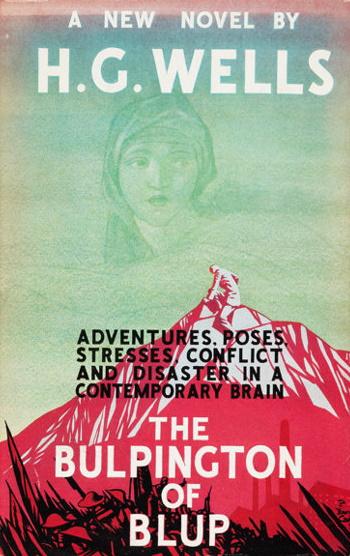

Book Review by George S: 1932 is a long time after H.G. Wells's brilliant scientific fables of the 1890s, and over the intervening period he had developed into a pretty bad novelist. But of The Bulpington of Blup, one can say that, while it is indeed not a good novel, it is not as dreary as Jane and Peter, or one or two others.

In The Bulpington of Blup, Wells is attacking a caricature of the people who disagree with him. The book's non-hero is Theodore Bulpington - Wells is doing the tiresome trick of giving a ponderous and ridiculous name to someone he disapproves of. Bulpington is a fantasist. When very young he imagines a heroic alter ego for himself, the Bulpington of Blup -always valiant, always dashing, always right. To him this imaginary self is as real as the actual one, and with unblushing cognitive dissonance, he continues to believe that this fantasy figure is the real him, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

Theodore is born into a literary family. His father is the sort of man of letters who writes clever articles, but never gets down to the real historical research that he says is his life's work. This literary man is disturbed by reading the 1901 novel, The Inheritors by Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Hueffer., which imagines a race of the future:

a race clear-sighted, eminently practical, incredible; with no ideals, prejudices, or remorse; with no feeling for art and no reverence for life; free from any ethical tradition; callous to pain, weakness. suffering and death, as if they had been invulnerable and immortal.

from The Inheritors, Chapter One.

These people represent a scientific future, of which the Bulpingtons are terrified.

Despite this fear of a scientific future, , the Bulpington family is friendly with the Broxteds, who are all scientists, and therefore sane, and grounded in reality. The early chapters of the book have a great deal of Arts versus Science debate, all very much loaded towards Scientists (because the spokespersons for the arts are all either fakes or fools). Theodore, a poseur, develops reactionary political views, and becomes Anglo-Catholic in religion. It's obvious that Wells considers this the silliest of all religious creeds.

When Theodore becomes a young man, he is torn between two women. Sophisticated Rachel takes him to bed, but he still manages to convince himself of the purity of his love for Margaret Broxted, the scientist's daughter.

Comes the Great War and his imaginary self is fighting with exemplary courage, while the actual him doesn't get around to enlisting. He tells others that he has been rejected for medical reasons - and comes to believe his own story.

At this stage of the book, a reader will come to recognise that this is one of those novels which creates an unsatisfactory character and then uses the War to test him and prove that he is wanting. Theodore predictably fails every test that Wells sets up for him. When he finally does enlist (just in time to avoid conscription) he is a useless soldier (except in his imagination). He does not fit in with the soldiers in his platoon (who think him a fool for believing newspaper rhetoric). He lets a rich uncle wangle him a cushy job out of the lines. When that falls through, he applies for a commission.

Leading his men in the trenches, he is unprepared for the reality of war, and suffers mentally; he sees visions of huge black dogs out in No-Man's-Land; In battle, he runs away in a funk. Luckily he is assigned to a sympathetic, if scornful medic:

The diagnosis of such cases as Theodore's varied with the M.O. concerned. Sometimes the diagnosis led straight to the bleak and sorrowful firing party at dawn. But there were understanding and merciful men among those M.O.s, there were some who never passed a man on to such a fate, and it was Theodore's luck to encounter a doctor of that new school and not a martinet of the old.

But the M.O. cannot help speculating;

"I wonder if it would be better if all chaps like you were shot," he considered. "Would it improve the race? Are you obliged to be what you are? Or did you miss something or get something wrong as you grew up?"

The medic chooses not to report the circumstances of Theodore's breakdown, and so he is able to go off, pretending to himself that he has had a good war.

After the war he pursues Margaret Broxted again, but she has become engaged to someone else. Unable to accept, or even to believe, this, he sends her abusive and distressing letters, with the result that her fiancé comes round to tell him to stop. The fiancé is Laverock, the medic who had treated him after his running away. This man sees through Theodore, and is scornful of 'the lies you tell about yourself' and 'your self-glorification'. He says:

When I looked you over at Mirville I was half-minded to let you be shot. I asked myself [...] is this breed worthwhile?

Wells is using the language of eugenics to label Theodore a type not worthy to live. I've read quite a few shot-at-dawn narratives, but have never read one quite so unsympathetic to the man who runs away in panic.

The two men begin a fight, and Theodore of course loses. Wells won't let him win anything.

After this, Theodore goes away to Paris, where he calls himself Captain Blup-Bulpington, and becomes a literary man.

He starts a 'brilliantly aggressive' magazine that combines literary modernism with reactionary politics. The magazine uses eccentric punctuation and typography, 'and always there were five or six pages of undulating designs by a new genius who wrote a sort of universal prose, symbolic prose, entirely without words.' This sounds like transition, the ultra-modernist literary magazine based in Paris, which published fragments of Joyce's Finnegans Wake, and the very strange experiments of its editor, Eugene Jolas. Bulpington's magazine combines literary modernism with social conservatism, and prints 'briskly controversial papers by catholic divines'; this suggests a resemblance to T.S. Eliot's magazine, The Criterion.

T.S. Eliot comes in for something of a kicking in the later parts of this novel. Maybe this is not surprising. Eliot was prone to deliver judgments on Wells like this one, from a book review:

Mr. Wells has not an historical mind; he has a prodigious gift of historical imagination, [...] but this is quite a different gift from the understanding of history. That requires a degree of culture, civilization and maturity which Mr. Wells does not possess.

from a 1927 book review in The Criterion.

Wells depicts the Anglo-Catholic Bulpington contentedly enjoying one of Eliot's Anglican pamphlets:

He had found no Punch on the bookstall but [...] took a witty little booklet by Mr T.S. Eliot on the Lambeth Conference from his valise and read it with appreciation. It was impossible to resist Eliot's implication that all's well with the Anglican world. The very way he mocked at it made one feel how real and important it still was and was going to be. Real and important things were going on being real and important for ever. Bishops were bishops in saecula saeculorum, and God was God.

Eliot feeds Bulpington's self-satisfied fantasies, but there is more than this. Wells also presents Eliot as part of a dangerous political tradition. He has Bulpington burble about:

One vast conspiracy! To destroy the social order. Thank God, we have people alive to it! Nesta Webster, a great invigilator - laughed at, at the time. Now T.S. Eliot. You should read T.S. Eliot. One of the Master Minds of our age. A great influence. Restrained, fastidious, and yet a Leader. The Young adore him. He has taken over the message of Nesta. Made it acceptable. Dignified it.

Nesta Webster was a vicious Anti-Semite who wrote books proving that the Jews were behind Bolshevism, Freemasonry and the Illuminati. (If you really want to, you can read her horrible book Secret Societies and Subversive Movements free online from Project Gutenberg). Her work is absolutely crackpot conspiracy theory. To associate Eliot with this is pretty savage.

The novel ends with Bulpington finding his apotheosis at a boozy dinner where he spins fantastical versions of his life story for a couple of very silly and easily-impressed old ladies. He goes home believing that essentially all his stories are true. He has learned nothing.

So H.G. Wells takes four hundred and eight pages to set up an idiot and then knock him down. Parts of the book are entertaining, and I did want to keep reading - but I was reading more as a historian interested in attitudes than as the eager devourer of a novel. It's a pretty bad book, actually.

Several of our group read much better novels by Wells - the early science fiction books especially are still definitely worth reading. Maybe by 1932 he had become too famous to be told by his publisher to take his manuscript back and rewrite it less self-indulgently.