Two Peas in a Pod

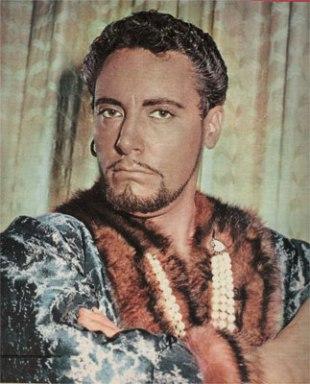

Placido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra (Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera)

Placido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra (Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera)

The subtitle of this post, “How the Mighty Have Fallen,” expresses not only the fate of Verdi’s title characters in Simon Boccanegra and Otello, but also the ultimate outcome of those who deign to hold public office.

Despite claims of only being a simple farmer and land owner, Verdi, that student of the affairs of state, was a shrewd observer of the body politic. He served as an unwilling member of the Italian Parliament when the fledgling republic had achieved its longed-for reunification. He was forced to deal with the absurd demands of the censors when faced with making radical changes to Rigoletto and Un Ballo in Maschera. He had also written about the difficulty of serving two masters in the first version of Boccanegra, as well as in the Judgment Scene from Aida and in the multiple revisions to Don Carlo, where public duty clashed with private anguish.

Today, we ourselves are bearing witness to similar wheeling and dealing, as a new administration begins to take hold via the age-old process of a peaceful transition of power. An endless parade of loyalists and appointees have come and gone, with each one vying for a piece of the coming administration’s pie. In this scenario, the main preoccupation appears to be the settling of old scores, along with the nursing of past grievances and perceived slights. To curry favor or gain the upper hand, politicians are prone to pit one against the other, a real-world Survivor contest in the timeless tradition of “may the best man win.”

These grievances and slights can serve as the modus operandi for any number of operatic plot points. Luckily for us, maestro Verdi has taken the drudgery out of the task. He has brought the problem to light by setting down for modern audiences the basis for the story lines of both Simon Boccanegra and Otello. Grazie, signore!

The two works, composed roughly 30 years apart (which takes into account Simon Boccanegra’s 1881 revival), are more alike than they seem to the untrained eye. Take the character of Paolo Albiani in Simon. A goldsmith by profession and a plebeian by birth, Paolo is an agitator as well as a political opportunist. In the Prologue, he is the person who proposes that Simon run for the office of Doge of Genoa. As his main supporter, Paolo expects to be handsomely rewarded for his efforts in guiding Boccanegra to the top. Unfortunately, the rivalry between the plebeians and patricians rages on after 25 years of struggle; while Simon, now older and wiser, continues to be looked upon as a pirate and usurper.

In the emotionally compelling Scene i of Act I, the aged Doge has come to inform Amelia Grimaldi that she is to be married to Paolo as a reward for his unwavering loyalty. She, on the other hand, is repelled by the money-grubbing Paolo who is only interested in her family’s wealth and status. When Amelia insists she is in love with another suitor (the fiery Gabriele Adorno), and especially when Boccanegra realizes that Amelia is his long-lost daughter Maria, he is obliged to renege on his promise to Paolo. Swearing vengeance, the now seething Paolo hatches a plan to kidnap Amelia and force Boccanegra’s hand, among other matters.

It is in the justly celebrated Council Chamber scene that the kidnapping plot is revealed and foiled. The antagonists face one another in judgment, hurling allegations of murder, inciting to riot, and various other misdeeds. Seemingly cornered and unable to escape his accusers, Paolo becomes the focus of the great ensemble that begins with Boccanegra’s outcry of “Fratricidi!” (“Fraticide!”), and soon after by his splendid oration whereby he quotes the poet Francesco Petrarca, aka Petrarch, pleading for peace and love between combatants: “E vo gridando: pace! E vo gridando: amor!”

The Act ends with Boccanegra ordering Paolo to pronounce a curse on the head of the man responsible for the uproar — in other words, on Paolo himself. Recoiling in abject horror, Paolo repeats the curse, “Sia maledetto!” (“Let him be accursed!”), which is picked up by the entire cast and chorus, then whispered twice more in unison. Paolo can only blurt out the word, “Orrore!” (“The horror!”), over the blasting of the orchestra. In the subsequent acts, Paolo executes on his promise to seek revenge by lacing Boccanegra’s drink with a slow-acting poison. What a guy!

No less a scoundrel is the duplicitous Iago of Verdi’s Otello. In Shakespeare, this villain’s motivation is basically his anger at being passed over for promotion. In Verdi and Boito’s reconfiguration of the play for the operatic stage, Iago is evil incarnate, as his magnificent “Credo” makes plain. “I believe in a cruel God,” he thunders forth near the start of the second act, “who has made me in His image and who in wrath I now worship!” Iago’s hatred of the Moor goes beyond his elevation of Cassio to the rank of captain. In fact, it borders on the pathological.

Paolo, too, has his “Iago moment,” coming as it does, coincidentally enough, at the opening of Act II of Simon Boccanegra. Next to Iago’s perfidy, however, Paolo is an outright amateur. Both men were written about extensively in the correspondence between the composer and his librettist Boito. “It is a pity,” Verdi insisted, “to have such powerful verses in the mouth of a common rogue … I have, therefore, decided that this one shall be no petty villain.” Boito stressed Paolo’s skill as a manipulator of public opinion, along with his willingness to switch sides to suit his own purpose. “Paolo should take an active part in the later uprising of the Guelphs to betray and dethrone the Doge,” he suggested to Verdi. “He will be caught, imprisoned and condemned to death. Thus we shall at last see the Doge put someone to death!”

Lest we overlook the composer’s sheer admiration of Shakespeare, we now turn to Verdi’s fascination with the fiendishly clever Iago: “His manner would be absent-minded, nonchalant, indifferent about everything, skeptical, bantering, and he would say both good and evil things lightly, as if he were thinking about something completely different from what he is saying, so that if anyone were trying to reprove him and say: ‘What you’re saying or what you’re doing is monstrous,’ he could perfectly well reply: ‘Really? I didn’t see it that way. Let’s say no more of it then!’ A fellow like that might deceive everybody, even his own wife, up to a point.”

Verdi was so taken with this character that he often referred to the opera as Iago, not Otello. This was partially due to the deference he paid to the late Gioachino Rossini, who had premiered his own version of Otello back in December 1816. Not wanting to take the thunder away from his much admired predecessor, he was mindful, too, that Rossini had set out to stage The Barber of Seville in juxtaposition to a prior version by Giovanni Paisiello. History records that Rossini’s original name for the work was Almaviva, ossia l’inutile precauzione (“Almaviva, or the Useless Precaution”). After the disastrous premiere and subsequent successful revivals, the title reverted back to The Barber of Seville. This convinced Verdi to think the matter over and keep Otello as the title of his piece. A wise move!

Is It Live or is It Memorex?

Both Simon Boccanegra and Otello have been recorded extensively, mostly in the modern age after the 1960s and 70s when complete albums of these works became readily accessible. Neither opera appeared to have had an especially strong following on 78’s, however, which points up the undeniable fact that even today excerpts from Boccanegra are extremely hard to come by. Certainly the LP era improved matters somewhat, as did the video and DVD/Blu-ray Disc period. Live performances of many rarely performed Verdi works are plentiful online and on-demand, as well as on YouTube.

If I were to recommend a particular recording or performance of either opus, I would have to say that a live 1939 Met Opera radio broadcast of Simon Boccanegra, featuring a sterling cast headed by Lawrence Tibbett, Elisabeth Rethberg, Giovanni Martinelli, Ezio Pinza, and Leonard Warren, conducted by Ettore Panizza, is high up on the must-have list. Tibbett spearheaded the Verdi revival at the Met of the 1930s. Here, this remarkable artist is at the top of his form, with a seamless legato, superb phrasing, peerless top notes, and that marvelous cello-like quality Tibbett was noted for. He and Rethberg make a marvelous father-daughter combo, as does the trumpet-like Martinelli (who was also an excellent Otello). Pinza is a model of what an Italian basso should sound like, and the young Warren was at the start of an illustrious career in Verdi. Included on this refurbished CD is a studio recording of the Council Chamber scene, with Rose Bampton replacing Rethberg, and Wilfred Pelletier on the podium. In either case, these are historic performances thrillingly captured for posterity.

