Recently I got round to watching last year’s Ruby Sparks on DVD. I’d been looking forward to watching this film for some time because it is a mediation on what would happen if we could create our perfect partner. The film was everything I’d hoped for. However, when I gushed about it on facebook, several people said they had felt let down by the ending. Here I want to present my take on the film, and to explain why I think the ending needed to be the way it was.

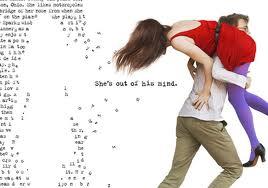

Ruby Sparks

In the film an isolated writer (Calvin Weir-Fields) has writer’s block having published one highly successful book when he was pretty young. His therapist encourages him to write a brief account of a positive encounter with another person. He invents a scenario where he meets his perfect girlfriend in the park. Soon he is writing more and more about her because he enjoys imagining her so much. He describes her to his therapist:

Calvin: Ruby Sparks. Twenty-six years old. Raised in Dayton, Ohio.

Dr. Rosenthal: Why Dayton?

Calvin: Sounds romantic. Ruby’s first crushes were Humphrey Bogart and John Lennon. She cried the day she found out they were already dead. Ruby got kicked out of high school for sleeping with her art teacher… or maybe her Spanish teacher. I haven’t decided yet. Ruby can’t drive. She doesn’t own a computer. She hates her middle name, which is Tiffany. She always, always roots for the underdog. She’s complicated. That’s what I like best about her. Ruby’s not so good at life sometimes. She forgets to open bills or cash checks and… Her last boyfriend was 49. The one before that was an alcoholic. She can feel a change coming. She’s looking for it.

Dr. Rosenthal: Looking for what?

Calvin: Something new.

Spoiler alert: Don’t read on if you want to watch the movie without knowing what happens.

During the time that he is writing about Ruby, Calvin starts to find bits of women’s clothing around his house and things in his bathroom cabinet that don’t belong to him. Then one day he returns home to find that Ruby exists and is living with him. She believes that everything from their first encounter to her moving in with him has actually happened.

After initial confusion Calvin is delighted and throws himself into a real relationship with Ruby. The two enjoy a perfect honeymoon period captured in a movie montage of dancing, beaches and running around town. But things start to sour when Calvin introduces Ruby to his family who she loves whilst he finds them problematic. He begins to become grumpy with the very things that he created Ruby to be.

Calvin’s brother, Harry, has suggested that Calvin should continue writing about Ruby in order to make her into whatever he wants. However, even when she is getting on his nerves Calvin refuses to do this. Then Ruby begins to pull away for some independence: wanting to start a job, hanging out with her friends, and deciding to spend one night a week back at her own flat to give them some space. Calvin panics and returns to his typewriter. He writes that Ruby was sad whenever she wasn’t with Calvin. Ruby then becomes needy and tearful, unable to be parted from Calvin for a moment. Calvin writes that Ruby was effervescently happy all of the time, in order to try to keep her with him but not so demanding. This also backfires because constant happiness is hard to take, and because it is clear that Ruby isn’t choosing to be with Calvin at this point, so he writes her back to normal.

The couple return to bickering and fighting when Ruby doesn’t do what Calvin wants her to do. There is also the sense that the constant changes have taken a toll on Ruby emotionally. At a party she is left alone and flirts with Calvin’s agent. At this point Calvin explodes and tells her what she is, forcing her to do things by typing them out as she stands in front of him. Finally he stops and she runs to her room. He is struck by the horror of what he has become and leaves all of the pages that he has ever written about Ruby outside her room with a final line saying that Ruby is no longer bound by the past and that as she leaves the house she is set free.

The following morning Ruby has disappeared and Calvin is left alone to mourn. Eventually he pulls himself together and buys a computer instead of a typewriter. This was a relief to me because the main problem that I had with the film was understanding how somebody could write a perfect first draft into a typewriter! Calvin writes the story of his time with Ruby, anonymised, and it is a great success.

At the end of the film – which my facebook friends found so problematic – Calvin bumps into Ruby in the park. She is reading his new book but clearly she has forgotten everything that happened due to being set free. They have some banter similar to the first time that they met and it seems that Calvin has been given a second chance at the relationship, but this time having learnt his lessons in love.

There are probably many different readings of this film, and perhaps the way in which you read it affects how you view the ending. Two readings particularly struck me: we could understand the film as an exploration of gender in relationships (and wider society), and/or we could understand it as an examination of how people relate to each other more broadly. We don’t have to discard one reading in order to accept the other as both are possible through the same situations, and indeed the way we relate to each other is generally infused with gender. However, the latter reading perhaps invites a more sympathetic understanding of Calvin: and one in which we might be more likely to wish him the redemption he receives in the final scene.

Deconstructing the manic pixie dream girl

Under a gendered reading we could see Ruby Sparks as an explicit deconstruction of the manic pixie dream girl trope in fiction. In this common romantic plot, a man’s rather empty emotionless life is given meaning when he meets a wacky, quirky woman whose wild and childlike ways help him to learn to love and to free himself from his self-imposed constraints.

