“We Poor People”

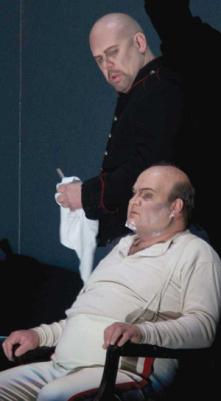

The Doctor and the Captain in Act III of Wozzeck

The Doctor and the Captain in Act III of Wozzeck

The Great War, as it was once called, served as the dividing line between the conventions of class-conscious Europeans and the introduction of modern sociological methods into fin de siècle thought. As an example, the resultant jolt that mechanized warfare brought to bear on the lives of the populace henceforth dispelled all pre-war notions of glory and honor in battle.

As previously indicated, 19th-century concepts of romanticism and morality, as they related to literature and art, were already on the wane and began to give way to more a nihilistic outlook overall. Cynicism and disillusionment grew rampant among those who survived the most catastrophic conflict Continental Europe had ever experienced.

While in literature the elevation of the poor and downtrodden to near reverence was hardly front-page material — Dickens, Hugo and Zola were a few of the outstanding authors whose novels had been preeminent before this period — it was Goya and his provocative Disasters of War etchings, Daumier with his powerful Rue Transnonain rendering, and Géricault via his monumental The Raft of the Medusa who had previouslyset the tone for polemically-charged artwork.

Not to be outdone, the advent of realism in opera (known as verismo), with such notable examples as Bizet’s Carmen, Puccini’s La Bohème, Charpentier’s Louise, Massenet’s La Navarraise, and d’Albert’s Tiefland, gave notice to audiences that attention must be paid to festering social issues and economic injustice.

This trend eventually brought forth new and artistically viable forms of protest, with expressionism one of the most striking. Having made its presence felt in late 19th to early 20th-century poetry and art, expressionism’s effect on music was elaborated on by German sociologist Theodor Adorno as the “literary ideal of the ‘scream.’” Every work of art, he wrote, was thus likely to be shocking or difficult to understand. Only through its “corrosive unacceptability” to the commercially-defined sensibilities of the middle class could new art hope to challenge dominant cultural assumptions (Source: New World Encyclopedia, August 24, 2012).

There is no other opera I know of that challenges our “dominant cultural assumptions” better than Alban Berg’s Wozzeck. Once scornfully referred to as “the twelve-tone Puccini,” Berg and his atonal compositions (to include the unfinished opera Lulu) have always occupied a shadowy corner of the standard repertoire. Accordingly, his works have earned the unique title of opéra noir (dark opera), an allusion to a type of drama where “the depiction of fear lies at the center.”

Dramatically speaking, we need only consider the much later Stephen Sondheim/Hugh Wheeler through-composed vehicle, Sweeney Todd, as a distant but equally perverted cousin.

Based on the exploits of a former soldier-turned-barber (again, the Sweeney Todd connection), the Willy Loman-like Wozzeck suffers a constant stream of mental anguish and physical abuse from his so-called betters. Unable to cope with his and his common-law wife, Marie’s impoverished status, Wozzeck lashes out impotently at his tormenters, to no effect.

In the opening scene, the hypercritical Captain rebukes Wozzeck for having had a child out of wedlock, thus questioning his moral makeup. Wozzeck counters with a profoundly moving observation that it is difficult for “Wir arme Leut” (“We poor people”) to have morals without money. At this retort, the Captain nearly chokes on his own vehemence. It’s a good thing he’s a fictional character. Who knows what he would say if he ever met up with Wozzeck’s promiscuous sister-in-arms, Lulu!

Wozzeck’s signature motto, “Wir arme Leut,” is repeated in the penultimate scene, after Marie’s brutal murder and his self-induced drowning have taken place, in what the late Saturday Review’s critic Irving Kolodin once praised as “a dirge for the collapsed world” of the protagonists, a “tensely, proudly beautiful and expressive” last interlude before the painfully poignant finale of the couple’s now-orphaned child playing on his hobbyhorse.

The themes of poverty, hopelessness and despair, spiced with a touch of the Grand Guignol, were explored in another brief work, Puccini’s one-act shocker Il Tabarro. This grimly realistic portrait of working-class Parisian life premiered as part of his Trittico (or Triptych) project at the Metropolitan Opera in December 1918, barely a month after armistice was declared.

Conceptually, Il Tabarro (“The Cloak”) has much in common with Wozzeck, in that both operas feature adulterous pairs in amoral circumstances, wretched social conditions, and overly violent episodes and/or conclusions. Puccini did not bask in this work’s unrelievedly gloomy company for long. His final lavish opus, Turandot, premiered at Milan’s La Scala in 1926, a year and eight months before Wozzeck made its mark in Berlin.

What a difference that year and eight months made! Why, to anyone’s ears there can be no question as to the sharp contrasts between these two composers’ approach to their subject: Puccini, the master melodist and experienced “man of the theater” extraordinaire; and Berg, a master of dissonance, as well as a doctor of musical expression and emotional upheaval.

John Rockwell of the New York Times described Berg as a gifted, “psychologically acute colorist” — but a “twelve-tone Puccini”? Hardly!

Welcome Back, Maestro Levine!

No other conductor has done more to turn the audaciousness of Berg’s Wozzeck into a palatable “twelve-tone” staple of the opera-going experience than Met maestro James Levine. Since first presiding over the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in a 1974 revival of this fabulous masterwork, Maestro Levine has conducted all but a handful of productions (he divided his Wozzeck duties with the British-born Jeffrey Tate during the 1984-85 season). Here, Levine’s experience with this work and how it should sound in the patently huge confines of the Met Opera auditorium proved invaluable.

The current revival, directed by Mark Lamos and designed by Robert Israel, premiered on February 10, 1997. “It was a dark production,” wrote veteran opera writer Garry Spector, “with splashes of color [red being the most prominent] and excellent use of shadow effects.” I heard the Saturday afternoon broadcast of March 22, with a cast headed by baritone Thomas Hampson in the title role, soprano Deborah Voigt as Marie, tenor Peter Hoare as the Captain, bass Clive Bayley as the Doctor, and tenors Simon O’Neill and Russell Thomas as the Drum Major and Andres, respectively.

This was Hampson’s first assumption of the difficult, laser-like role at the Met. His connection to Massenet’s romanticized Werther, the previous broadcast work, and Berg’s harried private Wozzeck is intriguing. Incredibly, Hampson has sung the rarely performed baritone version (arranged by the composer) of Werther on past occasions. Barring a few key changes and a transposed high note here and there — and given a singer of stature and charisma — it can be safely pulled off.

But how did Hampson do as the hallucinating “poor soldier” Wozzeck? With such illustrious Met predecessors as Hermann Uhde, Geraint Evans, José van Dam, Christian Boesch, Alan Held, and Mattias Goerne to contend with, Hampson raced through the ordeal with voice intact. He brought his own particular brand of emotional commitment and sterling musicianship to the part, along with his thorough preparation and a solidly-conceived incarnation of a man slipping ever so noticeably into madness.

Using his imposing height to his advantage, Hampson’s slender build is nowhere near Alan Held’s massively bulky form, bald pate and haunted visage. There’s something brutish about the character, but in a childlike, non-threatening way. Although possessed by inner demons, the best Wozzeck interpreters are fairly adept at evoking the audience’s sympathy. While Hampson proved a bit short in that department, his peerless tones nonetheless penetrated the heavy orchestration at crucial moments. The final denouement where Wozzeck wades into the lake to drown was gripping theater, thanks to Hampson’s noble efforts.

Deborah Voigt’s Marie, while not as taxing as her recent Wagner and Strauss assignments, was crisply acted, as well as firmly articulated. This is a most congenial role for Deborah, whose thinned out top notes in Die Walküre and Götterdämmerung have definitely seen better days. As Marie, she etched a sympathetic portrait of the whore with a heart of gold — for her child, that is — and an uncontrollable urge to be loved by the strutting Drum Major (trumpeting tenor Simon O’Neill). The famous bible-reading passage at the start of Act III was heartbreaking in its simplicity, as delivered by Voigt.

Peter Hoare’s Captain and Clive Bayley’s Doctor fit the general pattern set forth by Berg of two clueless and duplicitous souls convinced of their own infallibility, yet incapable (or unwilling) to notice Wozzeck’s physical and psychological deterioration. The other minor characters, as brief as their contributions were, each in turn contributed to the sum of the opera’s various parts.

This is a harrowing piece indeed, a disturbingly concentrated look at a sick mind trying to survive in a sick world. Wozzeck can take place at any time, and at any place. In that, it’s a timeless masterpiece of man’s inhumanity toward his fellow men. As an ensemble piece, Wozzeck is as intricate as anything in Mozart. And to think that at one time the opera was deemed unplayable (come to think of it, so were Strauss’ Salome and Elektra).

Much of the credit for the work’s staying power can be attributed to James Levine. His championing of this once inaccessible stage piece has enriched the modern repertoire and brought richness and diversity to the Met broadcasts.

Copyright © 2014 by Josmar F. Lopes