For most opera buffs, Tito Gobbi is a name on everybody’s short list as one of the greatest Boccanegra and Iago interpreters. His RCA Victor recording of Otello with Jon Vickers and Leonie Rysanek is a model of its kind, due to the musicianship of conductor Tullio Serafin. Following close behind is Piero Cappuccilli whose snarl can be heard to fine effect as Iago in a live Arena di Verona video. The Otello is the wild Russian spinto Vladimir Atlantov.

Speaking of which, my favorite Moor performance comes from Mario Del Monaco, whose leonine stage presence, robust vocal output, and dynamic delivery of the text can be found in any number of live excerpts, including an astounding rendition of Otello’s grand entrance, “Esultate!” (“Exult!”). Del Monaco takes the difficult passage, “Dopo l’armi lo vinse l’uragano” (“To those who were left the storm has scattered”), in one long-held, drawn-out breath, comprising the usually omitted acciaccatura (or triplet) notation above the staff. He must have had iron filament for lungs!

Do live performances supersede their recorded counterparts? That all depends on the caliber of the artists involved. For the Met’s Boccanegra broadcast of April 9, we have Plácido Domingo in the lead, with Armenian diva Lianna Haroutounian as Amelia, veteran bass Ferruccio Furlanetto as Fiesco, Maltese tenor Joseph Calleja as Gabriele, American baritone Brian Mulligan as Paolo, and bass Richard Bernstein as Pietro. The ailing James Levine was back at the helm of the Met Orchestra, in the revival of a production by Giancarlo Del Monaco (the mighty tenor’s son), with sets and costumes by Michael Scott, and lighting design by Wayne Chouinard.

From the initial sound of things, I would say that Señor Domingo tried to give his considerable all to Simon. In the early portions, where the part stays comfortably in the middle of his range, Domingo was heard to best advantage. However as the opera progressed, the voice lost body and luster. In the all-important Council Chamber, it sounded disembodied from the rest. Where was the requisite authority, or the command of his forces implied in the opening lines to Boccanegra’s great speech, “Plebe! Patrizi! Popolo dalla feroce storia!” (“Plebeians! Patricians! People with a ferocious history!”)? The volume and fullness called for in this sequence was nowhere to be found. Boccanegra’s voice must soar above the fray. It must send shivers down his betrayer’s spine. He must dominate by virtue of his position as Doge. Here, it vanished into the woodwork, with no sign of the ever-present sea in the staging either, another of this production’s faults.

Gobbi, in His World of Italian Opera (published 1984 by Franklin Watts), describes Boccanegra as “a giant, both physically and in character. He cannot be performed by a small man … [T]he figure is of a tall, imposing man … It is not even a question of what is suitable for your voice, although naturally this is of first-class importance … It is the strength and nobility of the inner man which makes the effect, and he should be in harmony with his surroundings.” Domingo certainly has the height and physique du rôle, but at age 75 (at the time of this broadcast) the “strength and nobility of the inner man,” represented by what can be transmitted via the voice, can no longer hold its own. This has given short shrift to a part Verdi himself considered to be “a thousand times more difficult” than Rigoletto.

I have spoken about this distortion to the composer’s carefully calculated effects on a number of occasions. Domingo’s attempts to do justice to the great Verdi baritone parts continue to do his favorite composer a disservice. Now, I know that Plácido Domingo began his career as a baritone, later changing over to tenor and back again to baritone. I wrote about this transition a few years ago in connection to his appearance as the elder Germont in La Traviata (see the following link for details: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2013/04/14/salad-bowl-italian-opera-style-continues-with-la-traviata/). But his soft-grained, streamlined variation on the manly, baritonal timbre has short-changed audiences expecting a more viral, penetrating interpretation.

