Wagner, Mozart, Verdi & Puccini (arcanoartists.com)

When people think of “opera,” they usually picture a fat, overweight soprano in Viking headgear, screaming at the top of her lungs and singing in some incomprehensible language about who-knows-what. That’s the general impression.

But does anyone ever go beyond the stereotypes? Beyond the yelling and screaming and what-have-you, to discover what makes opera and opera singing the art forms they are?

Without getting too deep into the “what, when, how and why” of opera, let’s begin by discussing the “who” — i.e., four of opera’s best known composers: Mozart, Verdi, Wagner and Puccini, the cornerstones of the operatic repertoire. But does talking about them make our task any easier? And how does one go about describing these formidable giants and their works?

Well, one way is to do that is to provide some context. In this case, some stormy weather, as if we haven’t had enough of that lately! What I mean is, we can start with a blast of ocean breezes, the taste of salt water and the briny deep, the sense that a wave is about to hit the side of your vessel and wash you and your whole crew overboard… Does that sound inviting?

Believe it or not, those are exactly the qualities to be found in the Overture to The Flying Dutchman conducted by James Levine with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra (11:44): (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rNg07c0Mocg).

Whew! You could just feel the force of the sea in that one. This and many other works you’ve encountered in films, TV and animated cartoons are all of an operatic nature – which is to say this particular musical theme was originally part of a full-length opera, in this instance one written by that most unlikeable genius of the German stage, Richard Wagner, one of opera’s greatest hit-makers.

And that’s the theme of my post for today: we’re going to take a brief look at the lives and works of several of these hit-makers. The Fab Four of Opera, as I like to call them. We’ll try and find out what made them tick, as if such a thing were possible. Needless to say, it can be safely stated that without these utterly unique individuals, the operatic repertoire as we know it would be thin indeed. So, to keep the oceanic metaphor going, let’s plunge right in!

Oh Wolfie, oh Wolfie

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (www.last.fm)

The earliest of our fabulous hit-makers (born on January 27, 1756) was also the most prolific: Mozart, or, to use his full baptismal designation, Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart. But no matter what his real name was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart does have a nice ring to it. If you cut out his first and last names and use only the “Amadeus” portion he added later in life, you wind up with a fairly good title for a hit play.

Yes, I must confess – and I say this with all due respect to British playwright, Sir Peter Shaffer, for his wonderful theatrical contributions throughout the years – that hit play of his, Amadeus, has done more damage to the memory of one of Western music’s most talented artist/musicians than anything I could ever dream up on my own.

It’s done quite a lot of good as well, in that it succeeded in making Herr Mozart a household word. Despite the numerous fallacies and false implications the play and the subsequent 1984 film version (directed by Milos Forman and written by Mr. Shaffer) conspired to perpetrate on unsuspecting audiences, they did get some things right: Mozart’s jovial nature for one, along with his absolute disregard for money matters, his fun-loving ways, his notorious potty-mouth, his clashes with his father Leopold, his flighty, devil-may-care attitude about love and life, and so on.

They also got a lot of things wrong – dead wrong, in fact. The most glaring piece of misinformation was the long-held belief that Mozart was secretly poisoned by his arch-rival, Italian composer Antonio Salieri (1750-1825) – a neat and tidy dramatic device, for certain, but one not borne out by the facts.

Antonio Salieri (culturacolectiva.com)

Recent scholarship has revealed that “Wolfie,” who died in 1791 at the age of 35, may have been the victim of kidney failure, followed by rheumatic fever and/or uremic poisoning – take your pick. Part of the problem with trying to come up with an exact cause of death is the simple fact that Mozart was buried in a pauper’s grave; ergo his remains have never been examined or exhumed.

Not satisfied with that, some scholars have gone so far as to compile a list of 125 other possible explanations for Mozart’s early departure from this world – all of them deriving from a whole host of supposed physiological ailments and social diseases. But not once in the entire historical record has poison ever been mentioned as the main culprit in the composer’s demise. Yet, in spite of all evidence to the contrary, romantic (and unsubstantiated) rumors of his untimely passing have continued to survive to this day.

Another of those dubious elements that plagued both the play and the movie were Mozart’s struggles to produce an operatic hit. We know, for instance, that he played fast and loose with his finances; that he constantly borrowed funds from wealthy patrons in order to make ends meet; and that he was terribly slow at paying back his debts, which is fine as far as they go.

But to suggest that Mozart’s comic masterpiece, The Abduction from the Seraglio, had “too many notes,” as Austrian Emperor Joseph II seemed to imply; or that his remarkable opera Don Giovanni, one of the two or three greatest works for the stage ever created, was his “darkest, blackest work yet”; or that his most agreeable bedroom farce, The Marriage of Figaro, was a long and boring flop, is totally out of bounds and too troubling to overlook.

Still, one has to admit that all this manufactured drama does make for some intriguing flights of fancy, so who am I to complain? And, as the old saying goes, “You can’t argue with success.” If the play and the movie have succeeded in drawing new audiences to Mozart’s sublime art, so be it. It’s all for the best anyway.

Let’s listen now to one of the composer’s best, an excerpt from the opera Die Zauberflöte, or as it’s known in the English-speaking world, The Magic Flute. This performance was taped at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. It’s one of the Met’s most celebrated productions, sung in an excellent English translation (attributed to poet J.D. McClatchy) by an international cast. It was directed and designed by Julie Taymor, a past veteran of stage and screen, and no stranger to musical theater, who was responsible for Broadway’s The Lion King a few years back and, at last notice, was associated with the troubled stage musical Spider-Man: Turn off the Dark.

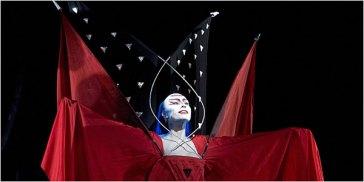

Erika Miklosa as the Queen of the Night (Cory Weaver / Met Opera)

We’ll hear the Queen of the Night’s lively vengeance aria from Act Two. The plot of this work is too convoluted to get into. It has something to do with the forces of good and evil, with a touch of Freemasonry thrown in for good measure. The role of the Queen of the Night is sung by Hungarian coloratura Erika Miklosa (3:47): (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QWUOeWHvn3k)

That’s a fiendishly difficult piece to bring off. This particular production, a truncated version of Mozart’s much longer work, includes lots of spoken dialogue, which is not as unusual as it sounds for opera. Beethoven’s Fidelio and Bizet’s Carmen are prime examples of this type of hybrid work, one that incorporates both spoken and sung passages. In this country, Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd and A Little Night Music can be included in that distinguished “company” – no pun intended.

(End of Part One)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes