Book review by George S.: Hank Janson (pronounced Yanson) was, to the embarrassment of the respectable, Britain’s best-selling author in the late forties and early fifties. This excellent book describes the career of Stephen Frances, the man behind the pseudonym, and gives a very full account of the attempts of various authorities to censor the sexually suggestive tough-guy novels that appeared under the Janson name.

Born in 1917, Stephen Frances, the creator of Hank Janson, had a hard and impoverished upbringing in South London. He left school at fourteen and worked as a shipping clerk, but was more interested in left-wing politics. He wanted to go and fight in Spain, but never made it. During the Second World War he was a conscientious objector on political grounds.

As the war progressed, he drifted into the printing and publishing business, and became one of those socialists who, when they have become enterprising, are slightly embarrassed to find that they have become capitalists.

Among the books he published was a novel based on his own tough early life – with embellishments. Its hero, unlike Frances, does get to Spain to fight for the International Brigade.

One day in cc Frances was in possession of a quantiry of paper – a valuable property in those days of rationing. He had no manuscript to hand to make quick use of, so supplied one himself, and Hank Janson was born.

In a while his publishing firm ran into financial difficulties, so Frances quit the business, and became a full-time author, producing Janson books at an impressive rate.

He profited from an opportunity created by the government’s ban on American imports. The American pulp detective magazines that had been very popular in Britain could no longer be imported. (In Cambridge, the austere philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who was a great fan of these mags, had to ask friends in America to post him the locally unavailable copies of Street and Smith’s Detective Magazine.) British writers saw a gap in the market, and writers like Peter Cheyney and James Hadley Chase took advantage of it. Writers like Cheyney copied the Americans, and Stephen Frances (aka Janson) copied Cheyney.

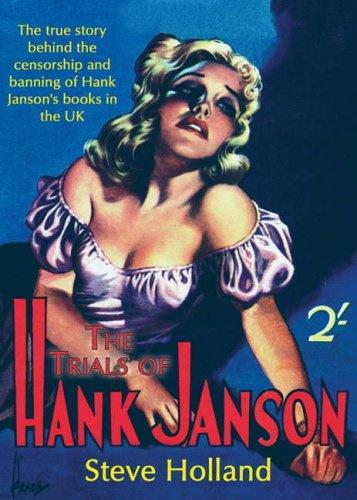

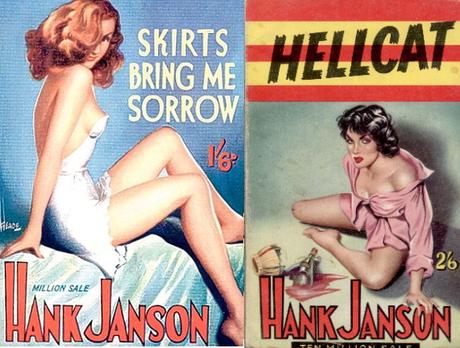

The books were written in the first person (like Cheyney’s novels), and the writer’s pseudonym was also the name of the its hard-boiled hero. Sentences are short and the language is punchy. There is a fair amount of sex and violence, but the texts rarely seem to have lived up to the suggestive garishness of their covers, mostly designed by Reginald Hoade.

By the early fifties, the books were selling in their millions. A sign of their popularity was the recording by Anne Shelton, one of Britain’s most popular singers, of Hank Janson Blues:

‘Cause Hank is a guy

A wonderful guy

He’s tough, but he’s kind you see.

He has the breaks, He’s got what it takes,

But he takes no time out for me!

So I’ll stick around and wait for my chance,

Guess I’ve got nothing to lose!

But till this guy’s in the mood for romance,

I’ve got the Hank Janson blues,

I’ve got the Hank Janson blues! ( )

The song was banned by the BBC.

The publishers plausibly claimed sales in the millions for the books and in time attracted the notice of those who set themselves up as the nation’s moral guardians. Local watch committees set the police raiding bookshops and newsagents and confiscating copies. Most of the booksellers targeted were small operators who were content to lose the confiscated stock rather than face the expense and risk of a trial in court (which could have resulted in heavy fines or imprisonment). The obscenity laws in the fifties were fairly arbitrary, and judgments depended on the attitudes of local magistrates. Steve Holland explains:

The Hank Janson novel The Jane with Green Eyes, published in July 1950, had twenty-two destruction orders issued against it in 1951, but was declared to be not obscene by magistrates in Stockton-on-Tees in July of that year. The same book was successfully prosecuted and found to be obscene in Darwen eighteen months later.

In 1954, Hank Janson’s publishers challenged a confiscation, and had their day in court. The prosecuting counsel was Mervyn Griffith-Jones, who specialised in obscenity cases, and is best remembered for his role in the 1960 Lady Chatterley trial (and especially for asking the jury: ‘Is it a book that you would have lying around in your own house? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?’) Steve Holland gives a detailed account of the trial, and points out that Griffith-Jones was inaccurate in his lurid description of the prosecuted books, and claimed that ‘Hank Janson’ described tortures that he actually left to the reader’s imagination. The members of the jury were given very little time to actually inspect the books. The Jury were strongly influenced towards a Guilty verdict, which they provided, and the two publishers in the dock were each fined two thousand pounds and sentenced to six months imprisonment. After the trial, a question was asked in parliament about the fact that the prosecuted titles had been on sale to servicemen in the NAAFI.

Stephen Frances was not among those prosecuted at this trial, but when he came back to England, he was prepared to defend his work. The trial collapsed in confusion, however. But then the whole law of obscenity at this time was confused. Swindon magistrates were roundly mocked for ordering the destruction of copies of the sometimes bawdy medieval classic, The Decameron, while letting Janson’s Don’t Mourn Me, Toots go free. In 1959 the Obscene Publications Act provided new criteria for prosecution, and clarified the situation to some extent.

The golden age of Hank Janson died with the 1950s. Frances, despite his enormous sales, had made remarkably little money from the books. He sold the pseudonym to a firm that kept on publishing Hank Janson novels without him, and himself wrote pulp fiction in various genres (crime, science-fiction, erotica) for various publishers under various names. He died in 1989, leaving behind an uncompleted autobiography, which he called The Obscenity of Hank Janson, Steve Holland has drawn extensively on the manuscript of this in his excellent account of Janson’s life and works.

This book gives an insight into a particular time in British publishing, when the ban in American imports opened an opportunity for British pastiches of the hard-boiled genre, and when the paperback market was still unformed. Penguin dominated at the respectable end, but small firms could stake their claims to sales, and sell their goods via bookshops, libraries and newsagents. From my childhood in the fifties I remember that our local newsagent offered a small shelf of books. There were westerns, I think, and other crime novels, but what I remember most vividly are the row of flashy and lurid Hank Janson covers.

As the fifties progressed, big publishing firms moved into the paperback market, and the more piratical outfits slowly disappeared. And by the end of the decade, Ian Fleming was offering more sophisticated sex and violence, and even nastier torture scenes than Hnak Janson ever did, but with a great deal more class. Times change.