At full tilt, that sound can be the most visceral imaginable! Give me a Leonard Warren, an Ettore Bastianini, a Cornell MacNeil, a Robert Merrill, or a Sherrill Milnes any day of the week. I’ll even take a Renato Bruson, a Giuseppe Taddei, or even a Leo Nucci when pressed hard for examples. All started and ended up as baritones, nothing more and nothing less.

For a change of pace, Chilean dramatic tenor Ramón Vinay, a noteworthy Otello, Samson, Tristan, and Siegmund in his day, began as a baritone. He switched over to tenor in the 1940s and 50s, but reverted to bass-baritone in the early 1960s to assume such parts as Telramund in Lohengrin, Bartolo in The Barber of Seville, and Scarpia in Tosca. There’s even a snippet of Vinay as His Moorship’s Ancient, Iago, with Del Monaco’s tremendously exciting Otello (documented on YouTube) in a 1962 broadcast from the Dallas Civic Opera of the “Si, pel ciel” Vengeance Duet, conducted by Nicola Rescigno. Vinay kept that rich, dark timbre from his baritone days, as evidenced in the above excerpt. Domingo, regrettably, has not.

Cast from Strength

The other members of the cast showed their mettle. Ferruccio Furlanetto’s rich-voiced Jacopo Fiesco was an absolute joy to listen to. He fulfilled every nuance and requirement — even down to the low F called for in the aria, “Il lacerato spirito.” He dominated at every turn, his booming basso falling pleasantly on the ear, as did that of the mellifluous sounding Joseph Calleja in a memorable portrayal of the hot-headed Gabriele Adorno. Calleja’s been able to tame his quicksilver vibrato to the point that he can concentrate on characterization. I enjoyed his “Sento avvampar nell’anima” solo, with its rapid articulations indicative of Gabriele’s shifting states of emotion. Soprano Lianna Haroutounian matched him in vocal quality, with some fluid outpourings in the Council Chamber scene amid her dramatic pronouncements. Her lovely Act I scena was meltingly sung, as were her duets with both Gabriele and Boccanegra.

The only other downside, in my view, was — surprise, surprise — the inconsistent conducting of maestro James Levine. At times, Levine lost track of the forward momentum of this piece, which is deserving of a steadier hand in order to makes its subtle effects felt. His wasn’t necessarily a “bad” performance, just not up to his usual high standards. His finest moments were during the Council Chamber scene, which was to be expected. Verdi poured his heart and soul into this newly minted sequence, one that supplanted an earlier one that proved entirely inadequate. It may remind listeners of the big concertato that closes Act III of Otello. As well it should, since the 1881 revision of Boccanegra preceded the later work by only six years.

Getting to the new Bartlett Sher/Es Devlin production of Otello, heard on April 23rd, the listening audience was in for more than its fair share of surprises. To begin with, this was another in a long line of tiresome “barebones” production values. By that, I mean shifting glass-mirrored panels (or window panes — more like “pains,” if you get my drift) taking the place of actual scenery and sets. We were treated to more of that dispiriting “same old, same old” look that most productions have encompassed of late. The mirrored effect of all those sliding panels finally came into its own in Act IV, with Desdemona’s bedroom. And the opening storm scene, one of Verdi’s most elaborate episodes, featured some interesting cloud formations via digital software.

Otherwise, listeners heard a radio tribute in celebration of the four hundredth birthday and death of William Shakespeare (!). Nice, but what about the singers? Well, starting things off were American baritone Jeff Mattsey as Montano, Siberian tenor Alexey Dolgov as Cassio, Serbian baritone Željko Lučić as Iago, and Texan Chad Shelton as Roderigo, followed by squally Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko as Otello, and a pristine-sounding, movingly sung Desdemona by Abkhazian-Russian soprano Hibla Gerzmova, with mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano as Emilia, baritone Tyler Duncan as the Herald, and low-volume bass James Morris as Lodovico. The conductor was Hungarian-born Ádám Fischer.