Clearly this trope was on the authors’ minds when they were writing the film. When Calvin first describes the woman that he is writing about to his brother, Harry, Harry replies: ‘quirky, messy women whose problems only make them endearing are not real.’

Not only does the film expose the lack of realism in the manic pixie dream girl trope, it also directly challenges the various specificaally problematic aspects of this trope, particularly the way in which it infantilises women and the approach it takes to mental health.

When Calvin tries to justify Ruby to his brother saying ‘she’s a person’, Harry responds ‘you haven’t written a person, okay? You’ve written a girl’. There are echoes here of Beauvoir’s theories that men are regarded as human beings whilst women are seen as being something other than that, and that part of this othering involves infantalising women such that femininity is bound up with being childlike and non-threatening. Interestingly this all relates to freedom. Men are expected to embrace their freedom – and the responsibilities which go with it – in life, whilst women are dissuaded from doing this and encouraged rather to be ‘for-others’, making themselves into the dutiful daughter or the perfect partner, for example, and remaining in a childlike state where they do not embrace their freedom. It is interesting that Ruby explicitly links the freedom and infantilisation towards the end of the film when she responds to Calvin’s attempts to control her saying ‘I’m not your child!’ Calvin’s assumptions in this matter are clear given that he isn’t even willing for Ruby to have a job in a coffee shop or to go out with friends because these things would be for her rather than for him. There is also something particularly sinister in Harry’s argument that Calvin should keep writing Ruby after she appears: ‘for men everywhere, you’ve got to take advantage of this’.

The continued popularity of the manic pixie dream girl trope in indie movies of the last decade such as Garden State or Elizabethtown suggests that the ideal of the woman who is childlike and non-threatening and exists ‘for-others’ is alive and well, and Ruby Sparks does well to reveal it and to criticize it. Calvin’s misogyny is clear in the way in which he describes his previous girlfriend as a ‘heartless slut’. However bad her behavior may have been, the term ‘slut’ is bound up with the sexual double standard, suggesting that women are a different species to be judged on different terms to men, and ‘heartless’ also suggests that women should properly be emotional and nurturing and that it is problematic for them to move away from such stereotypes.

The manic pixie dream girl trope also echoes wider societal representations of women as ‘mad rather than bad’. Because women cannot be seen as having freedom or responsibility, if they behave in ways which are difficult or different this tends to be regarded as a sign of mental ill-health rather than as morally problematic or criminal. Statistics on the numbers of women and men diagnosed with mental illnesses, and convicted of crimes, support the suggestion that there is still a tendency to view women as mad and men as bad (although there are certainly shifts in this over time, and intersections with race, class and other factors have an influence).

In addition, the manic pixie dream girl has to walk a fine tightrope between being mad enough but not too mad, akin to the tightrope of the sexual double standard where she has to be sexual enough but not a slut. When Ruby becomes properly depressed, and then manic, after Calvin has written her those ways, it is clearly unacceptable and reason enough for him to make further attempts at radical changes. There is an interesting commentary here on women’s mental health in (heterosexual) relationships. From The Yellow Wallpaper, through writing on body image, authors have argued that women’s attempts to make themselves into something ‘for-others’ in general, and ‘for-men’ in particular, can take a huge toll on their well-being.

If we read Ruby Sparks as a criticism of the manic pixie dream girl trope in general, and the differential and hierarchical treatment of men and women in wider society in particular, then perhaps we can understand why my facebook friends found the ending so appalling. Why should a man who objectified a woman – trying to shape her into exactly what he wanted her to be, infantalising her, messing with her mental health, denying her freedom, and dictating her sexuality – be offered a second chance?

One way to answer this is to point to the impossibility of stepping outside of culture. I think Ruby Sparks challenges the viewer (of whatever gender) to ask themselves whether they have honestly ever treated a woman in this kind of way. If they can’t answer that they haven’t, then perhaps they need to ask the same sympathy for Calvin as they would want for themselves.

Going further than this, perhaps we can – in some ways – regard Calvin as all of us in all relationships, not just as a man with a woman in this particular relationship.

Treating each other as things

Something that Beauvoir and Sartre agreed upon is our tendency is to treat other people as objects for ourselves in relationships. Terry Pratchett nicely captures this when his character, Granny Weatherwax, says ‘sin, young man, is when you treat people as things, including yourself, that’s what sin is’. It may be sin, but it is a sin that we’re all guilty of pretty much every day of our lives. And it is perhaps particularly prevalent in romantic relationships when we are thrust into close proximity with another person on a regular basis, when we get to know them better than we do other people in our lives, and when we come to be particularly dependent on them for various aspects of our material and emotional well-being (such as our confidence being linked to their approval, or our ability to do things being linked to their income and/or responses to our behaviour).

