massive trees, and in the early 1900s, the local timber industry needed power for its mills and its growing ranks of workers.

Fish were no match for finance, and the 108-foot-high Elwha Dam, located five miles upstream from the river’s outlet, started generating power in 1914. “There is no question but that the Elwha is harnessed at last and forever,” a local newspaper reporter crowed at the time. The larger Glines Canyon Dam, eight miles further upstream and inside what is now Olympic National Park, began operations in 1927.

NG MAPS. SOURCES: Washington State Department of Ecology; Washington State Department of Natural Resources

For almost half a century, the two dams were widely applauded for powering the growth of the peninsula and its primary industry. But the dams blocked salmon migration up the Elwha, devastating its fish and shellfish—and the livelihood of the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe. As the tribe slowly gained political power—it won federal recognition in 1968—it and other tribes began to protest the loss of the fishing rights promised to them by federal treaty in the mid-1800s. In 1979, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Washington tribes, including the Elwha Klallam, were entitled to half the salmon catch in the state.

With this court victory behind them, the tribes began to fight for the protection and restoration of salmon runs. In the mid-1980s, the Elwha Klallam and environmental groups started to push for dam removal in earnest, arguing that their environmental costs and safety risks outweighed their benefits—especially because the Olympic Peninsula had long since been connected to the regional power grid, and the dams now provided only a small fraction of the power used by its residents and mills. In 1992 Congress authorized federal purchase of the two dams on the Elwha from the timber companies that owned them and ordered a study of the idea of removing them.

Read the rest of the article at National Geographic