The most consistent of the above artists happened to be maestro Fischer, who started Otello off with a (literal) bang in an utterly involving storm scene of manic turbulence and excitement, helped along by the wonderful Met Opera Chorus under Donald Palumbo. This tidal wave of sonic splendor dissipated somewhat at the appearance of an under-powered, under-the-weather Antonenko, which highlighted another problem with this production: Otello wasn’t even in “blackface,” to use the politically incorrect term. More to the point, Otello is supposed to be a Moor, a black African man in an all-white Venetian society, serving at that society’s whim to rule, in their name, as a governor on the island of Cypress.

I’ve been impressed in the recent past by his assumption of the Russian repertoire, in particular a very fine Dimitri in Stephen Wadworth’s staging of Boris Godunov from 2010, and some notable Puccini assignments, including Ramerrez in a Swedish production of La Fanciulla del West by director Christof Loy. The tenor is only in his early 40s, but he’s managed to develop a nagging wobble that has marred many of his performances.

More problematic was Antonenko’s inability to find his comfort zone with Otello’s daunting tessitura. I’ve heard my share of disastrous assumptions in years past, as well as an unnerving one by the barrel-chested Richard Cassilly. I have listened to enough broadcasts and recordings of the work, including several live transmissions and actual stage presentations, to form my own opinions about how Otello should be handled. And I instinctively know when a voice has the stamina and thrust to acquit itself favorably in the part. I’ve also been privy to the best of the best: Zenatello, Martinelli, Vinay, Del Monaco, Vickers, McCracken, Cossutta, Domingo, Cura, et al. But never have I heard a more wobbly, more tonally inferior, more dramatically inert performance than the one I experienced with Antonenko.

To be fair, even though no announcement of his disposition was forthcoming, I sensed trouble ahead, from the moment he opened his mouth. The love duet with Gerzmova’s beautifully inflected soprano, came off better than expected. And Antonenko’s Act II wasn’t all that bad, thanks largely to his Iago, the ubiquitous Lučić. For all his skills and ability in this repertoire, Lučić does not sound like your standard Verdi baritone. He hits all the right notes, holds on to those high ones with vigor and heft, and even injects an equivalent degree of dramatic urgency to whatever he imparts. This is what may have saved the broadcast from complete and utter ruin.

That, plus an intriguing last-minute substitution by debuting Italian tenor Francesco Anile as Otello, put this radio transmission on the radar. After the Act III ensemble, in which Otello flings his poor wife to the ground and practically accuses her of having an illicit affair with his former lieutenant, the disgraced Cassio, Antonenko , at the line, “L’anima mia, ti maledica!” (“Wife of my bosom, I curse thee!”), lost his voice. So little was left of his vocal apparatus that he barely got the words out. No wonder the chorus ran off to shouts of “Orror!” (in an echo and reversal of Paolo’s infamous cry at the Act I curtain to Simon Boccanegra).

A quick switcheroo took place behind the curtains, as Antonenko’s cover was moved into position for Act IV. Overlooking one of the balconies nearest the stage, Anile was dressed in jeans, sneakers, and T-shirt, but with a black cape covering his form, while Antonenko mimed the role onstage. Right on cue, Anile delivered a most welcome Italianate rendition of the last act of Verdi’s masterpiece with an ideal Shakespearean flourish.

Now HERE was a sound I had not heard in many a season. The Met was indeed fortunate to have engaged the services of this veteran artist, who has sung Otello and most of the Italian repertoire in his native Italy (he hails from the Reggio Calabria area) and abroad. In September 2016, Anile sang in the revitalized New York City Opera production of Pagliacci, via the principal role of Canio — a performance that generated glowing reviews.

We remain hopeful that a Met Opera star in the making may have been born that afternoon. Let’s hope, too, that another star tenor, i.e., Aleksandrs Antonenko, can recover from this ill-fated episode to re-emerge as the talented individual he no doubt is.

The mighty may yet recover from their fall …

Copyright © 2016 by Josmar F. Lopes