In a way we could be impressed by quite how long Calvin waits until he starts to try to change Ruby. It is only when he really fears losing her that he returns to his typewriter. It is worth asking ourselves whether we wouldn’t be tempted to use such a mechanism if we had it available to us, and in what ways we do something similar but with less awareness of it. Women’s and men’s magazines and self-help style books are consistent in their attempts to help us to figure out and play the ‘opposite sex’ in order to get them to do what we want them to do, sexually or otherwise. The ‘beauty and the beast’ myth of a woman being able to change a man plays out in relationships all the time, when people attempt to trick, cajole or nag their partner into self-promotion, diets or better domestic habits. It is important to admit to ourselves the temptation to make little tweaks and alterations to a partner, at the same time as holding them back from changing in directions that we are not comfortable with, or feel threatened by. And even if we don’t actually do anything, do we still give a clear message to our partner that we are not really okay with who and how they are with a sigh, a gesture or a hurt expression?

Ruby Sparks nicely captures some of the problems with this way of behaving, beyond the – hopefully obvious – ethical implications. Calvin wants his free-living Calvin-loving manic pixie dream girl, but he doesn’t want her too free, or too manic, or too dependent on him. Altering one aspect of her which he doesn’t like often results in altering other parts of her that he really did like. And the realities of living with another person are that there will inevitably be times when you don’t mesh. It is therefore difficult when Ruby is either dependent or independent, sad or happy, passive or active.

For me one of the most horrific moments in Ruby Sparks is not when Calvin is explicitly re-writing Ruby, but a much more mundane moment. She is singing a lovey-dovey made up song, off-key, in the kitchen. He is lying on the couch. He looks up and snaps something like ‘I’m trying to read’. This attempt, by Calvin, to make Ruby into a thing for himself, is all the more disturbing perhaps because it is impossible for the viewer not to see a mirror of themselves in the scenario.

As Sartre and Weatherwax both point out, there is a temptation to make ourselves into things for others which is just as powerful (and just as much of a sin?) as the temptation to make others into things for ourselves. Perhaps one of the main things that Calvin wants from Ruby is for somebody to love him for the way he is. And perhaps his own dislike of the way he is was responsible for his previous isolation and for his seeking help through therapy.

Again this path is fraught with problems. If we can find (or, in Calvin’s case, create) a partner who loves, respects and is fascinated by, us as we are then we will likely be in constant fear of losing this. Thus we try to mold ourselves into what we think they want us to be and/or the sides of ourselves that we were displaying early in the relationship when they fell for us. This is unsustainable so we end up failing and hating ourselves or resenting our partner for constraining our freedom in this way. Or perhaps, like the rewritten Ruby, our partner continues to see us as marvelous whatever we do and we eventually come to distrust them and to be frustrated with this because we know – ourselves – that it is not true and we are really an imperfect flawed human. As Calvin wearily puts it ‘she wasn’t happy. So I made her happy… and now she’s like this all the time.

It is often harder to see how self-objectification hurts anyone other than ourselves, but it does. Insisting that another person sees us in a certain way is unkind, as is letting them feel responsible for our well-being, guilty for hurting us when we suffer, and therefore constrained in their own freedom.

Why we need a happy ending: Calvin is us

If I’m honest with myself it’s quite probable that they gave Ruby Sparks a happy ending because they originally had a more bleak and realistic ending which didn’t go down well with Hollywood focus groups. If I’m super honest with myself perhaps I’m just a sucker for a happy ending myself and all this attempt to justify it is part of my own desire to believe that there is something possible beyond the Sartrean view that ‘hell is other people’ because we are doomed to keep objectifying each others and ourselves.

Despite having a more nuanced view of relationships than Sartre – recognising the tangle of ways in which gender and other aspects are messed up with our overall human tendency to objectify – Beauvoir was also more optimistic than Sartre about relationships, influencing his own later work which also began to see a way out of objectification.

Beauvoir thought that mutual relationships were possible and that in these people would embrace each other’s freedom, and their own, and support each other in their projects in life.

We could see the end of Ruby Sparks as a move towards this mode of relating. Calvin sees the horror of what he has done to Ruby and he sets her free. Her well-being now means more to him than continuing his relationship with her, which is perhaps the ultimate sign of embracing of another person’s freedom. He is willing to go through grief and pain in order to stop treating somebody in this way. He has seen the suffering that regarding another person as a thing causes.

I wish Calvin a happy ending with Ruby because I think that we are all Calvin. Whoever we are we will have treated other people – probably the other people who we love the most – in similar ways to the ways in which Calvin treats Ruby. And if we look closely we can also see the problems in the ways in which Calvin treats himself: thinking that he is not okay and needing somebody else to prove to him that he is. We’ve probably all done that too.

So saying that Calvin is undeserving of a happy ending is tantamount to saying that we are not either and, whilst this may indeed be true, it also seems rather harsh.

Like Beauvoir I believe that mutual relationships are possible. They are not something we can ever achieve 24/7. We are bound to slip into objectification all the time and need to avoid beating ourselves up for it because expecting constant perfection is another way of treating ourselves as things. But mutual relationships are something to aspire to: an ethics to commit to in our relations with others and with ourselves. We can admit to ourselves, and others, when we have fallen into objectification. We can increase our awareness of the impact of this, and the ways in which our various forms of self- and other- objectification are impacted by power imbalances of gender, race, class, age and so many other aspects. And we can keep committing to doing something different: recognising and valuing the freedom of ourselves – and others – equally, and aiming for relationships of mutual support.